Measles erases the immune system’s memory / Il morbillo cancella la memoria del sistema immunitario

Measles erases the immune system’s memory / Il morbillo cancella la memoria del sistema immunitario

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

Beyond the rash, the infection makes it harder for the body to remember and attack other invaders.

The most iconic thing about measles is the rash — red, livid splotches that make infection painfully visible.

But that rash, and even the fever, coughing and watery, sore eyes, are all distractions from the virus’s real harm — an all-out attack on the immune system.

Measles silently wipes clean the immune system’s memory of past infections. In this way, the virus can cast a long and dangerous shadow for months, or even years, scientists are finding. The resulting “immune amnesia” leaves people vulnerable to other viruses and bacteria that cause pneumonia, ear infections and diarrhea.

Those aftereffects make measles “the furthest thing from benign,” says infectious disease epidemiologist and pathologist Michael Mina of Harvard University. “It really puts you at increased susceptibility for everything else.” And that has big consequences, recent studies show.

Details about which immune cells are most at risk and how long the immune system seems to suffer — gleaned from studies of lab animals, human tissue and children before and after they had measles — have created a more complete picture of how the virus mounts its sneak attack.

This new view may help explain a larger-than-expected umbrella of safety created by measles vaccination. “Wherever you introduce measles vaccination, you always reduce childhood mortality. Always,” says virologist Rik de Swart of Erasmus University Medical Center in the Netherlands. The shot prevents deaths, and more than just those caused by measles. By shielding the immune system against one virus’s attack, the vaccine may create a kind of protective halo that keeps other pathogens at bay, some researchers suspect.

Locking onto a target

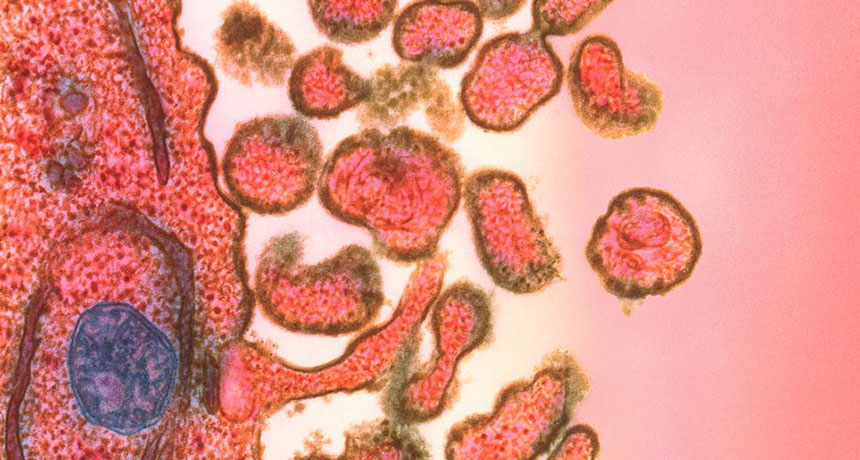

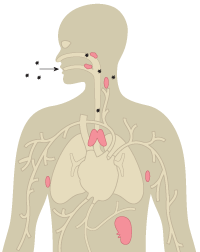

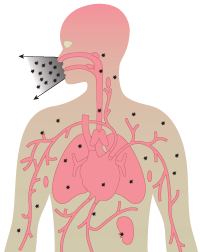

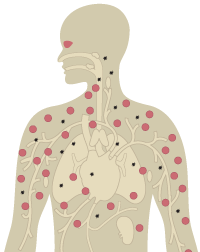

After an infected person coughs or sneezes, the measles virus can linger in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours, waiting to make its way into the airways of its next victims. Once inside, the virus is thought to target immune cells found in the mucus of the nose and throat, the tiny air sacs in the lungs or between the eyelids and cornea. These immune cells are decorated with a protein called CD150 that allows the virus to invade, experiments on animals suggest.

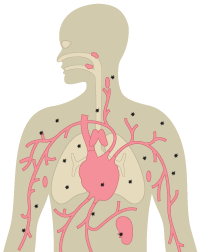

The virus quickly replicates inside the cells, then spreads to places packed with other immune cells — bone marrow, thymus, spleen, tonsils and lymph nodes. “The virus has an enormously strong predilection to infect cells of the immune system,” says Bert Rima, an infectious disease researcher at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland. Rima and colleagues traced the immune system invasion in preserved human tissue, reporting results in 2018 in mSphere. Eventually, newly made viral particles move into the respiratory tract, where they can be coughed out to sicken more people.

An acute measles infection, which usually lasts several weeks, can sometimes bring ear infections, pneumonia and, rarely, a deadly brain swelling. On their own, those are worrisome outcomes, says Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md. But the loss of immune cells can also leave people vulnerable to infections that the immune system would normally be able to handle.

In 2013, de Swart and colleagues saw an opportunity to study the immune effects of the virus in children who are part of an insular community of Orthodox Protestants in the Netherlands, called the Dutch Bible Belt. Parents there refuse vaccinations, a decision that ushers in regular bouts of measles. The community’s last measles outbreak ended in 2000; it was just a matter of time before the virus took hold again.

The researchers got permission from parents to take blood samples from healthy, unvaccinated children to study their immune cells. Then, the researchers waited for an outbreak, so they could test the kids again after an infection.

De Swart didn’t have to wait long. Just as the researchers began collecting blood, an outbreak emptied classrooms, packing sick siblings into dark living rooms to protect their sensitive eyes. As the virus ripped through the community, de Swart and colleagues collected before and after samples from 77 children who contracted measles.

“The virus preferentially infects cells in the immune system that carry the memory of previously experienced infections,” de Swart says. Called memory B and T cells, these cellular protectors normally remember threats the body has already neutralized, allowing the immune system to spring into action quickly if those threats return. After a measles infection, the numbers of some types of these memory cells dropped, creating an immune amnesia, the researchers reported in 2018 in Nature Communications.

Long road to recovery

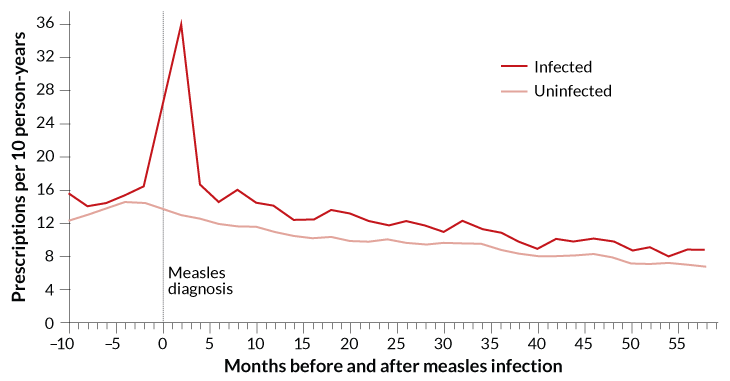

The immune system might take months, or even years, to bounce back from this memory loss. Researchers including de Swart and Mina compared health records of U.K. children from 1990 to 2014. For up to five years after their bout of measles, children who had previously had the virus experienced more diagnosed infections than children who hadn’t. Children who’d had measles were 15 to 24 percent more likely to receive a prescription for an infection than children who never had measles, the researchers reported in 2018 in BMJ Open.

Mina and colleagues found similar results for deaths from nonmeasles infections in children in England, Wales, the United States and Denmark, before and after the introduction of the measles vaccine. When measles was rampant, children were more likely to die from other infections.

When the researchers looked out several years after the measles, the connection between measles and nonmeasles deaths grew stronger (SN: 5/30/15, p. 10). “Every little blip in the mortality data could be explained by the measles incidence data over the previous 30 months,” Mina says. It’s not clear how the immune system eventually recovers its memories. With new methods that can measure these cellular memories, Mina and others hope to understand that rebuilding process.

Most children get over measles uneventfully. “The immune system is incredibly resilient,” de Swart says. Still, measles is not an innocent childhood disease. For some people, the consequences can be severe. But there’s a vaccine for that. “At the end of the day, we know how to prevent this potentially lethal disease,” Mina says. “It’s so simple.”

ITALIANO

Oltre l'eruzione cutanea, l'infezione rende più difficile per il corpo ricordare e attaccare altri invasori.

La cosa più iconica del morbillo sono le chiazze rosse e livide che rendono dolorosamente visibile l'infezione.

Ma quell'eruzione cutanea e persino la febbre, la tosse e lacrimazione, gli occhi doloranti, sono tutte distrazioni dal vero danno del virus - un attacco a tutto campo al sistema immunitario.

Il morbillo pulisce silenziosamente la memoria del sistema immunitario dalle infezioni passate. Gli scienziati stanno scoprendo che In questo modo, il virus può gettare un'ombra lunga e pericolosa per mesi o addirittura anni. La conseguente "amnesia immunitaria" rende le persone vulnerabili ad altri virus e batteri che causano polmonite, infezioni alle orecchie e diarrea.

Questi effetti collaterali rendono il morbillo "la cosa più lontana dal benigno", afferma l'epidemiologo e patologo Michael Mina dell'Università di Harvard. "Ti mette davvero a una maggiore suscettibilità per tutto il resto." Studi recenti mostrano che questo ha grandi conseguenze,

I dettagli su quali cellule immunitarie sono maggiormente a rischio e per quanto tempo sembra soffrire il sistema immunitario - ricavato da studi su animali da laboratorio, tessuti umani e bambini prima e dopo aver avuto il morbillo - hanno creato un quadro più completo di come il virus organizza il suo attacco.

Questa nuova visione può aiutare a spiegare una motivazione di sicurezza più ampia del previsto creato dalla vaccinazione contro il morbillo. “Ovunque si introduca la vaccinazione contro il morbillo, riduci sempre la mortalità infantile. Sempre ", afferma il virologo Rik de Swart del Centro medico dell'Università Erasmus nei Paesi Bassi. Il colpo previene le morti e più di quelle causate dal morbillo. Proteggendo il sistema immunitario dall'attacco di un virus, il vaccino può creare una sorta di alone protettivo che tiene a bada altri agenti patogeni, sospettano alcuni ricercatori.

Bloccarsi su un bersaglio

Dopo che una persona infetta tossisce o starnutisce, il virus del morbillo può indugiare nell'aria e sulle superfici per un massimo di due ore, in attesa di farsi strada nelle vie aeree delle sue prossime vittime. Una volta all'interno, si pensa che il virus colpisca le cellule immunitarie presenti nel muco del naso e della gola, le minuscole sacche d'aria nei polmoni o tra le palpebre e la cornea. Esperimenti su animali suggeriscono che queste cellule immunitarie sono decorate con una proteina chiamata CD150 che consente al virus di invadere.

Il virus si replica rapidamente all'interno delle cellule, quindi si diffonde in luoghi pieni di altre cellule immunitarie: midollo osseo, timo, milza, tonsille e linfonodi. "Il virus ha una fortissima predilezione per infettare le cellule del sistema immunitario", afferma Bert Rima, ricercatore di malattie infettive presso la Queen's University di Belfast, nell'Irlanda del Nord. Rima e colleghi hanno tracciato l'invasione del sistema immunitario nei tessuti umani preservati, riportando i risultati nel 2018 in mSphere. Alla fine, le particelle virali di nuova produzione si spostano nel tratto respiratorio, dove possono essere espulse per ammalare più persone.

Un'infezione acuta del morbillo, che di solito dura diverse settimane, a volte può causare infezioni alle orecchie, polmonite e, raramente, un mortale gonfiore al cervello. Da soli, questi sono risultati preoccupanti, afferma Anthony Fauci, direttore dell'Istituto nazionale di allergie e malattie infettive a Bethesda, nel Maryland. Ma la perdita di cellule immunitarie può anche rendere le persone vulnerabili alle infezioni che il sistema immunitario sarebbe normalmente in grado di debellare.

Nel 2013, de Swart e colleghi hanno visto un'opportunità per studiare gli effetti immunitari del virus nei bambini che fanno parte di una comunità insulare di protestanti ortodossi nei Paesi Bassi, chiamata cintura biblica olandese. I genitori rifiutano le vaccinazioni, una decisione che introduce regolari attacchi di morbillo. L'ultimo focolaio di morbillo della comunità è terminato nel 2000; era solo questione di tempo prima che il virus prendesse di nuovo piede.

I ricercatori hanno ottenuto il permesso dai genitori di prelevare campioni di sangue da bambini sani e non vaccinati per studiare le loro cellule immunitarie. Quindi, i ricercatori hanno aspettato un focolaio, in modo da poter testare nuovamente i bambini dopo un'infezione.

De Swart non dovette aspettare molto. Proprio quando i ricercatori hanno iniziato a raccogliere sangue, un focolaio ha svuotato le aule, mettendo i fratelli malati in salotti bui per proteggere i loro occhi sensibili. Mentre il virus si diffondeva nella comunità, de Swart e colleghi hanno raccolto campioni prima e dopo da 77 bambini che avevano contratto il morbillo.

"Il virus infetta preferibilmente le cellule del sistema immunitario che trasportano la memoria di infezioni precedentemente sperimentate", afferma de Swart. Chiamate cellule B e T di memoria, queste protezioni cellulari normalmente ricordano le minacce che il corpo ha già neutralizzato, consentendo al sistema immunitario di entrare rapidamente in azione se tali minacce ritornano. Dopo un'infezione da morbillo, il numero di alcuni tipi di queste cellule della memoria è diminuito, creando un'amnesia immunitaria, hanno riferito i ricercatori nel 2018 in Nature Communications.

Lunga strada per il recupero

Il sistema immunitario potrebbe richiedere mesi o addirittura anni per riprendersi da questa perdita di memoria. I ricercatori, tra cui de Swart e Mina, hanno confrontato i dati sanitari dei bambini del Regno Unito dal 1990 al 2014. Fino a cinque anni dopo il loro attacco di morbillo, i bambini che avevano precedentemente avuto il virus hanno avuto più infezioni diagnosticate rispetto ai bambini che non lo avevano fatto. I bambini che avevano avuto il morbillo avevano dal 15 al 24 percento in più di probabilità di ricevere una prescrizione per un'infezione rispetto ai bambini che non avevano mai avuto il morbillo, hanno riferito i ricercatori nel 2018 su BMJ Open.

Danno duraturo

I bambini del Regno Unito che avevano il morbillo (linea rossa) avevano maggiori probabilità di ricevere prescrizioni per medicine per altre infezioni rispetto ai bambini che non avevano avuto il morbillo (linea rosa) nei mesi e negli anni successivi.

Mina e colleghi hanno trovato risultati simili per i decessi per infezioni non cardiache nei bambini in Inghilterra, Galles, Stati Uniti e Danimarca, prima e dopo l'introduzione del vaccino contro il morbillo. Quando il morbillo dilagava, i bambini avevano maggiori probabilità di morire per altre infezioni.

Quando i ricercatori hanno guardato diversi anni dopo il morbillo, la connessione tra le morti di morbillo e non-morbillo è diventata più forte (SN: 30/05/15, p. 10). "Ogni piccola differenza nei dati di mortalità potrebbe essere spiegata dai dati di incidenza del morbillo negli ultimi 30 mesi", afferma Mina. Non è chiaro come il sistema immunitario alla fine recuperi i suoi ricordi. Con nuovi metodi in grado di misurare queste memorie cellulari, Mina e altri sperano di capire quel processo di ricostruzione.

La maggior parte dei bambini supera il morbillo senza incidenti. "Il sistema immunitario è incredibilmente resistente", afferma de Swart. Tuttavia, il morbillo non è una malattia infantile innocente. Per alcune persone, le conseguenze possono essere gravi. Ma c'è un vaccino per il morbillo. "Alla fine della giornata, sappiamo come prevenire questa malattia potenzialmente letale", afferma Mina. "È così semplice."

Nel 2013, de Swart e colleghi hanno visto un'opportunità per studiare gli effetti immunitari del virus nei bambini che fanno parte di una comunità insulare di protestanti ortodossi nei Paesi Bassi, chiamata cintura biblica olandese. I genitori rifiutano le vaccinazioni, una decisione che introduce regolari attacchi di morbillo. L'ultimo focolaio di morbillo della comunità è terminato nel 2000; era solo questione di tempo prima che il virus prendesse di nuovo piede.

I ricercatori hanno ottenuto il permesso dai genitori di prelevare campioni di sangue da bambini sani e non vaccinati per studiare le loro cellule immunitarie. Quindi, i ricercatori hanno aspettato un focolaio, in modo da poter testare nuovamente i bambini dopo un'infezione.

De Swart non dovette aspettare molto. Proprio quando i ricercatori hanno iniziato a raccogliere sangue, un focolaio ha svuotato le aule, mettendo i fratelli malati in salotti bui per proteggere i loro occhi sensibili. Mentre il virus si diffondeva nella comunità, de Swart e colleghi hanno raccolto campioni prima e dopo da 77 bambini che avevano contratto il morbillo.

"Il virus infetta preferibilmente le cellule del sistema immunitario che trasportano la memoria di infezioni precedentemente sperimentate", afferma de Swart. Chiamate cellule B e T di memoria, queste protezioni cellulari normalmente ricordano le minacce che il corpo ha già neutralizzato, consentendo al sistema immunitario di entrare rapidamente in azione se tali minacce ritornano. Dopo un'infezione da morbillo, il numero di alcuni tipi di queste cellule della memoria è diminuito, creando un'amnesia immunitaria, hanno riferito i ricercatori nel 2018 in Nature Communications.

Lunga strada per il recupero

Il sistema immunitario potrebbe richiedere mesi o addirittura anni per riprendersi da questa perdita di memoria. I ricercatori, tra cui de Swart e Mina, hanno confrontato i dati sanitari dei bambini del Regno Unito dal 1990 al 2014. Fino a cinque anni dopo il loro attacco di morbillo, i bambini che avevano precedentemente avuto il virus hanno avuto più infezioni diagnosticate rispetto ai bambini che non lo avevano fatto. I bambini che avevano avuto il morbillo avevano dal 15 al 24 percento in più di probabilità di ricevere una prescrizione per un'infezione rispetto ai bambini che non avevano mai avuto il morbillo, hanno riferito i ricercatori nel 2018 su BMJ Open.

Danno duraturo

I bambini del Regno Unito che avevano il morbillo (linea rossa) avevano maggiori probabilità di ricevere prescrizioni per medicine per altre infezioni rispetto ai bambini che non avevano avuto il morbillo (linea rosa) nei mesi e negli anni successivi.

Mina e colleghi hanno trovato risultati simili per i decessi per infezioni non cardiache nei bambini in Inghilterra, Galles, Stati Uniti e Danimarca, prima e dopo l'introduzione del vaccino contro il morbillo. Quando il morbillo dilagava, i bambini avevano maggiori probabilità di morire per altre infezioni.

Quando i ricercatori hanno guardato diversi anni dopo il morbillo, la connessione tra le morti di morbillo e non-morbillo è diventata più forte (SN: 30/05/15, p. 10). "Ogni piccola differenza nei dati di mortalità potrebbe essere spiegata dai dati di incidenza del morbillo negli ultimi 30 mesi", afferma Mina. Non è chiaro come il sistema immunitario alla fine recuperi i suoi ricordi. Con nuovi metodi in grado di misurare queste memorie cellulari, Mina e altri sperano di capire quel processo di ricostruzione.

La maggior parte dei bambini supera il morbillo senza incidenti. "Il sistema immunitario è incredibilmente resistente", afferma de Swart. Tuttavia, il morbillo non è una malattia infantile innocente. Per alcune persone, le conseguenze possono essere gravi. Ma c'è un vaccino per il morbillo. "Alla fine della giornata, sappiamo come prevenire questa malattia potenzialmente letale", afferma Mina. "È così semplice."

Da:

Commenti

Posta un commento