Immune Response Insights against Fungal Pathogen Candida Auris / Analisi della risposta immunitaria contro il patogeno fungino Candida Auris

Immune Response Insights against Fungal Pathogen Candida Auris / Analisi della risposta immunitaria contro il patogeno fungino Candida Auris

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

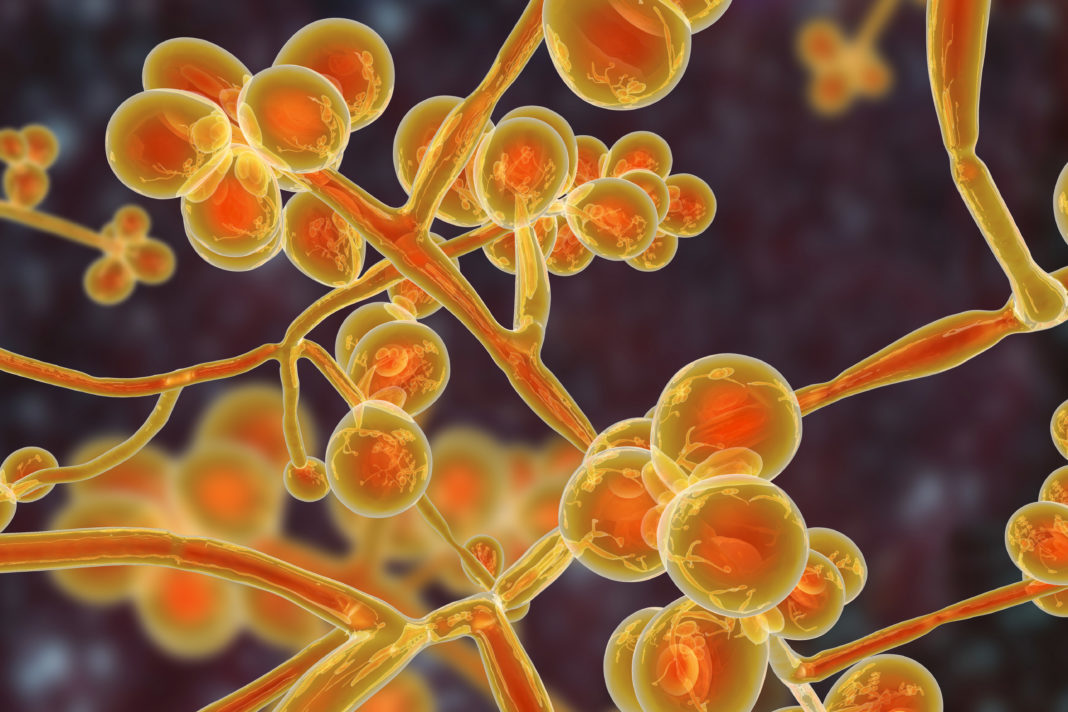

Candida auris emerged as an important fungal pathogen in 2009, when the previously unknown fungus was discovered in the infected ear of a seventy-year-old Japanese woman. Where C. auris suddenly came from was not clear, but soon after that, different strains appeared all over the world. It turned out to be a persistent, difficult to control fungus.

Since then, the fungus has spread across six continents as a causative microorganism of hospital-acquired infections. It remains challenging on many fronts, not only difficult to diagnose but also resistant to many commonly used antifungal drugs.

Now, an international team led by researchers from Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands, has discovered that the human immune system recognizes the fungus well. The team integrated transcriptional and functional immune-cell profiling to uncover innate defense mechanisms against C. auris.

The work is published in an article in Nature Microbiology titled, “Transcriptional and functional insights into the host immune response against the emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris.”

“We started to investigate C. auris with international colleagues because there was virtually nothing known about this fungus,” said Mariolina Bruno, a PhD candidate in the Radboud University Medical Center’s department of internal medicine. Their findings showed, according to Bruno, that, “A well-functioning immune system recognizes the fungus clearly and can control it well.” But, the fungus is especially dangerous for people with compromised immunity.

A careful study of the human immune response to the C. auris infection demonstrated that specific components of the cell wall of the fungus play an essential role in this recognition. David Williams, PhD, the Carroll H. Long chair of excellence for surgical research at East Tennessee State University said: “These are unique structures that you do not encounter with other fungi. Those specific chemical structures stimulate the immune system enough to take action and clear the fungus.”

The authors write that C. auris induces “a specific transcriptome in human mononuclear cells, a stronger cytokine response compared with Candida albicans, but a lower macrophage lysis capacity.”

They noted that C. auris-induced innate immune activation is “mediated through the recognition of C-type lectin receptors, mainly elicited by structurally unique C. auris mannoproteins.”

The fact that C. auris is considered a serious and emerging infectious disease is mainly due to its resistance to many disinfectants and fungicides. People with an invasive C. auris fungal infection have a thirty to sixty percent chance of dying, precisely because of the immunity of the fungus to many fungicides. Alistair Brown, PhD, professor at the MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, University of Exeter, noted that, “Our research not only shows that these cell wall components are important for the detection by the immune system, but also that they are indispensable to the fungus. Drugs that selectively block the production and operation of these components are currently being investigated for safety and effectiveness. Perhaps one of these is the ideal candidate to tackle the fungus.”

Since these cell wall components are indispensable to C. auris, the risk of resistance to such a new drug is small. In order to develop resistance, the fungus must at least remain alive so that it can gradually adapt to the new drug.

Candida auris is related to the much better-known Candida albicans, which can cause vaginal fungal infections. In the study, C. albicans has therefore served as comparison material. Bruno noted that, “On the one hand, we see that C auris evokes a better immunity reaction than C. albicans. On the other hand, C. auris appears less pathogenic, but once in the bloodstream, both fungi are usually life-threatening.”

What makes the problem even worse is that C. auris is not so easy to identify. This makes it easy to confuse with other fungi, which can lead to a delay in treatment. Jacques Meis, MD, PhD, consultant, clinical microbiology and infectious diseases, Canisius-Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen said, “You should determine the fungi type on a molecular level, enabling you to immediately see which fungus you are dealing with, but not every laboratory has the facilities for that.” Earlier this year, he and Paul Verweij, MD, professor of clinical mycology at Radboud University Medical Center, called for the nation-wide monitoring of serious fungal infections to gain a better understanding of the burden of disease and mortality rates.

The team’s findings suggest that, in vivo experimental models of disseminated candidiasis, “C. auris was less virulent than C. albicans.” Collectively, the authors noted, “These results demonstrate that C. auris is a strong inducer of innate host defense, and identify possible targets for adjuvant immunotherapy.”

The question why C. auris suddenly appeared in 2009 has still not been answered. The fungus was not found in stored patient material from previous years, so it seems to be a new or mutated fungus. It has been hypothesized that the increase in temperatures caused by global warming may play a role.

“An interesting point of view,” said Bruno, “but without further evidence, it is as yet highly speculative. Apart from the actual origin history or ‘birth’ of C. auris, the article in Nature Microbiology provides information on how the interaction between humans and the fungus C. auris occurs: how the fungus stimulates the immune system, what C. auris‘ pharmacological Achilles heel is, and what the opportunities for immunotherapy are.”

ITALIANO

La Candida auris è emersa come un importante patogeno fungino nel 2009, quando il fungo precedentemente sconosciuto è stato scoperto nell'orecchio infetto di una donna giapponese di settant'anni. Non era chiaro da dove provenisse C. auris, ma subito dopo apparvero diversi ceppi in tutto il mondo. Si è rivelato un fungo persistente e difficile da controllare.

Da allora, il fungo si è diffuso in sei continenti come microrganismo responsabile delle infezioni contratte in ospedale. Rimane impegnativo su molti fronti, non solo difficile da diagnosticare ma anche resistente a molti farmaci antifungini comunemente usati.

Ora, un gruppo internazionale guidato da ricercatori del Radboud University Medical Center nei Paesi Bassi, ha scoperto che il sistema immunitario umano riconosce bene il fungo. Il gruppo ha integrato la profilazione trascrizionale e funzionale delle cellule immunitarie per scoprire meccanismi di difesa innati contro C. auris.

Il lavoro è pubblicato in un articolo su Nature Microbiology intitolato "Insights trascrizionali e funzionali nella risposta immunitaria dell'ospite contro il patogeno fungino emergente Candida auris".

"Abbiamo iniziato a indagare su C. auris con colleghi internazionali perché non si sapeva praticamente nulla di questo fungo", ha detto Mariolina Bruno, dottoranda presso il dipartimento di medicina interna del Radboud University Medical Center. Le loro scoperte hanno mostrato, secondo Bruno, che "un sistema immunitario ben funzionante riconosce chiaramente il fungo e può controllarlo bene". Ma il fungo è particolarmente pericoloso per le persone con un'immunità compromessa.

Un attento studio della risposta immunitaria umana all'infezione da C. auris ha dimostrato che componenti specifici della parete cellulare del fungo giocano un ruolo essenziale in questo riconoscimento. David Williams, PhD, la cattedra di eccellenza Carroll H. Long per la ricerca chirurgica presso la East Tennessee State University ha dichiarato: “Queste sono strutture uniche che non si incontrano con altri funghi. Quelle specifiche strutture chimiche stimolano il sistema immunitario abbastanza da agire e eliminare il fungo ".

Gli autori scrivono che C. auris induce "un trascrittoma specifico nelle cellule mononucleate umane, una risposta delle citochine più forte rispetto alla Candida albicans, ma una capacità di lisi dei macrofagi inferiore".

Hanno notato che l'attivazione immunitaria innata indotta da C. auris è "mediata dal riconoscimento dei recettori della lectina di tipo C, principalmente indotta da mannoproteine di C. auris strutturalmente uniche".

Il fatto che C. auris sia considerata una malattia infettiva grave ed emergente è principalmente dovuto alla sua resistenza a molti disinfettanti e fungicidi. Le persone con un'infezione fungina invasiva da C. auris hanno una probabilità dal trenta al sessanta per cento di morire, proprio a causa dell'immunità del fungo a molti fungicidi. Alistair Brown, PhD, professore presso l'MRC Center for Medical Mycology, Università di Exeter, ha osservato che, "La nostra ricerca non solo mostra che questi componenti della parete cellulare sono importanti per il rilevamento da parte del sistema immunitario, ma anche che sono indispensabili per il fungo. I farmaci che bloccano selettivamente la produzione e il funzionamento di questi componenti sono attualmente oggetto di indagine in termini di sicurezza ed efficacia. Forse uno di questi è il candidato ideale per affrontare il fungo ".

Poiché questi componenti della parete cellulare sono indispensabili per C. auris, il rischio di resistenza a un tale nuovo farmaco è basso. Per sviluppare la resistenza, il fungo deve almeno rimanere in vita in modo che possa adattarsi gradualmente al nuovo farmaco.

La Candida auris è correlata alla ben più nota Candida albicans, che può causare infezioni fungine vaginali. Nello studio, C. albicans è quindi servito come materiale di confronto. Bruno ha osservato che: “Da un lato, vediamo che la C auris evoca una reazione immunitaria migliore di C. albicans. D'altra parte, C. auris sembra meno patogeno, ma una volta nel flusso sanguigno, entrambi i funghi sono solitamente pericolosi per la vita ".

Ciò che rende il problema ancora peggiore è che C. auris non è così facile da identificare. Questo lo rende facile da confondere con altri funghi, il che può portare a un ritardo nel trattamento. Jacques Meis, MD, PhD, consulente, microbiologia clinica e malattie infettive, Ospedale Canisius-Wilhelmina, Nijmegen, ha dichiarato: "Dovresti determinare il tipo di fungo a livello molecolare, permettendoti di vedere immediatamente con quale fungo hai a che fare, ma non tutti i laboratori hano le strutture per questo. " All'inizio di quest'anno, lui e Paul Verweij, MD, professore di micologia clinica presso il Radboud University Medical Center, hanno chiesto il monitoraggio a livello nazionale delle infezioni fungine gravi per ottenere una migliore comprensione del peso delle malattie e dei tassi di mortalità.

I risultati del gruppo suggeriscono che, in base a modelli sperimentali in vivo di candidosi disseminata, "C. auris era meno virulenta di C. albicans. " Collettivamente, gli autori hanno osservato: "Questi risultati dimostrano che C. auris è un forte induttore della difesa innata dell'ospite e identificano possibili bersagli per l'immunoterapia adiuvante".

La domanda sul perché C. auris è apparsa improvvisamente nel 2009 non ha ancora avuto risposta. Il fungo non è stato trovato nel materiale del paziente conservato negli anni precedenti, quindi sembra essere un fungo nuovo o mutato. È stato ipotizzato che l'aumento delle temperature causato dal riscaldamento globale possa avere un ruolo.

“Un punto di vista interessante”, ha detto Bruno, “ma senza ulteriori prove, è ancora altamente speculativo. Oltre all'effettiva storia dell'origine o 'nascita' di C. auris, l'articolo su Nature Microbiology fornisce informazioni su come avviene l'interazione tra l'uomo e il fungo C. auris: come il fungo stimola il sistema immunitario, cosa è dal punto di vista farmacologico il tallone d'Achille di C. auris e quali sono le opportunità per l'immunoterapia ".

Da:

Commenti

Posta un commento