Il rivoluzionario microscopio a raggi X rivela le onde sonore nelle profondità dei cristalli / Revolutionary X-ray microscope unveils sound waves deep within crystals

Il rivoluzionario microscopio a raggi X rivela le onde sonore nelle profondità dei cristalli. Il procedimento del brevetto ENEA RM2012A000637 è molto utile in questo tipo di applicazione. / Revolutionary X-ray microscope unveils sound waves deep within crystals. The process of the ENEA patent RM2012A000637 is very useful in this type of application.

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

Gli scienziati hanno sviluppato una tecnologia innovativa che consente loro di vedere le onde sonore ed i difetti microscopici all'interno dei cristalli, promettendo intuizioni che collegano il movimento atomico ultraveloce a comportamenti macroscopici su larga scala.

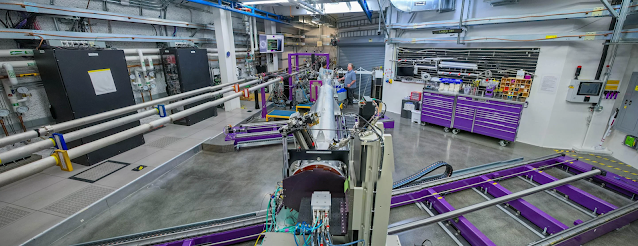

Ricercatori del Laboratorio Nazionale dell'Acceleratore SLAC del Dipartimento di Energia. La Stanford University e la Denmark Technical University hanno progettato un microscopio a raggi X all'avanguardia in grado di osservare direttamente le onde sonore su scala più piccola: il livello del reticolo all'interno di un cristallo.

Questi risultati, pubblicati la scorsa settimana su Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , potrebbero cambiare il modo in cui gli scienziati studiano i cambiamenti ultraveloci nei materiali e le proprietà che ne derivano.

"La struttura atomica dei materiali cristallini dà origine alle loro proprietà ed ai relativi 'casi d'uso' per un'applicazione", ha affermato una delle ricercatrici, Leora Dresselhaus-Marais, assistente professore a Stanford e SLAC. “I difetti cristallini e gli spostamenti su scala atomica descrivono il motivo per cui alcuni materiali si rafforzano mentre altri si frantumano in risposta alla stessa forza. I fabbri e la produzione di semiconduttori hanno perfezionato la nostra capacità di controllare alcuni tipi di difetti, tuttavia, poche tecniche oggi possono immaginare queste dinamiche in tempo reale su scala appropriata per risolvere il modo in cui le distorsioni si collegano alle proprietà generali”.

In questo nuovo lavoro, il gruppo ha generato onde sonore in un cristallo di diamante, quindi ha utilizzato il nuovo microscopio a raggi X sviluppato per visualizzare direttamente le sottili distorsioni all’interno del reticolo cristallino. Lo hanno fatto nei tempi in cui queste vibrazioni su scala atomica si verificano naturalmente, sfruttando gli impulsi ultraveloci ed ultraluminosi disponibili presso la sorgente di luce coerente Linac (LCLS) di SLAC.

I ricercatori hanno posizionato una speciale lente a raggi X lungo il raggio diffratto dal reticolo cristallino per filtrare la porzione “perfettamente compattata” del cristallo ed individuare le distorsioni nella struttura del cristallo causate dall'onda sonora e dai difetti.

"Lo abbiamo usato per immaginare come un laser ultraveloce trasferisce la sua energia luminosa in calore attraverso riflessioni successive dell'onda sonora fuori equilibrio dalla superficie anteriore e posteriore del cristallo." Dresselhaus-Marais ha detto. “Mostrandolo nel diamante – un cristallo con la velocità del suono più elevata – illustriamo le nuove opportunità ora disponibili con il nostro microscopio per studiare nuovi fenomeni nel profondo dei cristalli”.

I risultati identificano un modo per vedere cambiamenti superveloci nei materiali senza danneggiarli. Prima di questa scoperta, gli strumenti utilizzati dai ricercatori erano troppo lenti per vedere questi cambiamenti. Ciò è importante perché molte cose, come il modo in cui il calore si muove o il modo in cui si diffondono le onde sonore, dipendono da questi rapidi cambiamenti.

Le implicazioni di questa svolta si estendono a varie discipline, dalla scienza dei materiali alla fisica, e si estendono anche a campi come la geologia e l’industria manifatturiera. Comprendendo i cambiamenti a livello atomico che portano a eventi osservabili più ampi nei materiali, gli scienziati possono ottenere un quadro più chiaro delle trasformazioni, dei processi di fusione e delle reazioni chimiche nei materiali, accedendo a nuovi 13 ordini di grandezza di scale temporali.

“Questo nuovo strumento ci offre un’opportunità unica per studiare come eventi rari causati da difetti, distorsioni atomiche od altri stimoli localizzati all’interno di un reticolo danno origine a cambiamenti macroscopici nei materiali”, ha affermato Dresselhaus-Marais. “Anche se la nostra comprensione dei cambiamenti macroscopici nei materiali è piuttosto avanzata, spesso ci mancano i dettagli di quali “eventi istigatori” alla fine causano le trasformazioni di fase, la fusione o la chimica che osserviamo su scala più ampia. Con tempi ultrabrevi ora a portata di mano, abbiamo la capacità di ricercare questi eventi rari alle loro scale temporali native”.

LCLS è una struttura utente del DOE Office of Science. Questa ricerca è stata supportata dall'Office of Science (BES).

ENGLISH

Scientists have developed innovative technology that allows them to see sound waves and microscopic defects inside crystals, promising insights that link ultrafast atomic motion to large-scale macroscopic behavior.

Researchers from the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Stanford University and Denmark Technical University have designed a cutting-edge X-ray microscope that can directly observe sound waves at the smallest scale: the grating level inside a crystal.

These findings, published last week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could change the way scientists study ultrafast changes in materials and the resulting properties.

“The atomic structure of crystalline materials gives rise to their properties and related 'use cases' for an application,” said one of the researchers, Leora Dresselhaus-Marais, an assistant professor at Stanford and SLAC. “Crystalline defects and atomic-scale shifts describe why some materials strengthen while others shatter in response to the same force. Semiconductor manufacturing and manufacturing have perfected our ability to control certain types of defects, however, few techniques today can image these dynamics in real time at the appropriate scale to resolve how distortions relate to overall properties.”

In this new work, the team generated sound waves in a diamond crystal, then used their newly developed X-ray microscope to directly image subtle distortions within the crystal lattice. They did this in the times when these atomic-scale vibrations occur naturally, taking advantage of the ultrafast, ultraluminous pulses available at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS).

The researchers positioned a special X-ray lens along the diffracted beam from the crystal lattice to filter out the “perfectly packed” portion of the crystal and identify distortions in the crystal structure caused by the sound wave and defects.

“We used it to imagine how an ultrafast laser transfers its light energy into heat through successive reflections of the out-of-equilibrium sound wave from the front and back surfaces of the crystal.” Dresselhaus-Marais said. “By showing this in diamond – a crystal with the fastest speed of sound – we illustrate the new opportunities now available with our microscope to study new phenomena deep inside crystals.”

The findings identify a way to see superfast changes in materials without damaging them. Before this discovery, the tools researchers used were too slow to see these changes. This is important because many things, such as how heat moves or how sound waves spread, depend on these rapid changes.

The implications of this breakthrough extend across disciplines, from materials science to physics, and also extend to fields such as geology and manufacturing. By understanding atomic-level changes that lead to broader observable events in materials, scientists can gain a clearer picture of transformations, melting processes and chemical reactions in materials, accessing 13 new orders of magnitude time scales.

“This new tool gives us a unique opportunity to study how rare events caused by defects, atomic distortions, or other localized stimuli within a lattice give rise to macroscopic changes in materials,” said Dresselhaus-Marais. “Although our understanding of macroscopic changes in materials is quite advanced, we often lack the details of which “instigating events” ultimately cause the phase transformations, melting, or chemistry we observe on a larger scale. With ultrashort timescales now at hand, we have the ability to search for these rare events at their native timescales.”

LCLS is a user facility of the DOE Office of Science. This research was supported by the Office of Science (BES).

Da:

https://www6.slac.stanford.edu/news/2023-09-28-revolutionary-x-ray-microscope-unveils-sound-waves-deep-within-crystals?fbclid=IwAR3kfQ7goVh78Hm7DW6FnSvjIyjCSh-ufH32hNKjdUOHmHRoL1q84zxaJ7A

Commenti

Posta un commento