Herpes: ecco come si insedia nelle cellule nervose / Herpes: this is how it settles in nerve cells

Herpes: ecco come si insedia nelle cellule nervose / Herpes: this is how it settles in nerve cells

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

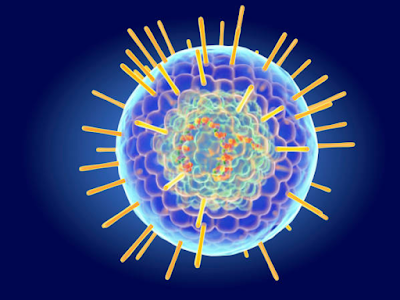

Circa 3,7 miliardi di persone – due terzi della popolazione mondiale sotto i 50 anni – ha l’herpes simplex di tipo 1, secondo i dati dell’Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità. Questo patogeno è responsabile dell’herpes labiale ed in misura minore di quello genitale e di altre manifestazioni cliniche. Anche una volta risolti i sintomi, questi possono ripresentarsi in più occasioni. Questo accade perché il virus permane nel nostro organismo per tutta la vita e si nasconde in alcune strutture del sistema nervoso periferico. Oggi un gruppo della Northwestern University ha scoperto in che modo l’herpes si annida in queste cellule. I risultati, pubblicati su Nature, indicano una strada da percorrere per la ricerca di un vaccino.

Trovare un vaccino contro l’herpes

L’herpes simplex 1 causa solitamente sintomi fastidiosi ma lievi, come vesciche e piaghe dolorose all’esterno o all’interno della bocca e meno frequentemente a livello genitale e anale. In rari casi i pazienti possono sviluppare complicanze gravi, come encefaliti e patologie dell’occhio. In generale, una volta entrato nel nostro corpo, il virus rimane silente e non può essere eradicato. Per questo, da tempo gli scienziati cercano un vaccino contro l‘herpes simplex 1 e 2 (il tipo 2 è causa dell’herpes genitale). La ricerca odierna studia in profondità cosa succede ai tessuti e come il patogeno sfrutta alcuni componenti per insediarsi nei gangli nervosi, piccoli centri nervosi dislocati a livello periferico.

Il viaggio dell’herpes nelle cellule

I ricercatori hanno scoperto che l’herpes si appoggia e sfrutta l’azione di una proteina che, come un disertore, si allea con il patogeno e lo aiuta a penetrare. Il processo viene chiamato “assimilazione”. Ripartiamo dall’inizio. L’obiettivo del patogeno è arrivare al nucleo della cellula, in questo caso di quella nervosa. Come altri virus, salta su particolari strutture all’interno della cellula, dette microtubuli e simili a binari del treno. Per riuscire a spostarsi sui binari, l’herpes sfrutta due proteine, centrali per queste strutture, la dineina e la chinesina. Queste sono come due motori che spostano il treno in direzioni diverse, la dineina verso il centro della città (il nucleo della cellula) e la chinesina verso la periferia.

Dalla periferia al centro, con un treno veloce

Nel caso di un virus influenzale che deve penetrare le cellule epiteliali della mucosa il viaggio avviene all’interno di una piccola città ed è abbastanza breve. Per questo, anche se il patogeno si sposta in due direzioni, raggiunge comunque il centro piuttosto rapidamente. Il tragitto per raggiungere il nucleo delle cellule nervose, invece, è più lungo e articolato, come quello all’interno di una grande nazione. Senza “aiuti”, l’herpes rischierebbe di rimanere sempre in periferia e di non riuscire ad arrivare. Per questo il virus cerca e trova nella chinesina un alleato che abbrevia il percorso. Questa, infatti, traghetta il virus direttamente al nucleo. Per farla molto breve, il virus “chiede” il passaggio a una proteina e lo ottiene.

Spezzare il collegamento

“Siamo entusiasti – commenta Greg Smith, docente di microbiologia ed immunologia alla Northwestern University – di scoprire più in profondità i meccanismi molecolari che questi virus hanno sviluppato e che li rendono probabilmente i patogeni di maggior successo conosciuti dalla scienza”. Comprendere il meccanismo è essenziale per interrompere il viaggio dell’herpes. “Se riuscissimo a fermare l’assimilazione della chinesina”, sottolinea Smith, “avremmo un virus che non è in grado di infettare il sistema nervoso. E poi si avrebbe un candidato per un vaccino preventivo. Abbiamo un disperato bisogno di questo vaccino”.

ENGLISH

About 3.7 billion people - two thirds of the world's population under the age of 50 - have type 1 herpes simplex, according to data from the World Health Organization. This pathogen is responsible for cold sores and to a lesser extent for genital herpes and other clinical manifestations. Even after the symptoms have resolved, they can recur on multiple occasions. This happens because the virus remains in our body for life and hides in some structures of the peripheral nervous system. Today a group from Northwestern University discovered how herpes lurks in these cells. The results, published in Nature, indicate a way forward in the search for a vaccine.

Finding a herpes vaccine

Herpes simplex 1 usually causes annoying but mild symptoms, such as painful blisters and sores outside or inside the mouth and less frequently at the genital and anal level. In rare cases, patients can develop serious complications, such as encephalitis and eye diseases. In general, once it enters our body, the virus remains silent and cannot be eradicated. For this reason, scientists have long been looking for a vaccine against herpes simplex 1 and 2 (type 2 is the cause of genital herpes). Today's research studies in depth what happens to the tissues and how the pathogen uses some components to settle in the nerve ganglia, small nerve centers located at the peripheral level.

The journey of herpes into cells

Researchers have discovered that herpes relies on and exploits the action of a protein which, like a defector, allies itself with the pathogen and helps it to penetrate. The process is called "assimilation". Let's start from the beginning. The pathogen's goal is to reach the cell nucleus, in this case the nerve cell. Like other viruses, it jumps on particular structures inside the cell, called microtubules and similar to train tracks. To be able to move on the tracks, herpes uses two proteins, central to these structures, dynein and kinesin. These are like two engines that move the train in different directions, the dynine towards the city center (the nucleus of the cell) and the kinesin towards the periphery.

From the suburbs to the center, with a fast train

In the case of an influenza virus that must penetrate the epithelial cells of the mucosa, the journey takes place within a small town and is quite short. Therefore, even if the pathogen moves in two directions, it still reaches the center rather quickly. The journey to reach the nucleus of nerve cells, on the other hand, is longer and more complex, like that within a great nation. Without "help", herpes would risk staying on the outskirts all the time and not being able to get there. For this reason the virus seeks and finds in kinesin an ally that shortens the path. This, in fact, ferries the virus directly to the nucleus. In short, the virus "asks" for a switch to a protein and gets it.

Break the link

"We are excited - comments Greg Smith, professor of microbiology and immunology at Northwestern University - to discover more in depth the molecular mechanisms that these viruses have developed and which make them probably the most successful pathogens known to science". Understanding the mechanism is essential to stop the herpes journey. "If we could stop the assimilation of kinesin," Smith points out, "we would have a virus that is unable to infect the nervous system. And then you would have a candidate for a preventive vaccine. We desperately need this vaccine ”.

Da:

https://www.galileonet.it/viaggio-herpes-cellule-nervose/?utm_source=mailpoet&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=variante+africana+coronavirus

Commenti

Posta un commento