Cryo-EM Captures CRISPR-Cas9 Base Editor in Action / Cryo-EM acquisisce l'editor di base CRISPR-Cas9 in azione

Cryo-EM Captures CRISPR-Cas9 Base Editor in Action / Cryo-EM acquisisce l'editor di base CRISPR-Cas9 in azione

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

CRISPR-Cas9’s ability to cut and edit DNA have long been the focus of the genome editing story. But CRISPR-Cas–guided base editors, that specifically correct a common class of base substitutions without cleaving DNA, have recently moved into the spotlight.

In 2016, David Liu, PhD, a chemistry professor affiliated with Harvard University, the Broad Institute, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, combined Cas9 with another bacterial protein to allow the precise replacement of one nucleotide with another: the first base editor. Instead of cutting, base editors convert the nucleotides A•T to G•C, or C•G to T•A, in DNA for precision genome editing.

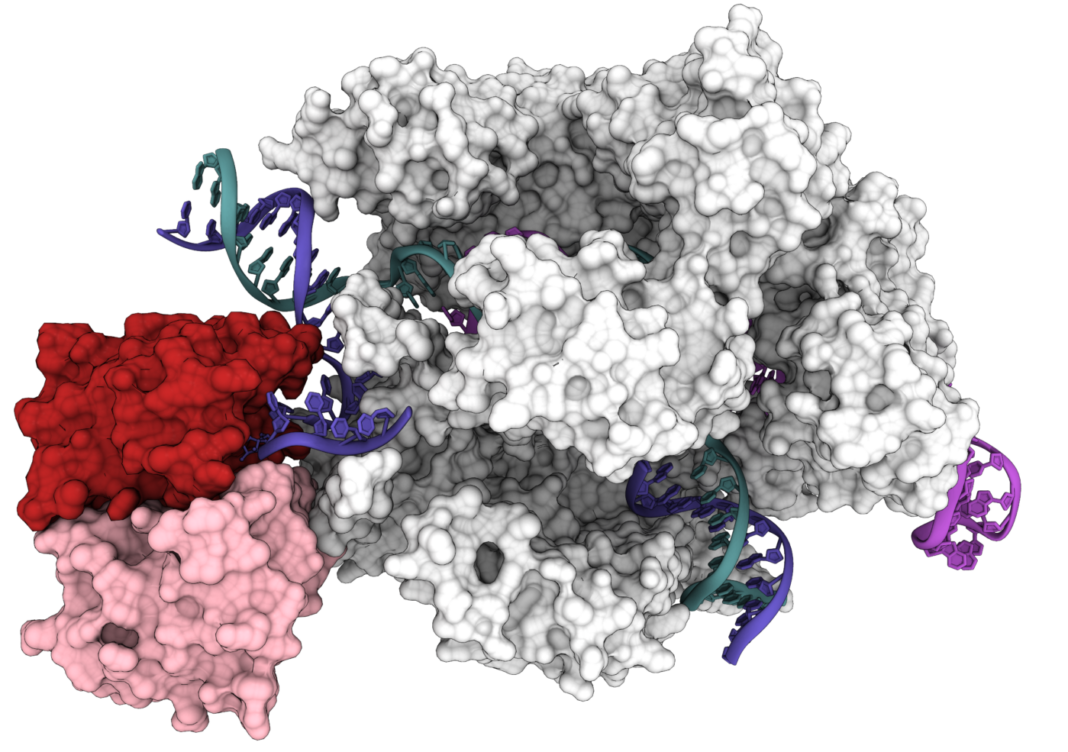

Now, researchers at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, have obtained the first 3D structure of base editors. More specifically, in order to understand the molecular basis for DNA adenosine deamination by adenine base editors (ABEs), they determined a 3.2-angstrom resolution cryo–EM structure of ABE8e in a substrate-bound state.

The research is published today in Science in the paper, “DNA capture by a CRISPR-Cas9–guided adenine base editor.” The detailed 3D structure provides a roadmap for tweaking base editors to make them more versatile and controllable for use in patients.

“We were able to observe for the first time a base editor in action,” said UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Gavin Knott, PhD. “Now we can understand not only when it works and when it doesn’t, but also design the next generation of base editors to make them even better and more clinically appropriate.

CRISPR-Cas9 base editors comprise RNA-guided Cas proteins fused to an enzyme that can deaminate a DNA nucleoside. “We actually see for the first time that base editors behave as two independent modules: You have the Cas9 module that gives you specificity, and then you have a catalytic module that provides you with the activity,” said Audrone Lapinaite, PhD, a former UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow who is now an assistant professor at Arizona State University in Tempe. “The structures we got of this base editor bound to its target really give us a way to think about Cas9 fusion proteins, in general, giving us ideas which region of Cas9 is more beneficial for fusing other proteins.”

The high resolution structure is of ABE8e bound to DNA in which the target adenine is replaced with an analog designed to trap the catalytic conformation. The structure, together with kinetic data comparing ABE8e to earlier ABEs, explains how ABE8e edits DNA bases and could inform future base-editor design.

Editing one base at a time

While the early adenine base editor was slow, the newest version—ABE8e—is blindingly fast: It completes nearly 100% of intended base edits in 15 minutes. Yet, ABE8e may be more prone to edit unintended pieces of DNA in a test tube, potentially creating off-target effects.

Activity assays showed why ABE8e is prone to create more off-target edits: The deaminase protein fused to Cas9 is always active. As Cas9 hops around the nucleus, it binds and releases hundreds or thousands of DNA segments before it finds its intended target. The attached deaminase doesn’t wait for a perfect match and often edits a base before Cas9 comes to rest on its final target.

The authors wrote that the kinetic and structural data “suggest that ABE8e catalyzes DNA deamination up to ~1100-fold faster than earlier ABEs because of mutations that stabilize DNA substrates in a constrained, transfer RNA–like conformation.” They continued, “ABE8e’s accelerated DNA deamination suggests a previously unobserved transient DNA melting that may occur during double-stranded DNA surveillance by CRISPR-Cas9.”

Knowing how the effector domain and Cas9 are linked can lead to a redesign that makes the enzyme active only when Cas9 has found its target.

“If you really want to design truly specific fusion protein, you have to find a way to make the catalytic domain more a part of Cas9, so that it would sense when Cas9 is on the correct target and only then get activated, instead of being active all the time,” Lapinaite said.

The structure of ABE8e also pinpoints two specific changes in the deaminase protein that make it work faster than the early version of the base editor, ABE7.10. Those two point mutations allow the protein to grip the DNA tighter and more efficiently replace A with G.

“As a structural biologist, I really want to look at a molecule and think about ways to rationally improve it. This structure and accompanying biochemistry really give us that power,” Knott added. “We can now make rational predications for how this system will behave in a cell, because we can see it and predict how it’s going to break or predict ways to make it better.”

ITALIANO

La capacità di CRISPR-Cas9 di tagliare e modificare il DNA è stata a lungo al centro della storia dell'editing del genoma. Ma i redattori di base guidati da CRISPR-Cas, che correggono in modo specifico una classe comune di sostituzioni di base senza scindere il DNA, sono recentemente entrati sotto i riflettori.

Nel 2016, David Liu, PhD, professore di chimica affiliato all'Università di Harvard, al Broad Institute e all'Howard Hughes Medical Institute, ha combinato Cas9 con un'altra proteina batterica per consentire la sostituzione precisa di un nucleotide con un altro: il primo editore base. Invece di tagliare, gli editor di base convertono i nucleotidi A • T in G • C, o C • G in T • A, in DNA per l'editing di precisione del genoma.

Ora, i ricercatori dell'Università della California (UC), Berkeley, hanno ottenuto la prima struttura 3D di editor di base. Più specificamente, al fine di comprendere le basi molecolari per la deaminazione dell'adenosina del DNA da parte degli editori di basi di adenina (ABE), hanno determinato una struttura crio-EM di risoluzione 3.2-angstrom di ABE8e in uno stato legato al substrato.

La ricerca è stata pubblicata oggi su Science nell'articolo, "Cattura del DNA da parte di un editore base di adenina guidato da CRISPR-Cas9". La struttura 3D dettagliata fornisce una tabella di marcia per modificare gli editor di base per renderli più versatili e controllabili per l'uso nei pazienti.

"Siamo stati in grado di osservare per la prima volta un editore di base in azione", ha detto Gavin Knott, dottorando del post dottorato della UC Berkeley. "Ora possiamo capire non solo quando funziona e quando non funziona, ma anche progettare la prossima generazione di editor di base per renderli ancora migliori e clinicamente appropriati.

Gli editor di base CRISPR-Cas9 comprendono proteine Cas guidate dall'RNA fuse in un enzima che può deaminare un nucleoside del DNA. "In realtà vediamo per la prima volta che gli editor di base si comportano come due moduli indipendenti: hai il modulo Cas9 che ti dà specificità e quindi hai un modulo catalitico che ti fornisce l'attività", ha detto Audrone Lapinaite, PhD, un ex Collaboratore post-dottorato della UC Berkeley che ora è professore assistente presso la Arizona State University di Tempe. "Le strutture che abbiamo di questo editor di base legato al suo obiettivo ci danno davvero un modo di pensare alle proteine di fusione Cas9, in generale, dandoci idee su quale regione di Cas9 è più vantaggiosa per fondere altre proteine."

La struttura ad alta risoluzione è di ABE8e legata al DNA in cui l'adenina bersaglio viene sostituita con un analogo progettato per intrappolare la conformazione catalitica. La struttura, insieme ai dati cinetici che confrontano ABE8e con ABE precedenti, spiega come ABE8e modifica le basi del DNA e potrebbe informare il futuro progetto dell'editor di base.

Modifica di una base alla volta

Mentre il primo editor di base dell'adenina era lento, la versione più recente, ABE8e, è incredibilmente veloce: completa quasi il 100% delle modifiche di base previste in 15 minuti. Tuttavia, ABE8e potrebbe essere più incline a modificare frammenti di DNA non intenzionali in una provetta, creando potenzialmente effetti fuori bersaglio.

I saggi di attività hanno dimostrato perché ABE8e è incline a creare più modifiche fuori target: la proteina deaminasi fusa con Cas9 è sempre attiva. Mentre Cas9 salta intorno al nucleo, si lega e rilascia centinaia o migliaia di segmenti di DNA prima di trovare il suo obiettivo previsto. La deaminase allegata non aspetta una corrispondenza perfetta e modifica spesso una base prima che Cas9 si fermi sul suo obiettivo finale.

Gli autori hanno scritto che i dati cinetici e strutturali "suggeriscono che ABE8e catalizza la deaminazione del DNA fino a ~ 1100 volte più velocemente delle ABE precedenti a causa di mutazioni che stabilizzano i substrati del DNA in una conformazione vincolata, simile all'RNA". Hanno continuato, "La deaminazione accelerata del DNA di ABE8e suggerisce una fusione del DNA transitorio in precedenza non osservata che può verificarsi durante la sorveglianza del DNA a doppio filamento da CRISPR-Cas9".

Sapere come sono collegati il dominio effector e Cas9 può portare a una riprogettazione che rende attivo l'enzima solo quando Cas9 ha trovato il suo obiettivo.

"Se vuoi davvero progettare proteine di fusione veramente specifiche, devi trovare un modo per rendere il dominio catalitico più una parte di Cas9, in modo che abbia senso quando Cas9 è sul bersaglio corretto e solo allora si attiva, invece di essere attivato sempre attivo ", ha detto Lapinaite.

La struttura di ABE8e individua anche due cambiamenti specifici nella proteina deaminasi che lo fanno funzionare più velocemente rispetto alla versione precedente dell'editor di base, ABE7.10. Queste mutazioni a due punti consentono alla proteina di afferrare il DNA più stretto e sostituire più efficacemente A con G.

“Come biologo strutturale, voglio davvero guardare una molecola e pensare ai modi per migliorarla razionalmente. Questa struttura e la biochimica di accompagnamento ci danno davvero quel potere ”, ha aggiunto Knott. "Ora possiamo fare previsioni razionali su come questo sistema si comporterà in una cellula, perché possiamo vederlo e prevedere come si romperà o prevedere i modi per migliorarlo".

Da:

Commenti

Posta un commento