Un pioniere dei segreti quantistici della materia / A pioneer of quantum secrets of matter

Un pioniere dei segreti quantistici della materia / A pioneer of quantum secrets of matter

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

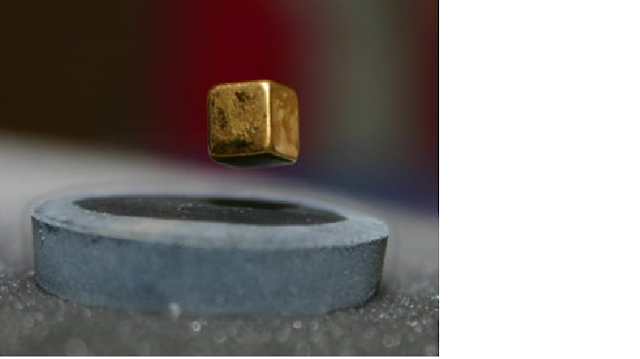

Un'immagine iconica per il fenomeno di superconduzione: un magnete resta

sospeso sopra un campione di materiale superconduttore raffreddato con

azoto liquido a -200 °C. (Credit: Peter Nussbaumer/Wikimedia Commons) /

An iconic image

for the superconducting phenomenon: a magnet remains suspended over a

sample of superconducting material cooled with liquid nitrogen at -200 °

C.

Gilbert Lonzarich per oltre quarant'anni è stato un pioniere nello

studio della fisica della materia condensata. Le sue idee, accolte

inizialmente con diffidenza, sono diventate la base per gli studi degli

stati esotici che si producono quando gli effetti delle temperature e

delle pressioni estreme incrociano quelli della meccanica quantistica.

Nel 1989, un intervento chirurgico per un distacco di retina lasciò

Gilbert Lonzarich cieco per un mese. Piuttosto che sentirsi scosso o

depresso, il fisico della materia condensata dell'Università di

Cambridge, nel Regno Unito, colse l'occasione per invitare i suoi

studenti laureati a casa per condividere con loro quanto fosse

entusiasmante adattarsi alla vita senza vista. Il modo in cui Lonzarich

ha abbracciato questa esperienza cattura perfettamente il suo approccio

alla vita, dice Andrew Mackenzie, all'epoca uno degli studenti e ora

direttore del Max-Planck-Institut per la fisica chimica dei solidi di

Dresda, in Germania. "Gil è una delle persone più positive che abbia mai

incontrato: prova interesse per tutto", dice.

Per oltre quarant'anni, ottimismo e curiosità hanno portato Lonzarich a

studiare i materiali in modi che non si pensavano possibili. In una

serie di esperimenti pionieristici degli anni novanta, il suo gruppo ha

dimostrato che portare composti magnetici a pressioni estreme e vicino

allo zero assoluto può far sì che alcuni di essi conducano elettricità

senza resistenza. Questo andava contro il pensiero convenzionale,

secondo cui magnetismo e superconduttività non avrebbero mai potuto

mescolarsi. "Era come se oggi si parlasse di trovare alieni o qualcosa

del genere", spiega Malte Grosche, suo collega a Cambridge.

Quel lavoro ha mostrato ai fisici un nuovo modo di dare la caccia ai

superconduttori, che sono il cuore di tecnologie come gli scanner per la

risonanza magnetica e gli acceleratori di particelle. Negli ultimi

anni, ha offerto una possibile spiegazione al fatto che alcuni materiali

rimangono superconduttori a temperature molto più alte dello zero

assoluto, il che potrebbe aprire la strada allo sviluppo di dispositivi

efficienti e economici che super-conducono a temperatura ambiente.

Ma gli

esperimenti hanno avuto un impatto che va ben oltre la

superconduttività. Il metodo di Lonzarich di sottoporre i materiali a

condizioni estreme è diventato una ricetta generale per scoprire nuovi

stati della materia. In tutto il mondo, i fisici ora usano questo

approccio per studiare una gamma di materiali in cui le interazioni

collettive degli elettroni possono dare origine a comportamenti

inusuali. Alcuni di questi fenomeni potrebbero rivoluzionare i computer.

La ricerca di Lonzarich può essere leggendaria nella sua comunità, ma l'umiltà e la generosità del fisico sono ciò che lo fanno apprezzare ai suoi colleghi. È famosa la sua inconsapevolezza dello scorrere del tempo; una conversazione casuale con Lonzarich può facilmente portare a un percorso casuale di un'ora tra fisica, filosofia, politica e storia. Questo potrebbe significare saltare un pranzo, dice Michael Sutherland, un collega di Cambridge - "ma saranno le ore più produttive che avrai in tutta la settimana". Le telefonate con i pari spesso durano fino alle prime ore della mattina, e nelle rare occasioni in cui Lonzarich va a una conferenza, invariabilmente attira una massa di colleghi. "Le persone che lo incontrano anche solo una volta o due sviluppano un senso di attaccamento e di timore", dice Louis Taillefer, un altro ex studente, ora fisico dell'Università di Sherbrooke, in Canada.

A 72 anni, Lonzarich ha ora un ruolo part-time nel gruppo di fisica quantistica della materia di Cambridge, ma sta ancora facendo nuove scoperte e spingendo i materiali verso limiti sempre più estremi. Considera questo regno, ancora in gran parte inesplorato, altrettanto importante per svelare le leggi della fisica come gli esperimenti ad alte energie negli acceleratori di particelle, e si aspetta che ci sia ancora molto da scoprire. "Gil non ha mai creduto che ora ci stiamo occupando dei dettagli", afferma Piers Coleman, fisico teorico della Rutgers University di Piscataway, nel New Jersey. "Vede l'esplorazione della materia quantistica come una vera frontiera".

Sforzi collettivi

Camminando attorno a un vecchio studio del Trinity College di Cambridge, Lonzarich ci tiene far notare un ritratto dell'economista John Kenneth Galbraith, uno dei suoi eroi, e parla con entusiasmo dell'impressionante lavoro dei suoi colleghi. Ma quando la conversazione riguarda i suoi successi, Lonzarich diventa reticente. È nella natura umana celebrare gli eroi, dice, ma la scienza è un'attività collettiva e lodare i singoli individui soffoca il lavoro di squadra. Anche se i colleghi sono pronti a mettere in risalto l'influenza di Lonzarich, lui non lo farebbe mai, per un'abitudine che potrebbe essere fatta risalire alla sua educazione, ricevuta da genitori italiani in Istria. Suo padre gli diceva di "tagliare sempre la fetta più grande della torta per l'altra persona", ricorda. A scuola, studiò la storia dell'antica Roma repubblicana e fu incuriosito dall'importanza attribuita alla ragione, al compromesso e al governo collaborativo.

La sua famiglia si trasferì negli Stati Uniti quando lui aveva nove anni. Negli anni sessanta, Lonzarich divenne un giovane studioso. Il suo interesse per la fisica iniziò all'Università della California a Berkeley, dove si laureò. Fu lì che conobbe Gerie Simmons (ora Lonzarich). I due si piacevano, e fu lei a combinare l'incontro, fingendo di aver bisogno di un tutor di fisica; si sposarono nel 1967.

"Nelle rare occasioni in cui ho potuto vedere sue fotografie di quel periodo, aveva i capelli lunghi. Era un hippy della fisica", dice Coleman. Ma anche se Lonzarich credeva fortemente che il popolo dovesse sfidare il governo, per esempio sulla guerra degli Stati Uniti in Vietnam, sviluppò una forma di disillusione quando vide le droghe libere e il rifiuto della famiglia della controcultura. "Volevo essere in grado di fare qualcosa di tangibile, per sfruttare al meglio la mia vita. E non mi sembrava che lo stessimo facendo", dice.

Dopo aver trascorso un periodo all'Università del Minnesota a Minneapolis, il lato oscuro del movimento alla fine spinse Gerie e Gil lontano dagli Stati Uniti fino all'Università della British Columbia a Vancouver, in Canada. Lonzarich subì il fascino del magnetismo, mentre lavorava al suo dottorato in un nuovo laboratorio guidato dal fisico della materia condensata Andrew Gold. Quando nel 1976 si trasferì per un periodo a Cambridge, trovò la sua nuova Roma. La struttura accademica non aveva una vera e propria gerarchia e poteva vantare la presenza di due giganti della fisica della materia fisica condensata come Brian Pippard e David Shoenberg. Quella che doveva essere un'avventura europea di un anno finì per durare più di quarant'anni.

Lonzarich arrivò a Cambridge per studiare i magneti, materiali in cui gli spin di elettroni si allineano spontaneamente. In un primo momento il suo approccio fu accolto con un certo scetticismo: sviluppò una sua notazione matematica e trascorreva settimane per preparare i suoi esperimenti, mentre sembrava non fare nulla. Ma i suoi metodi presto cominciarono a dare frutti.

Nei materiali magnetici, gli spin mantengono la loro disposizione ordinata solo fino a un certo punto; al di sopra di una certa temperatura, gli elettroni hanno così tanta energia che possono facilmente superare le forze che provocano l'allineamento dei loro spin. Lonzarich riteneva che il modo migliore per capire i materiali magnetici fosse spingerli fino a quel punto, dove sarebbero stati sul crinale che separa l'ordine dal disordine. In particolare, era interessato a studiare ciò che avrebbe potuto accadere se la transizione magnetica fosse stata spostata in modo che gli effetti quantistici potessero alterare lo stato del materiale.

A pressioni più alte, la transizione avviene a temperature più basse. E con una pressione sufficiente, un materiale può essere "sintonizzato" in modo che il suo punto di transizione magnetico si trovi vicino allo zero assoluto. Qui, le vibrazioni termiche non forniscono energia sufficiente a far perdere l'ordine magnetico al materiale. Invece, le fluttuazioni quantistiche – le variazioni transitorie nelle proprietà elettroniche, come velocità e posizione, causate dall'incertezza intrinseca del mondo quantico – dominano e possono causare nel materiale transizioni di stato. In questo regime, una regione attorno a un punto prossimo allo zero assoluto chiamato punto critico quantistico, i materiali magnetici diventano instabili e vacillano sull'orlo del magnetismo: non sono ordinati, ma sono impazienti di allinearsi.

Con le forze fisiche più grandi soppresse intorno al punto critico quantistico, le interazioni, solitamente deboli, tra gli elettroni possono avere effetti enormi. E potrebbero generare, argomentava Lonzarich, nuovi stati della materia attraverso la loro interazione collettiva. "È come in una foresta: le piccole piante non crescono fino a quando il grande albero non viene tagliato", dice. In particolare, Lonzarich ha previsto che gli antiferromagneti – i materiali magnetici in cui gli spin vicini tra loro si allineano in direzioni opposte al di sotto una determinata temperatura – sarebbero diventati superconduttori in prossimità del punto critico quantistico. Alla convergenza col magnetismo, pensava, gli elettroni sarebbero stati così desiderosi di allinearsi da formare spontaneamente coppie con spin opposti. Queste coppie antiparallele si sarebbero legate tra loro e la loro attrazione reciproca avrebbe stabilizzato il loro cammino attraverso il reticolo atomico del materiale.

A partire dalla metà degli anni ottanta, diversi fisici teorici suggerirono che potesse emergere una simile superconduttività mediata dal magnetismo, ma il gruppo di Lonzarich fu il primo a fornire una solida prova sperimentale. Quando il gruppo spinse un campione di cerio indio-3 antiferromagnetico vicino al punto critico quantistico, raffreddandolo ad alta pressione, i ricercatori lo videro passare in una fase superconduttiva, un fenomeno mai osservato in un materiale magnetico. Questo lavoro del 1994 dimostrò l'esistenza di una nuova categoria di superconduttori. Inoltre, indicò la via per la ricerca di altri materiali superconduttori. Attualmente, i fisici spingono regolarmente la transizione di fase nei materiali magnetici fino allo zero assoluto per vedere se emerge questo comportamento.

Un nuovo territorio

Il punto critico quantistico, e le forti interazioni quantistiche che possono avvenire intorno a esso, possono dare origine ad altri stati esotici, non solo alla superconduttività. "È come un terreno di coltura per scoprire nuovi stati della materia", spiega Stephen Rowley, fisico di Cambridge. I fisici di tutto il mondo ora manipolano una serie di fattori diversi – pressione, campi magnetici e composizione chimica – per spingere le transizioni di fase verso temperature più basse e quindi avvicinarsi a un punto critico quantistico.

Alla fine degli anni novanta, questo metodo ha portato Lonzarich e poi lo studente Christian Pfleiderer a scoprire un comportamento strano nel materiale noto come siliciuro di manganese. Gli esperimenti fatti negli ultimi anni hanno suggerito che questo può essere connesso a vortici magnetici bidimensionali, noti come skyrmioni, che furono descritti successivamente da Pfleiderer e i suoi colleghi e che sono ora considerati come un modo super-efficiente per memorizzare informazioni. Studiando la zona intorno a un punto critico quantistico del rutenato di stronzio ossido, nel 2007 Mackenzie e il suo gruppo hanno confermato l'esistenza di una nuova fase della materia, in cui gli elettroni fluiscono ma presentano ancora una struttura spaziale ordinata.

I colleghi fisici dicono che Lonzarich è unico: non solo è un buon fisico teorico ma anche uno sperimentatore eccezionale. "Devi tornare indietro a Enrico Fermi per trovare qualcuno in grado di pensare così profondamente alla teoria e di fare esperimenti veramente significativi", afferma David Pines, fisico e professore dell'Università della California a Davis. Lonzarich realizza campioni a livelli estremi di purezza ed è stato un pioniere in una tecnica nota come oscillazione quantistica, che permette ai fisici di determinare la struttura elettronica di sistemi complessi e tra loro interagenti. Patricia Alireza, che gestisce il laboratorio per le alte pressioni nel Cavendish Laboratory di Cambridge, afferma che Lonzarich la incoraggia spesso a creare dispositivi che portano i campioni ben oltre quello che si ritiene possibile. "Gil di solito sorride e dice: 'Penso che probabilmente possiamo fare meglio di un fattore 100', e sai che cosa succede? Ci riusciamo sempre".

Molti degli studenti di Lonzarich hanno continuato la loro carriera nel campo della fisica e hanno avuto successo. Suchitra Sebastian, per esempio, qualche anno fa ha guidato il lavoro con Lonzarich sull'esaboruro di samario, un isolante che mostra un comportamento simile al metallo quando è sottoposto a forti campi magnetici. Dice che senza il suo consiglio avrebbe probabilmente mollato. "Non ti sta solo insegnando 'è così che si fa fisica', ma anche 'è così che si sopravvive nel mondo della fisica' ", dice. Lonzarich si esprime con modestia quando parla del suo contribuito al successo di coloro di cui è stato mentore: ha imparato tanto quanto ha insegnato, dice.

Una cosa che ha sempre per le persone è il tempo, dice Rowley. È utile che sia abile a sfuggire alla burocrazia inutile, aggiunge Pines. "Ha molti uffici diversi, in modo da potersi sempre nascondere". Ma la libertà di pensiero di Lonzarich è ampiamente garantita dalla moglie Gerie, che si assicura che le domande di fondi siano consegnate in tempo e che i voli vengano presi. Gil dice che sua moglie è come il Sole: "Così grande e importante che a volte dimentichi che è il motivo per cui tutto esiste".

Un mistero rimasto in piedi

Negli ultimi anni le idee di Lonzarich sull'intimo legame tra superconduttività e magnetismo hanno guadagnato nuova rilevanza. I fisici spiegano la superconduttività convenzionale usando la teoria BCS, così chiamata dalle iniziali dei cognomi delle tre persone che l'hanno pubblicata nel 1957. La teoria afferma che un elettrone che si muove attraverso alcuni materiali crea una distorsione carica positivamente nel reticolo atomico che si lascia dietro. Ciò attira un secondo elettrone, che segue il primo come un ciclista che si attacca alla ruota di chi lo precede. Se si forma un numero sufficiente di queste "coppie Cooper" relativamente stabili, si crea uno stato ordinato in cui i due elettroni si tengono l'un l'altro nella direzione giusta e fluiscono senza resistenza.

Rappresentazione schematica di una coppia di Cooper (rosso) che si muove all'interno di un reticolo di un materiale. (Wikimedia Commons) / Schematic representation of a pair of Cooper (red) moving inside a lattice of a material.

Ma questa spiegazione non può rendere conto dei sandwich di isolanti a base di rame noti come cuprati e dei semiconduttori a base di ferro. Queste due classi di superconduttori possono trasportare correnti senza resistenza a temperature fino a 133 kelvin. Se queste transizioni venissero portate a temperatura ambiente, circa 300 kelvin, questi superconduttori potrebbero garantire energia, imaging diagnostico e trasporti a basso costo. Ma il dibattito su come funzionano si è protratto per trent'anni.

Fin dall'inizio, si è formato un partito di coloro che pensavano che l'interazione magnetica – che può essere più resistente alla temperatura rispetto alle interazioni causate dalle distorsioni nel reticolo – potesse in qualche modo legare gli elettroni per generare superconduttività nei cuprati. Lonzarich ha teorizzato che questa colla magnetica potrebbe derivare dalle stesse fluttuazioni quantistiche che si attivano nei punti critici quantistici antiferromagnetici. Quest'idea è attualmente molto dibattuta, e ha guadagnato qualche prova a supporto lo scorso anno, negli esperimenti condotti dal gruppo di Taillefer, con i collaboratori del francese Laboratoire National des Champs Magnétiques Intenses di Tolosa. Il gruppo ha scoperto che privando un cuprato della sua superconduttività con un potente campo magnetico e aggiungendo livelli crescenti di impurità si arriva a una brusca transizione di fase, un punto critico quantistico altrimenti nascosto. Anche se la precisa natura di quel punto non è ancora chiara, sembra probabile che siano coinvolte le correlazioni antiferromagnetiche, spiega Taillefer. "Ciò significa che Gil ha avuto un'intuizione incredibile", dice.

Lonzarich ora sta guardando oltre i convenzionali superconduttori ad alta temperatura. Con Rowley e altri colleghi sta esaminando la natura dei materiali ferroelettrici, una classe di materiali ionici poco studiata che generano il proprio campo elettrico. A bassa temperatura, i materiali ferroelettrici possono diventare superconduttori, secondo un fenomeno molto simile all'emergere della superconduttività nei materiali magnetici. Lonzarich ha il presentimento che, nei materiali ferroelettrici che mostrano anche magnetismo, le coppie di elettroni si legano così forte tra loro che lo stato potrebbe sopravvivere a temperatura ambiente.

L'universo è più ricco di quello che pensa la maggior parte dei ricercatori, afferma Lonzarich. Ogni nuovo stato della materia scoperto emerge solo quando le condizioni sono giuste e un materiale è sufficientemente puro. Lonzarich ipotizza che studiare i confini intorno a quegli stati potrebbe rivelare ancora più fasi e studiare i confini di quelli potrebbe rivelarne ancora di più, con campi di nuove scoperte che si aprirebbero come in un frattale. "Che cosa succederebbe se ogni punto critico quantistico fosse solo l'inizio di un'altra generazione di punti critici? C'è qualche indicazione che siamo in quella direzione", dice.

L'idea è assai speculativa, ma Taillefer dice che sarebbe saggio considerarla. La nozione che un principio ormai familiare potrebbe nascondere un comportamento profondo e complesso “è tipica di Gil", dice. "Sarei disposto a metterci anche del denaro".

ENGLISH

Gilbert Lonzarich for over forty years was a pioneer in the study of condensed matter physics. His ideas, initially welcomed with distrust, have become the basis for studies of exotic states that are produced when the effects of extreme temperatures and pressures intersect those of quantum mechanics.

In 1989, a retinal detachment surgery left Gilbert Lonzarich blind for a month. Rather than feeling shaken or depressed, the condensed physicist at the University of Cambridge in the UK took the opportunity to invite his graduate students home to share with them how enthusiastic it was to adapt to unseen life. The way Lonzarich embraced this experience seamlessly captures his approach to life, says Andrew Mackenzie, then a student and now director of the Max-Planck Institute for Solid Physics in Dresden, Germany. "Gil is one of the most positive people I have ever met: he is interested in everything," he says.

For over forty years, optimism and curiosity led Lonzarich to study the materials in ways they did not think possible. In a series of pioneering experiments of the nineties, his group has shown that bringing magnetic compounds to extreme pressures and close to absolute zero can cause some of them to lead unbiased electricity. This went against conventional thinking that magnetism and superconductivity could never have been mixed. "It was like talking today about finding aliens or something," explains Malte Grosche, his colleague at Cambridge.

That work has shown physicists a new way of hunting superconductors, which are the heart of technologies such as magnetic resonance scanners and particle accelerators. In recent years, it has offered a possible explanation for the fact that some materials remain superconducting at temperatures much higher than absolute zero, which could pave the way for the development of efficient and economical devices that super-conduct at room temperature.

But experiments have had an impact far beyond superconductivity. Lonzarich's method of subjecting materials to extreme conditions has become a general recipe for discovering new states of matter. Worldwide, physicists now use this approach to study a range of materials in which collective interactions of electrons can give rise to unusual behaviors. Some of these phenomena could revolutionize computers.

The pursuit of Lonzarich can be legendary in his community, but the humility and generosity of physics are what make him appreciate his colleagues. His unknowingness of the flow of time is famous; a casual conversation with Lonzarich can easily lead to an hour-long casual path between physics, philosophy, politics and history. This could mean skip a lunch, says Michael Sutherland, a Cambridge colleague - "but it will be the most productive hours you'll have throughout the week." Phone calls with peers often last until the early hours of the morning, and in rare occasions when Lonzarich goes to a conference invariably attracts a mass of colleagues. "People who meet him only once or twice develop a sense of attachment and fear," says Louis Taillefer, another former student at the University of Sherbrooke, Canada.

At 72, Lonzarich now has a part-time role in the quantum physics group of Cambridge, but is still making new discoveries and pushing materials into ever-increasing limits. Consider this reign, still largely unexplored, just as important to unveiling the laws of physics as the high-energy experiments in particle accelerators, and expects there is still much to discover. "Gil never believed that we are now dealing with details," says Piers Coleman, theoretical physicist at Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey. "You see the exploration of quantum matter as a true frontier."

Collective effortsWalking around an old study at Trinity College in Cambridge, Lonzarich tells us a portrait of economist John Kenneth Galbraith, one of his heroes, and talks with enthusiasm about the impressive work of his colleagues. But when the conversation concerns his achievements, Lonzarich becomes reticent. It is in human nature to celebrate heroes, he says, but science is a collective activity and praise individual individuals stifle teamwork. Although colleagues are ready to emphasize the influence of Lonzarich, he would never do it, for a habit that could be traced back to his education, received by Italian parents in Istria. His father told him "always cut the bigger slice of the cake for the other person," he remembers. At school, he studied the history of ancient republican Rome and was curious about the importance attributed to reason, compromise, and collaborative government.

His family moved to the United States when he was nine years old. In the sixties, Lonzarich became a young scholar. His interest in physics began at the University of California at Berkeley, where he graduated. It was there that he met Gerie Simmons (now Lonzarich). The two liked it, and she had to combine the encounter, pretending to need a physical tutor; they married in 1967.

"On rare occasions when I could see her photographs of that period, she had long hair. It was a physics hippie," says Coleman. But even though Lonzarich strongly believed that the people were to challenge the government, for example, on the US war in Vietnam, he developed a form of disillusion when he saw the free drugs and the rejection of the counterculture family. "I wanted to be able to do something tangible, to make the most of my life. And I did not think we were doing it," he says.

After spending a period at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, the dark side of the movement eventually pushed Gerie and Gil away from the United States to the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Lonzarich suffered the charm of magnetism as he worked at his doctorate in a new laboratory led by the condensed physicist Andrew Gold. When in 1976 he moved for a period to Cambridge, he found his new Rome. The academic structure did not have a true hierarchy and could boast the presence of two physics giants of condensed physical matter such as Brian Pippard and David Shoenberg. What was to be a one-year European adventure lasted for over forty years.

Lonzarich came to Cambridge to study the magnets, materials in which the spin of electrons align themselves spontaneously. At first his approach was met with some skepticism: he developed his mathematical notation and spent weeks preparing his experiments while he seemed to do nothing. But his methods soon began to bear fruit.

In magnetic materials, spin keeps their ordered arrangement up to a certain point; above a certain temperature, electrons have so much energy that they can easily overcome the forces that cause the alignment of their spins. Lonzarich believed that the best way to understand the magnetic materials was to push them to that point, where they would be on the crest that separates the order from the disorder. In particular, he was interested in studying what could have happened if the magnetic transition had been shifted so that quantum effects could alter the state of the material.

At higher pressures, the transition takes place at lower temperatures. And with sufficient pressure, a material can be "tuned" so that its magnetic transition point is close to absolute zero. Here, thermal vibrations do not provide enough energy to lend the magnetic order to the material. Instead, quantum fluctuations - transient changes in electronic properties, such as speed and position, caused by the intrinsic uncertainty of the quantum world - dominate and may cause state transition transitions. In this regime, a region around an absolute zero point called a quantum critical point, magnetic materials become unstable and wobble over the brim of magnetism: they are not sorted, but are impatient to align themselves.

In magnetic materials, spin keeps their ordered arrangement up to a certain point; above a certain temperature, electrons have so much energy that they can easily overcome the forces that cause the alignment of their spins. Lonzarich believed that the best way to understand the magnetic materials was to push them to that point, where they would be on the crest that separates the order from the disorder. In particular, he was interested in studying what could have happened if the magnetic transition had been shifted so that quantum effects could alter the state of the material.

At higher pressures, the transition takes place at lower temperatures. And with sufficient pressure, a material can be "tuned" so that its magnetic transition point is close to absolute zero. Here, thermal vibrations do not provide enough energy to lend the magnetic order to the material. Instead, quantum fluctuations - transient changes in electronic properties, such as speed and position, caused by the intrinsic uncertainty of the quantum world - dominate and may cause state transition transitions. In this regime, a region around an absolute zero point called a quantum critical point, magnetic materials become unstable and wobble over the brim of magnetism: they are not sorted, but are impatient to align themselves.

With larger physical forces suppressed around the quantum critical point, the interactions, usually weak, between electrons can have enormous effects. And they could create, argue Lonzarich, new states of matter through their collective interaction. "It's like in a forest: small plants do not grow until the big tree is cut off," she says. In particular, Lonzarich has predicted that anti-magnetic magnets - the magnetic materials in which the spins adjacent to each other align themselves in opposite directions below a certain temperature - would become superconductors near the quantum critical point. At convergence with magnetism, she thought, electrons would be so eager to align themselves to spontaneously form pairs with opposite spin. These antiparallel pairs would be linked to each other and their mutual attraction would stabilize their path through the atomic material grid.

Since the mid-1980s, several theoretical physicists suggested that such a superconductivity mediated by magnetism could emerge, but Lonzarich's group was the first to provide solid experimental evidence. When the group launched an anti-hemicromagnetic cerio-3 cytoplasm near the quantum critical point, cooled by high pressure, the researchers saw it pass into a superconductive phase, a phenomenon never observed in a magnetic material. This 1994 work demonstrated the existence of a new category of superconductors. It also paved the way for the search for other superconducting materials. At present, physicists regularly push phase transition into magnetic materials up to absolute zero to see if this behavior emerges.

A new territoryThe quantum critical point, and the strong quantum interactions that may occur around it, can give rise to other exotic states, not just superconductivity. "It's like a cultivation ground to discover new states of matter," explains Stephen Rowley, a physicist at Cambridge. Physicists around the world now manipulate a number of different factors - pressure, magnetic fields, and chemical composition - to push phase transitions to lower temperatures and then approach a quantum critical point.

In the late nineties, this method led Lonzarich and then Christian Pfleiderer to discover strange behavior in the material known as manganese silicon. Experiments made in recent years have suggested that this can be related to two-dimensional magnetic vortexes, known as skyrmions, which were later described by Pfleiderer and his colleagues and are now considered a super-efficient way to store information. Studying the area around a quantum critical point of strontium oxide ruthenium, in 2007 Mackenzie and his group confirmed the existence of a new phase of matter, in which electrons flow but still have an ordered space structure.

Physical colleagues say that Lonzarich is unique: not only is it a good theoretical physicist but also an exceptional experimentator. "You have to go back to Enrico Fermi to find someone who can think so deeply of theory and make really meaningful experiments," says David Pines, physicist and professor at the University of California at Davis. Lonzarich produces specimens at extreme levels of purity and has been a pioneer in a technique known as quantum oscillation, which allows physicists to determine the complex structure and interaction between complex electronic systems. Patricia Alireza, who runs the lab for high pressures at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, says that Lonzarich often encourages her to create devices that bring samples far beyond what she thinks possible. "Gil usually smiles and says, 'I think we can probably do better than a factor of 100' and you know what's going on? We always do it."

Many of Lonzarich's students continued their career in physics and were successful. Suchitra Sebastian, for example, a few years ago led the work with Lonzarich on samarium processing, an insulator that exhibits metal-like behavior when subjected to strong magnetic fields. He says that without his advice he would probably have given up. "It's not just teaching you so it's physical, but it's just so that you survive in the world of physics," he says. Lonzarich is modest when speaking about his contribution to the success of those he has been mentor: he has learned as much as he has taught, he says.

One thing that people always have is time, says Rowley. It is useful to be able to escape unnecessary bureaucracy, Pines adds. "He has many different offices, so he can always hide." But Lonzarich's freedom of thought is largely guaranteed by his wife, Gerie, who ensures that fundraising requests are delivered on time and that flights are taken. Gil says his wife is like the sun: "It's great and important that sometimes you forget that's why everything exists."

A mystery remainedIn recent years, Lonzarich's ideas on the intimate bond between superconductivity and magnetism have gained new relevance. Physicists explain conventional superconductivity using BCS theory, so called from the initials of the three-person surnames that published it in 1957. The theory states that an electron that moves through some materials creates a positively charged distortion in the atomic grid that is leave behind. This attracts a second electron, which follows the first as a cyclist attaching to the wheel of those who precede it. If a sufficient number of these "Cooper pairs" are formed relatively stable, an orderly state is created where the two electrons hold each other in the right direction and flow without resistance.

But this explanation can not account for copper-based sandwich insulators known as cuprats and iron-based semiconductors. These two superconductor classes can carry currents without resistance at temperatures up to 133 kelvin. If these transitions were brought to room temperature, about 300 kelvin, these superconductors could provide energy, diagnostic imaging and low cost transport. But the debate on how it worked lasted for thirty years.

From the very beginning, a party was formed of those who thought that magnetic interaction - which could be more resistant to temperature than the interactions caused by distortions in the lattice - could somehow bind the electrons to generate superconductivity in the cuprates. Lonzarich has theorized that this magnetic glue could derive from the same quantum fluctuations that are activated at the quantum anti-ferromagnetic points. This idea is currently very much debated, and has gained some evidence to support last year, in the experiments conducted by the Taillefer group, with the collaborators of the French Laboratoire National des Champs Magnétiques Intenses of Toulouse. The group found that by depriving a cuprat of its superconductivity with a powerful magnetic field and adding increasing levels of impurities, it comes to a sudden phase transition, a quantum critical point otherwise hidden. Although the precise nature of that point is still unclear, it seems likely that anti-hemoglobin correlations are involved, says Taillefer. "That means Gil had an incredible intuition," he says.

Lonzarich is now looking beyond the conventional high temperature superconductors. With Rowley and other colleagues he is examining the nature of ferroelectric materials, a class of unmanaged ionic materials that generate their own electric field. At low temperatures, ferroelectric materials can become superconductors, according to a phenomenon very similar to the emergence of superconductivity in magnetic materials. Lonzarich has the impression that in electromagnetic materials that show even magnetism, electron pairs are so strong that the state may survive at room temperature.

The universe is richer than most thinkers think, says Lonzarich. Every new state of uncovered matter emerges only when the conditions are right and a material is sufficiently pure. Lonzarich hypothesizes that studying the boundaries around those states could reveal even more stages and studying the boundaries of those could reveal even more, with fields of new discoveries that would open as in a fractal. "What would happen if every quantum critical point was just the beginning of another generation of critical points? There is some indication that we are in that direction," he says.

The idea is very speculative, but Taillefer says it would be wise to consider it. The notion that a familiar principle could conceal deep and complex behavior "is typical of Gil," he says, "I would be willing to put some money on us too."

Da:

http://www.lescienze.it/news/2017/09/30/news/pioniere_segreti_quantistici_materia-3682912/

Commenti

Posta un commento