Genome editor CRISPR’s latest trick? Offering a sharper snapshot of activity inside the cell / L'ultimo trucco dell'editor del genoma di CRISPR? Offrire un'istantanea più nitida di attività all'interno della cellula.

Genome editor CRISPR’s latest trick? Offering a sharper snapshot of activity inside the cell / L'ultimo trucco dell'editor del genoma di CRISPR? Offrire un'istantanea più nitida di attività all'interno della cellula.

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

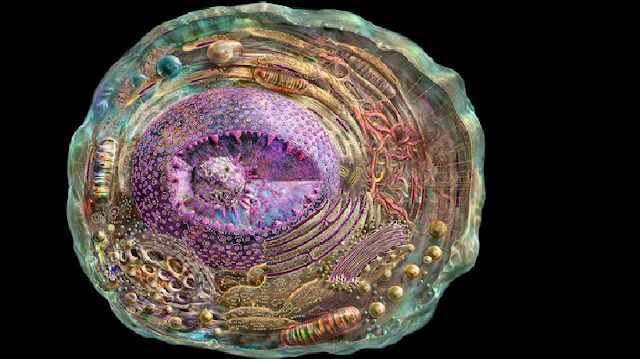

Cells are noisy places with lots of complex molecular conversations, and new strategies based on the genome editor CRISPR can record them. / Le cellule sono luoghi rumorosi con molte conversazioni molecolari complesse e nuove strategie basate sull'editor del genoma CRISPR possono registrarle.

Airplane flight recorders and body cameras help investigators make sense of complicated events. Biologists studying cells have tried to build their own data recorders, for example by linking the activity of a gene of interest to one making a fluorescent protein. Their goal is to clarify processes such as the emergence of cancer, aging, environmental impacts, and embryonic development. A new cellular recorder that borrows from CRISPR, the revolutionary genome editing tool, now offers what could be a better taping device that captures data on DNA.

In Science online this week, chemist David Liu and postdoc Weixin Tang, both of Harvard University, unveil two forms of what they call a CRISPR-mediated analog multievent recording apparatus, or CAMERA. In proof-of-concept experiments, they show in both bacterial and human cells how this tool can record exposure to light, antibiotics, and viral infection or document internal molecular events. "The study highlights the really creative ways people are harnessing discoveries in CRISPR to build these synthetic pathways," says Dave Savage, a protein engineer at the University of California, Berkeley.

Other investigators have created recording devices with CRISPR components, among them Timothy Lu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. But Lu notes that his system was limited to bacteria, and compared with CAMERA it required "an order of magnitude" more cells to reliably record signals and had a much poorer signal-to-noise ratio. The new work, he says, "is really beautiful stuff" and has "a level of efficiency and precision that goes beyond what we did earlier." (Lu this week plans to release a preprint describing a system similar to one version of CAMERA.)

The original use of CRISPR was to target and cut double-stranded DNA. Cells naturally repair these cuts, but in the process, they can introduce random, or stochastic, errors to a target gene, disabling it. Several groups have used these random errors as markers—or barcodes—to track how cells "differentiate" from one state to another.

Liu sought a cleaner readout. "We wanted to shy away from that stochastic mixture. It's much harder to interpret your findings." His team also aimed to record not just whether a cell experienced a stimulus, but how strong it was and how long it lasted. To better understand cancer, for example, Liu says, "We'd love to be able to see whether cells in certain states listen to or ignore signals to stop growing."

One form of CAMERA takes advantage of a peculiarity of bacteria: the circular "plasmids" of DNA that float in their cytoplasm, copying themselves but tightly regulating their population size. The researchers introduced two "recorder" plasmids, R1 and R2, that settle at a stable ratio. They then fashioned a separate plasmid with genes for CRISPR's components—a "guide" RNA (gRNA) that targets a DNA sequence and the Cas9 enzyme that cuts the double helix. Those genes are designed to kick into action, making the components that target R1 for destruction, when the cell experiences a specific stimulus. In one test, they equipped bacteria with an antibiotic-activated CAMERA. By sequencing the plasmids and documenting how the R1:R2 ratio had changed, they could tell how long the cells had been exposed to the drug.

A second CAMERA makes use of a modified Cas9 that doesn't cut the double helix and is linked to an enzyme that chemically switches cytosine, one of four DNA bases, into another one, thymine. To record an event, the gRNA shuttles this so-called base editor to a "safe harbor" gene, whose DNA can be altered without harming the cell. Again, the researchers tailor the system to respond to specific signals. As a test, they stimulated human cells to activate the Wnt signaling pathway, which plays a role in the development of embryos and in cancer. CAMERA turned on in the presence of Wnt activity, inscribing a record of those signals in the safe harbor gene.

CAMERA works in samples that contain as few as 10 cells, nearing the goal of recording the actions of a single cell. "If you're doing the activity map of the brain, each cell is a different story," notes Harvard geneticist George Church, whose own lab has developed CRISPR-based recording devices. "Ideally you'd have a nice single molecule ticker tape recording of a DNA sequence that you could read off and it tells you what was happening in each cell over the function of time."

CAMERA has other potentially useful features, including the ability to erase its recorded information, with drugs that "reset" the plasmid ratio to their baseline, for example. CAMERA also can record several different signals at the same time or one after the other. But for CAMERA to prove its worth in the crowded biological recording field, researchers have to show that it can work when engineered into the cells of an animal—not simply in the cell line used in Liu's Wnt experiment. "The real power is what's going to happen next," Savage says. "Right now, the killer app is still to come."

ITALIANO

I registratori di volo dell'aeroplano e le telecamere del corpo aiutano gli investigatori a dare un senso agli eventi complicati. I biologi che studiano le cellule hanno cercato di costruire i propri registratori di dati, ad esempio collegando l'attività di un gene di interesse a uno che produce una proteina fluorescente. Il loro obiettivo è quello di chiarire processi come l'emergere di cancro, invecchiamento, impatti ambientali e sviluppo embrionale. Un nuovo registratore cellulare che utiliza CRISPR, il rivoluzionario strumento di modifica del genoma, offre ora quello che potrebbe essere un dispositivo di registrazione migliore che cattura i dati sul DNA.

In Science online questa settimana, il chimico David Liu e il postdoc Weixin Tang, entrambi dell'Università di Harvard, svelano due forme di ciò che chiamano un apparecchio di registrazione multieventi analogico basato su CRISPR, o CAMERA. In esperimenti di proof-of-concept, mostrano in cellule sia batteriche che umane come questo strumento possa registrare esposizione alla luce, antibiotici e infezione virale o documentare eventi molecolari interni. "Lo studio mette in luce i modi davvero creativi con cui le persone stanno sfruttando le scoperte in CRISPR per costruire questi percorsi sintetici", dice Dave Savage, un ingegnere delle proteine presso l'Università della California, a Berkeley.

Altri investigatori hanno creato dispositivi di registrazione con componenti CRISPR, tra cui Timothy Lu del Massachusetts Institute of Technology di Cambridge. Ma Lu nota che il suo sistema era limitato ai batteri, e rispetto a CAMERA richiedeva "un ordine di grandezza" in più di cellule per registrare i segnali in modo affidabile e aveva un rapporto segnale / rumore molto più basso. Il nuovo lavoro, dice, "è davvero bello" e ha "un livello di efficienza e precisione che va al di là di quello che abbiamo fatto prima". (Lu questa settimana prevede di rilasciare una prestampa che descrive un sistema simile a una versione di CAMERA.)

L'uso originale di CRISPR era mirare e tagliare il DNA a doppio filamento. Le cellule riparano naturalmente questi tagli, ma nel processo, possono introdurre errori casuali o stocastici su un gene bersaglio, disabilitandolo. Diversi gruppi hanno usato questi errori casuali come indicatori o codici a barre per tenere traccia di come le cellule "si differenziano" da uno stato all'altro.

Liu ha cercato una lettura più pulita. "Volevamo evitare questa miscela stocastica, in quanto è molto più difficile interpretare le tue scoperte". Il suo gruppo ha anche mirato a registrare non solo se una cellula abbia subito uno stimolo, ma quanto è stata forte e quanto è durata. Per comprendere meglio il cancro, ad esempio, Liu afferma: "Ci piacerebbe essere in grado di vedere se le cellule in determinati stati ascoltano o ignorano i segnali per non crescere".

Una forma di CAMERA si avvale di una particolarità di batteri: i "plasmidi" circolari del DNA che galleggiano nel loro citoplasma, copiandosi ma regolando strettamente la loro dimensione di popolazione. I ricercatori hanno introdotto due plasmidi "registratori", R1 e R2, che si stabiliscono in un rapporto stabile. Hanno poi modellato un plasmide separato con geni per i componenti di CRISPR, un RNA "guida" (gRNA) che indirizza una sequenza di DNA e l'enzima Cas9 che taglia la doppia elica. Questi geni sono progettati per dare il via all'azione, attivando i componenti che hanno come target R1 la distruzione, quando la cellula sperimenta uno stimolo specifico. In un test, hanno equipaggiato i batteri con una CAMERA attivata dagli antibiotici. Sequenziando i plasmidi e documentando come il rapporto R1: R2 era cambiato, potevano dire per quanto tempo le cellule erano state esposte al farmaco.

Una seconda CAMERA fa uso di un Cas9 modificato che non taglia la doppia elica ed è collegato a un enzima che passa chimicamente la citosina, una delle quattro basi del DNA, in un'altra, la timina. Per registrare un evento, il gRNA sposta questo cosiddetto editor di base in un gene di "porto sicuro", il cui DNA può essere modificato senza danneggiare la cellula. Ancora una volta, i ricercatori adattano il sistema per rispondere a segnali specifici. Come test, hanno stimolato le cellule umane ad attivare la via di segnalazione Wnt, che svolge un ruolo nello sviluppo degli embrioni e nel cancro. CAMERA è stata attivata in presenza di attività Wnt, che registra un record di quei segnali nel gene del porto sicuro.

La CAMERA funziona in campioni che contengono solo 10 cellule, in prossimità dell'obiettivo da registrare le azioni di una singola cellula. "Se stai facendo la mappa dell'attività del cervello, ogni cellula è una storia diversa", osserva il genetista di Harvard George Church, il cui laboratorio ha sviluppato dispositivi di registrazione basati su CRISPR. "Idealmente avresti una bella registrazione a nastro di una singola molecola di una sequenza di DNA che potresti leggere e ti dirà cosa stava succedendo in ogni cellula per la durata di quel tempo."

Da:

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/02/genome-editor-crispr-s-latest-trick-offering-sharper-snapshot-activity-inside-cell?utm_campaign=news_daily_2018-02-15&et_rid=344224141&et_cid=1853355

Commenti

Posta un commento