1. CHE COS'È LA CRISPR?

Il nome corretto e completo è Crispr/Cas9: è una tecnica, precisa e potente, di correzione di uno o più geni in qualsiasi cellula. La tecnica Usa la collaborazione della Cas 9 e di una piccola molecola guida costituita da materiale genetico. La macchina molecolare così costruita si ispira a un sistema batterico chiamato Crispr presente in circa la metà dei batteri e nel 90% degli archea.

Crispr è l'acronimo di clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, una frase traducibile come brevi ripetizioni palindrome raggruppate e separate a intervalli regolari.

Cas9 è invece il nome della proteina associata a Crispr: insieme ad altre proteine simili fa parte di un sistema chiamato Crispr associated system.

In natura Crispr e Cas9 formano un complesso che funge da sistema immunitario per i batteri: tra una sequenza ripetuta e l'altra ci sono tratti di Dna che "archiviano" quelli di virus che hanno attaccato i batteri. Prendendo questi tratti come stampo, le proteine Cas attaccano i virus che contengono quel tratto di Dna e lo degradano.

2. COME FUNZIONA QUESTA TECNICA?

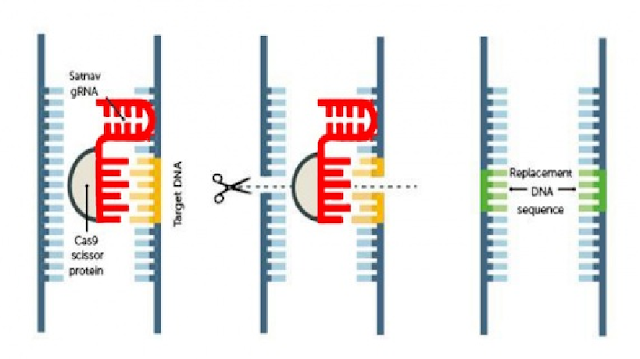

«Permette di esplorare qualsiasi Dna alla ricerca di particolari sequenze e di tagliarle», afferma Anna Meldolesi, biologa, autrice di E l'uomo creò l'uomo (Bollati Boringhieri, 2017) e di un sito sull'editing genomico, CRISPeR MANIA, sempre molto aggiornato sull'argomento. Le sequenze che si usano nella tecnica in vitro sono costituite da filamenti di Rna, "complementari" al Dna originale, che guidano le proteine alla sequenza bersaglio che si vuole modificare.

In questo modo si possono colpire e modificare tutti i geni che si vogliono, non solo quelli batterici: «Nelle mani dei ricercatori Crispr/Cas9 è diventato uno strumento multiuso, l'equivalente molecolare di un coltellino svizzero dotato di bussola per orientarsi lungo il Dna, di morsa per legarsi a esso, forbici per tagliare e altri accessori ancora», aggiunge Meldolesi.

La tecnica può essere utilizzata in molti modi. Insieme alla cancellazione di interi geni, può servire a introdurre nel genoma, in un punto preciso, un segmento del tutto estraneo. Oltre naturalmente a correggere i geni mutati in modo che tornino a funzionare bene.

3. CHE DIFFERENZA C'È TRA QUESTA TECNICA E QUELLA DEL

DNA RICOMBINANTE?

Sono state sperimentate nel tempo parecchie tecniche in grado di modificare il Dna di vari organismi, ma la maggior parte di esse era piuttosto grossolana e le modifiche ottenute non erano sempre quelle cercate o desiderate. Per rimediare alla presenza di un gene difettoso, un tempo si cercava semplicemente di aggiungerne uno "corretto" (Dna ricombinante).

Crispr è un metodo più preciso (ma non infallibile) per raggiungere un particolare gene, tagliarlo e quindi eliminarlo, oppure sostituirlo con un gene "giusto": è un'operazione di precisione, che consente di intervenire in modo mirato persino sulle singole lettere del Dna. La presenza nei batteri di altre proteine del sistema Cas fa pensare che la tecnica possa essere perfezionata e si possano aggiungere altre funzioni. «Come tecnologia è un work in progress, perché cambiando la proteina taglia-Dna e aggiustando la ricetta di base si stanno ottenendo risultati sempre migliori in termini di versatilità e precisione.»

4. QUALI SONO LE APPLICAZIONI ATTUALI DELLA CRIPR?

Per adesso i campi di applicazione sono tre: medicina, biologia e tecnologia. Crispr è usato per studiare per esempio la funzione di alcuni geni, eliminandoli dal genoma di una forma di vita e restando poi a vedere che cosa succede. Oppure per capire quali siano le parentele di gruppi di animali modificando il loro patrimonio genetico. Ma è servita anche, a livello pratico, per modificare lieviti in modo che producessero biocarburante, o per produrre organismi di interesse agricolo cambiando i geni con altri, considerati più utili, presi da varietà differenti.

Le applicazioni più lontane nel tempo - e ancora tutte da discutere - potrebbero essere quelle che riguardano la modifica dei geni umani nell'embrione, per eliminare eventuali difetti o favorire caratteristiche specifiche.

5. CI SONO OBIEZIONI ALL'USO DI QUESTA TECNOLOGIA?

Finora l'uso di questa tecnica nella modifica delle piante coltivate non ha sollevato particolari obiezioni. È invece verosimile che ce ne saranno, in futuro, quando si parlerà della possibilità di sperimentarla su animali domestici e d'allevamento: già oggi c'è chi si oppone anche a idee in apparenza positive, come il tentativo di modificare popolazioni di zanzare, vettrici di malattie, fino a farle scomparire. Questo perché, anche se si tratta di una specie ritenuta dannosa, qualsiasi modifica di un elemento dell'ecosistema può avere conseguenze inattese e negative.

Le preoccupazioni maggiori riguardano però l'editing degli embrioni umani, e per una ragione ben precisa. Se le modifiche genetiche sono effettuate su di un adulto, solo quella persona avrà il genoma modificato. Se invece a essere cambiato è il patrimonio genetico di un embrione, il futuro adulto potrà trasmettere le modifiche alla sua progenie: «Non abbiamo ancora le conoscenze sufficienti, né esiste un consenso sociale abbastanza ampio per poter compiere un passo del genere», commenta Meldolesi.

Alcuni ricercatori ed esperti di sicurezza hanno messo in guardia anche dalla relativa facilità ed economicità della tecnica rispetto a quelle precedenti: in mani sbagliate Crispr/Cas9 potrebbe essere utilizzata per scopi poco limpidi.

6. È PROPRIO COSÌ FACILE UTILIZZARE LA CRISPR?

«I componenti si possono ordinare online per qualche centinaio di euro e come tecnica è facile da maneggiare, molto più facile di altre», afferma Meldolesi. Non è però così facile usare Crispr/Cas9 nei garage, come facevano i ragazzi degli anni Settanta per costruire un computer. «Bisogna avere delle conoscenze di biologia e una minima abilità manuale», conclude. Un giornalista di Science, Jon Cohen, per esempio, ha voluto provare con mano se era vero che "qualunque idiota potesse riuscirci" e ha fallito miseramente.

7. CHI HA INVENTATO LA CRISPR/CAS9?

La scoperta del meccanismo immunitario dei batteri si deve a decenni di ricerche di biologia di base, come quelle che hanno appunto portato alla scoperta del "sistema immunitario" dei batteri. Quelle ricerche sono poi state perfezionate e ulteriormente sviluppate in alcuni laboratori statunitensi ed europei. Il punto cruciale è però l'applicazione della tecnica, che può dare origine a brevetti da cui i depositari potrebbero ricavare enormi somme di denaro.

A contendersi onori e brevetti sono principalmente due parti. Le prime ricercatrici a capire che il macchinario batterico poteva essere usato per fare il cosiddetto editing genetico sono state l'americana Jennifer Doudna e la francese Emmanuelle Charpentier. La tecnica è stata però adattata alle cellule umane dal cinese naturalizzato americano Feng Zhang: e il primo brevetto vero e proprio è stato ottenuto proprio da Zhang.

«Le due ricercatrici potrebbero vedersi attribuire una parte della torta successivamente», conclude Meldolesi, «e non si sa ancora chi vincerà la partita per il brevetto europeo.» E siccome la scienza sta trovando nuovi ingredienti e nuove ricette oltre a quella classica per far funzionare Crispr, lo scenario dei diritti di proprietà intellettuale sembra destinato a frammentarsi e complicarsi ulteriormente.

ENGLISH

1. WHAT IS CRISPR?

The correct and complete name is Crispr / Cas9: it is a precise and powerful technique for correcting one or more genes in any cell. The technique uses Cas 9's collaboration and a small guide molecule made up of genetic material. The molecular machine so constructed is inspired by a bacterial system called Crispr present in about half the bacteria and in 90% of the archea.

Crispr is the acronym for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, a phrase translatable as short palindrome repetitions grouped and separated at regular intervals.

Cas9 is the name of the protein associated with Crispr: along with other similar proteins is part of a system called Crispr associated system.

Crispr and Cas9 naturally form a complex that acts as an immune system for bacteria. Between a repeating sequence and the other there are DNA traits that "archive" those of viruses that have attacked the bacteria. Taking these traits as a mold, Cas proteins attack viruses that contain that trait of DNA and degrade it.

2. HOW DOES IT WORK?

"It allows exploring any DNA in search of particular sequences and cutting them down," says Anna Meldolesi, biologist, author of A Man Created Man (Bollati Boringhieri, 2017) and a site on genomic editing, CRISPeR MANIA, Always very up to date on the subject. The sequences used in the in vitro technique are made up of RNA filaments, "complementary" to the original DNA that guides the protein to the target sequence that you want to modify.

In this way, all the genes that they want, not just the bacteria, can be hit and modified: "Crispr / Cas9 researchers have become a multipurpose tool, the molecular equivalent of a Swiss knife equipped with a compass to navigate along the DNA , A vice to tie it up, scissors to cut and other accessories, "adds Meldolesi.

The technique can be used in many ways. Along with the deletion of entire genes, it may serve to introduce a totally strange segment into the genome. Besides naturally correcting mutated genes so they get back to work well.

3. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THIS TECHNIQUE AND

RECOMBINANT DNA?

Several techniques have been experimented over time to modify the DNA of various organisms, but most of them were rather coarse and the modifications obtained were not always the ones sought or desired. To remedy the presence of a defective gene, one was simply trying to add a "correct" (recombinant DNA).

Crispr is a more precise (but not infallible) method to reach a particular gene, cut it and then eliminate it, or replace it with a "right" gene: it is a precision operation that allows you to intervene even on individual letters dNA. The presence in the bacteria of other Cas system proteins suggests that the technique can be refined and other functions can be added. "Technology is a work in progress, because changing the DNA-size protein and adjusting the basic recipe is getting better results in terms of versatility and precision.

4. WHAT ARE CURRENT APPLICATIONS OF CRISPR?

For now the fields of application are three: medicine, biology and technology. Crispr is used to study, for example, the function of some genes, eliminating them from the genome of a lifestyle and then seeing what happens. Or to understand the kinship of animal groups by altering their genetic heritage. But it was also practically used to modify yeasts so that they produce biofuels, or to produce organisms of agricultural interest by changing genes to others, considered more useful, taken from different varieties.

Farthest applications over time - and still all to be discussed - could be the ones that affect the modification of human genes in the embryo to eliminate any defects or favor specific features.

5. WHAT ARE OBJECTIONS FOR THE USE OF THIS TECHNOLOGY?

So far the use of this technique in modification of cultivated plants has not raised any particular objections. It is likely that there will be, in the future, when it comes to the possibility of experimenting with domestic animals and breeding: today there are those who are also opposed to seemingly positive ideas, such as attempting to modify mosquito populations, Carriers of diseases, until they disappear. This is because, even if it is a harmful species, any modification of an ecosystem element can have unexpected and negative consequences.

The major concerns, however, concern the editing of human embryos, and for a very precise reason. If genetic modifications are made on an adult, only that person will have the modified genome. If instead the genetic heritage of an embryo is changed, the adult future will be able to convey changes to his offspring: "We do not have enough knowledge yet, and there is not enough broad consensus for such a step," comments Meldolesi .

Some researchers and security experts have also warned about the relative ease and cost-effectiveness of the technique compared to the previous ones: Crispr / Cas9 could be used for unclear purposes.

6. IS IT SO EASY TO USE CRISPR?

"Components can be ordered online for a few hundred euros and as a technique is easy to handle, much easier than others," says Meldolesi. However, it is not easy to use Crispr / Cas9 in the garage, as did the guys from the seventies to build a computer. "We need to have knowledge of biology and a minimal manual skill," he concludes. A Science journalist, Jon Cohen, for example, wanted to try out with a hand if it was true that "any idiot could do it" and failed miserably.

7. WHO HAVE INVENTED CRISPR / CAS9?

The discovery of the immune mechanism of bacteria is due to decades of basic biology research, such as those that have led to the discovery of the "immune system" of bacteria. Those researches have been further refined and further developed in some US and European laboratories. The crucial point is, however, the application of the technique, which can give rise to patents from which the depositors could derive enormous sums of money.

Honors and patents are mainly two parts. The first researchers to understand that bacterial equipment could be used to make genetic editing were American Jennifer Doudna and French Emmanuelle Charpentier. However, the technique has been adapted to human cells by Chinese nationalized Feng Zhang: and the first patent was actually obtained by Zhang.

"The two researchers may be able to attribute part of the cake later," concludes Meldolesi, "and no one yet knows who will win the game for the European patent." And as science is finding new ingredients and new recipes besides the classic one Crispr works, the scenario of intellectual property rights seems destined to fragment and complicate further.

Da:

http://www.focus.it/scienza/scienze/editing-del-genoma-7-domande-sulla-tecnica-crispr

Commenti

Posta un commento