Come le malattie di origine alimentare proteggono il sistema nervoso dell'intestino / How foodborne diseases protect the gut's nervous system

Come le malattie di origine alimentare proteggono il sistema nervoso dell'intestino / How foodborne diseases protect the gut's nervous system

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

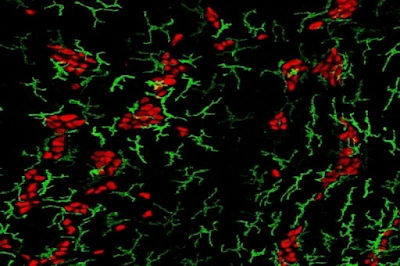

Macrofagi (verde) che circondano i neuroni enterici

(rosso). / Macrophages (green) surrounding

enteric neurons (red). / Credito: Laboratorio di

immunologia delle mucose presso la Rockefeller

University

Un semplice insetto intestinale potrebbe fare molti

danni. Ci sono 100 milioni di neuroni sparsi lungo

il tratto gastrointestinale, direttamente sulla linea di

fuoco, che possono essere eliminati dalle infezioni

intestinali, portando potenzialmente a malattie

gastrointestinali a lungo termine.

Ma potrebbe esserci un vantaggio nell'infezione enterica. Un nuovo studio ha scoperto che i topi infettati da batteri o parassiti sviluppano una forma unica di tolleranza abbastanza diversa dalla risposta immunitaria dei libri di testo. La ricerca, pubblicata su Cell , descrive come i macrofagi intestinali rispondono a un precedente insulto schermando i neuroni enterici , impedendo loro di morire quando i futuri agenti patogeni colpiscono. Questi risultati potrebbero in definitiva avere implicazioni cliniche per condizioni come la sindrome dell'intestino irritabile, che sono state collegate alla morte incontrollata dei neuroni intestinali.

"Stiamo descrivendo una sorta di memoria innata che persiste dopo che l'infezione primaria è scomparsa", afferma Daniel Mucida di Rockefeller. "Questa tolleranza non esiste per uccidere futuri agenti patogeni, ma per affrontare il danno che l'infezione provoca, preservando il numero di neuroni nell'intestino".

Causa di morte neuronale

Conosciuto come il "secondo cervello" del corpo, il sistema nervoso enterico ospita il più grande deposito di neuroni e glia al di fuori del cervello stesso. Il sistema nervoso del tratto gastrointestinale esiste più o meno autonomamente, senza input significativi dal cervello. Controlla il movimento dei nutrienti e dei rifiuti per via fiat, coordinando lo scambio di liquidi locali e il flusso sanguigno con un'autorità che non si vede da nessun'altra parte nel sistema nervoso periferico.

Se un numero sufficiente di quei neuroni muore, il tratto gastrointestinale perde il controllo.

Mucida e colleghi hanno riferito l'anno scorso che le infezioni intestinali nei topi possono uccidere i neuroni enterici dei roditori, con conseguenze disastrose per la motilità intestinale. All'epoca, i ricercatori hanno notato che i sintomi dell'IBS rispecchiano da vicino ciò che ci si potrebbe aspettare di vedere quando i neuroni enterici muoiono in massa, aumentando la possibilità che infezioni intestinali minori potrebbero decimare i neuroni enterici in alcune persone più di altre, portando alla stitichezza e altre condizioni GI inspiegabili.

I ricercatori si sono chiesti se il corpo ha qualche meccanismo per prevenire la perdita neuronale dopo l'infezione. In lavori precedenti, il laboratorio aveva infatti dimostrato che i macrofagi nell'intestino producono molecole specializzate che impediscono ai neuroni di morire in risposta allo stress.

Ma potrebbe esserci un vantaggio nell'infezione enterica. Un nuovo studio ha scoperto che i topi infettati da batteri o parassiti sviluppano una forma unica di tolleranza abbastanza diversa dalla risposta immunitaria dei libri di testo. La ricerca, pubblicata su Cell , descrive come i macrofagi intestinali rispondono a un precedente insulto schermando i neuroni enterici , impedendo loro di morire quando i futuri agenti patogeni colpiscono. Questi risultati potrebbero in definitiva avere implicazioni cliniche per condizioni come la sindrome dell'intestino irritabile, che sono state collegate alla morte incontrollata dei neuroni intestinali.

"Stiamo descrivendo una sorta di memoria innata che persiste dopo che l'infezione primaria è scomparsa", afferma Daniel Mucida di Rockefeller. "Questa tolleranza non esiste per uccidere futuri agenti patogeni, ma per affrontare il danno che l'infezione provoca, preservando il numero di neuroni nell'intestino".

ENGLISH

A simple stomach bug could do a lot of damage. There are 100 million neurons scattered along the gastrointestinal tract—directly in the line of fire—that can be stamped out by gut infections, potentially leading to long-term GI disease.

But there may be an upside to enteric infection. A new study finds that mice infected with bacteria or parasites develop a unique form of tolerance quite unlike the textbook immune response. The research, published in Cell, describes how gut macrophages respond to prior insult by shielding enteric neurons, preventing them from dying off when future pathogens strike. These findings may ultimately have clinical implications for conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, which have been linked to the runaway death of intestinal neurons.

"We're describing a sort of innate memory that persists after the primary infection is gone," says Rockefeller's Daniel Mucida. "This tolerance does not exist to kill future pathogens, but to deal with the damage that infection causes—preserving the number of neurons in the intestine."

Neuronal cause of death

Known as the body's "second brain," the enteric nervous system is houses the largest depot of neurons and glia outside of the brain itself. The GI tract's own nervous system exists more or less autonomously, without significant input from the brain. It controls the movement of nutrients and waste by fiat, coordinating local fluid exchange and blood flow with authority not seen anywhere else in the peripheral nervous system.

If enough of those neurons die, the GI tract spirals out of control.

Mucida and colleagues reported last year that gut infections in mice can kill the rodents' enteric neurons, with disastrous consequences for gut motility. At the time, the researchers noted that the symptoms of IBS closely mirror what one might expect to see when enteric neurons die en masse—raising the possibility that otherwise minor gut infections might be decimating enteric neurons in some people more than others, leading to constipation and other unexplained GI conditions.

The researchers wondered whether the body has some mechanism of preventing neuronal loss following infection. In previous work, the lab had indeed demonstrated that macrophages in the gut produce specialized molecules that prevent neurons from dying in response to stress.

A hypothesis began to take shape. "We knew that enteric infections cause neuronal loss, and we knew that macrophages prevent neuronal cell death," Mucida says. "We wondered whether we were really looking at a single pathway. Does a prior infection activate these macrophages to protect the neurons in future infections?"

Bacteria versus parasites

Postdoctoral fellow Tomasz Ahrends and additional lab members first infected mice with a non-lethal strain of Salmonella, a standard bacterial source of food poisoning. The mice cleared the infection in about a week, losing a number of enteric neurons along the way. They then infected those same mice with another comparable foodborne bacterium. This time, the mice suffered no further loss of enteric neurons, suggesting that the first infection had created a tolerance mechanism that prevented neuronal loss.

The scientists found that common parasitic infections also have a similar impact. "In contrast to pathogenic bacteria, some parasites like helminths have learned to live within us without causing excessive harm to the tissue," he says. Indeed this family of parasites, which includes flukes, tapeworms, and nematodes, infect in a way that is more subtle than highly hostile bacteria. But they also induce even greater, and more far-reaching, protection.

During a primary bacterial infection, Mucida found, neurons call out to macrophages, which rush to the area and protect its vulnerable cells from future attacks. When a helminth insinuates itself into the gut, however, it is T cells that recruit the macrophages, sending them to even distant parts of the intestine to ensure that the whole gamut of enteric neurons are shielded from future harm.

At the end of the day, through different routes, bacterial and helminth infections were both leading to protection of enteric neurons.

Next, Ahrends repeated the experiments in mice from a pet store. "Animals in the wild have likely had some of these infections already," he says. "We would expect a pre-set tolerance to neuronal loss." Indeed, these animals suffered no neuronal loss from any infection. "They had a lot of helminths in general," Mucida says. "The parasitic infections were doing their jobs, preventing the neuronal losses that we have seen in isolated animals in the lab."

A gut feeling

Mucida is now hoping to determine the precise impact of neuronal loss in the GI tract. "We've observed that animals consume more calories without gaining more weight after neuronal loss," he says. "This may mean that the loss of enteric neurons is also impacting the absorption of nutrients, metabolic and caloric intake."

There may be more consequences of neuronal loss than we expected," he adds.

Mucida believes that this research could contribute to a more complete understanding of the underlying causes of IBS and related conditions. "One speculation is that the number of enteric neurons throughout your life is set by early childhood infections, which prevent you from losing neurons after every subsequent infection," Mucida explains.

People who for some reason do not develop tolerance may continue to lose enteric neurons throughout their life with every subsequent infection. Future studies will explore alternative methods of protecting enteric neurons, hopefully paving the way for therapies.

Da:

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2021-10-foodborne-diseases-gut-nervous.html

Commenti

Posta un commento