‘I feel so much hope’—Is a new drug keeping this woman’s deadly Huntington disease at bay? / "Sento tanta speranza": è un nuovo farmaco che tiene a bada la mortale malattia di Huntington?

‘I feel so much hope’—Is a new drug keeping this

woman’s deadly Huntington disease at bay? / "Sento tanta

speranza": è un nuovo farmaco che tiene a bada la mortale malattia di

Huntington?

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa

/ Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

The dark shadow

of Huntington disease fell squarely over Michelle Dardengo’s life on the

day in 1986 that her 52-year-old father was found floating in the river in

Tahsis, the remote Vancouver Island mill town where she grew up. Richard Varney

had left his wedding ring, watch, and wallet on the bathroom counter; ridden

his bike to a bridge that spans the rocky river; and jumped. The 4.5-meter drop

broke his pelvis. The town doctor happened to be fishing below and pulled

Varney out as he floated downstream, saving his life.

But his tailspin

continued. The once funny man who read the Encyclopedia Britannica for

pleasure; the good dancer who loved ABBA, the Three Tenors, and AC/DC; the

affable volunteer firefighter—that man was disappearing. He was being replaced

by an erratic, raging misanthrope wedded to 40-ounce bottles of Bacardi whose

legs would not stay still when he reclined in his La-Z-Boy.

In 1988, Varney

was diagnosed with Huntington disease. That explained his transformation but

offered little comfort. Huntington is a brutal brain malady caused by a mutant

protein that inexorably robs victims of control of their movements and their

minds. Patients are plagued by jerky, purposeless movements called chorea. They

may become depressed, irritable, and impulsive. They inevitably suffer from

progressive dementia. The slow decline typically begins in midlife and lasts 15

to 20 years, as the toxic protein damages and finally kills neurons. For both

families and the afflicted, the descent is agonizing, not least because each

child of an affected person has a 50% chance of inheriting the fatal disease.

In the United

States, about 30,000 people have symptomatic Huntington disease and more than

200,000 carry the mutation that ensures they will develop it. Globally, between

three and 10 people in every 100,000 are affected, with those of European

extraction at highest risk. In a large study published in the Journal

of Neurology in June, Danish researchers found that people with

Huntington disease were nearly nine times more likely to attempt suicide than

the general population.

For the first 15

years after her father’s diagnosis, while scientists discovered the genetic

mutation that causes Huntington and embarked on a seemingly endless chase for a

remedy, Dardengo avoided the genetic testing that would reveal whether her

father’s decline was a preview of her future. Already married when her dad was

diagnosed, she gave birth to a son and a daughter and had a job she loved,

doing software diagnostics for an insurance company. Then in 2003, the year her

father died after being institutionalized for more than a decade, she got

tested. “It was bothering me,” she says. “You have to plan for the future.” She

was positive for the mutation.

About a decade

later, Dardengo noticed that her handwriting was becoming “unmanageable.” Her

balance declined. She returned from walking her dogs with bloody knees and

scraped hands. In April 2015—at 52, the same age that her father had leapt from

the bridge—she was forced to leave her job. “Cognitively, I don’t think you are

a good fit,” a new boss told her.

Then an

unfamiliar commodity entered her life: hope. Dardengo’s physician, Blair

Leavitt, a Huntington disease researcher at the University of British Columbia

(UBC) here, asked whether she wanted to join a nascent clinical trial of a new

medication made by a Carlsbad, California, biotechnology company, Ionis

Pharmaceuticals. The drug, the product of 25 years of research, was an

antisense molecule—a short stretch of synthetic DNA tailor-made to block

production of the Huntington protein.

Joining the

trial would be risky. Dozens of antisense drugs had entered clinical trials;

few had become approved drugs. This particular medicine, injected into the

fluid that surrounds the spinal cord, had never been put in humans. Dardengo

might receive the active drug or she might get a placebo. In August 2015, she

became “patient one."

Dardengo’s

father, shown holding her son Joel in a 1989 photo, died of Huntington disease.

Joel carries the mutation.

Three years

later, that trial is famous. Its results electrified the Huntington disease

community in December 2017 by indicating that the drug, formerly IONIS-HTTRx

and now called RG6042, reduces the amount of the culprit protein in the human

brain—the first time any medicine has done so. Preliminary data released in

April even hint at improvements in a few clinical measures.

The Basel,

Switzerland–based pharmaceutical company Roche, which licensed RG6042, is

preparing to move it into a pivotal clinical trial, with details to be

announced in the next few months. “We had emails and phone calls from patients

saying, ‘I want to join this [upcoming] trial now. I’m willing to move house to

do it,’” recalls Anne Rosser, a neuroscientist at Cardiff University, who

oversaw one of nine sites in the first trial.

She and others

who work with Huntington patients find themselves scrambling to manage

expectations. “One feels for these patients because the clock is ticking for

them,” Rosser says. But although the drug scored high for safety in the recent

trial, whether it slows or stops the disease simply isn’t known. “We haven’t

got evidence of efficacy,” she says. That will have to wait for the results of

the next trial. And some scientists still worry about the drug’s long-term

safety.

Given the

desperation of patients and their families, Louise Vetter, president and CEO of

the Huntington’s Disease Society of America in New York City, says her group

and others “need to manage back the hope a little bit. And that’s really hard.”

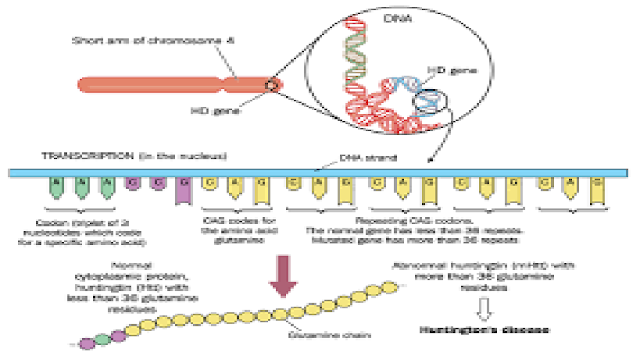

The mutation

that causes Huntington—named after U.S. physician George Huntington, who

described the disease in 1872—is located near the tip of the short arm of

chromosome 4. Healthy people carry two copies of the huntingtin gene, each with

up to 35 repetitions of a trio of nucleotides—cytosine, adenine, and guanine

(CAG). In the mutated gene, this CAG triplet is repeated 36 or more times, like

a stutter. People who inherit a copy of the mutant gene from one parent produce

a mutant huntingtin protein with an extra-long chain of glutamine amino acids.

No one is sure

just how the mutant protein damages neurons. But chains of glutamine longer

than 36 amino acids are much more likely to stick to each other, forming clumps

that may disrupt membranes or bind and inactivate other molecules within

neurons. Afflicted people produce mutant huntingtin throughout their lives, and

the damage mounts until symptoms appear. The more CAG repeats a patient

harbors, the sooner the inevitable day comes.

Regardless of

how the destruction happens, scientists reasoned, stopping production of the

mutant protein at its source should halt downstream damage. Back in 1992, Science declared

antisense technology one of the 10 hottest areas of the year; 1 year later, the

mutation that causes Huntington was published. Because just a single gene was

responsible, shutting it down with antisense seemed an obvious approach for a

therapy. The idea was that synthetic DNA snippets with a sequence complementary

to part of the huntingtin gene’s messenger RNA (mRNA) would bind to the mRNA.

In this case, the resulting DNA-mRNA complex summons a cutting enzyme, RNase H,

that degrades the mRNA and prevents its translation into protein.

But for 25 years

the idea wasn’t practical. Early antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) didn’t bind

mRNA targets efficiently and were quickly degraded by enzymes. Several

companies dropped out. By the early 2000s, having chemically improved the ASOs

and done animal studies, Ionis began to tailor ASOs to specific neurological

diseases, including one to curb spinal muscular atrophy.

In 2006, Ionis

researchers, led by the firm’s vice president of research, Frank Bennett,

launched a collaboration with neuroscientist Don Cleveland and postdoc Holly

Kordasiewicz of the University of California, San Diego, to develop an ASO to

attack Huntington disease. (Kordasiewicz has since joined Ionis.) By 2012, they

had a 20-letter ASO that reversed symptoms and slowed brain atrophy in mouse

models of Huntington. In macaques, dogs, and pigs, the researchers injected the

ASO into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which bathes the spinal cord and brain.

The drug reduced the mutant protein in key brain regions, including the cortex

and the corpus striatum, a deeper brain structure that is the disease’s first

target. And it appeared to be safe.

In early 2015,

researchers at several institutions delivered the last tool needed for a human

trial: new tests that could detect levels of mutant huntingtin protein in the

CSF. Crucially, one group also showed that in mice, reductions of mutant

protein in the CSF corresponded to reductions in the brain itself. Now,

researchers could collect human CSF and see reflected there how their ASO

likely affected levels of the toxic protein in patients’ brains.

In August 2015,

Dardengo lay on her side at UBC Hospital, her face to the wall. She felt

Leavitt’s needle inject anesthetic in the small of her back. After that, she

felt nothing while he withdrew 20 milliliters of her spinal fluid and replaced

it with the medication, dissolved in liquid. That was the first of four monthly

injections. The trial was double-blind: Neither she nor Leavitt knew whether

she was receiving placebo or the lowest of the planned doses of active drug,

the only dose given to the first subjects.

Dardengo was

unfazed by being patient one. “I never felt afraid,” she recalls. “Dr. Leavitt

always asked: ‘You know that you could die doing this?’ I always said: ‘Yes,

but my kids aren’t going to have to worry.’”

She thought she

felt better after the last monthly injection, but she saw no improvement in her

symptoms. Her balance was still off—she didn’t dare wear high heels—and she

still got stuck in the middle of sentences. Months earlier, she had quit

clipping her cat’s claws for fear of injuring the animal. Her husband Marc

Dardengo had stopped asking her to run errands for his business because she so

often got lost. These things didn’t change.

Then in November

2016, she and Marc received news that left them numb. Joel Dardengo, age 27,

told his parents he had been tested for the Huntington mutation. He was positive.

His mother’s

trial was cold comfort for Joel, a realist keenly aware of the pitfalls of

science. “You can YouTube the disease and see what the endgame looks like,” he

says. “It’s not the nicest.”

Joel told his

fiancée that she was free to leave him. She refused. The couple, who want to

have children, began to discuss in vitro fertilization, which would allow them

to implant only Huntington-free embryos. But Joel, an electronics technician,

and his fiancée, a prison guard, see no way to pay for the $30,000 procedure.

Thirteen months

later, at 12:01 a.m. on 11 December 2017, Michelle received an email: Ionis had

announced the results of the trial in a press release. (A paper is still in the

works.) After testing in 46 people, including her, RG6042 appeared to be safe,

with minimal side effects. And after four monthly doses, levels of mutant huntingtin in

patients’ CSF had decreased in a dose-dependent manner: The antisense molecule

appeared to be hitting its target.

The results

triggered a happy uproar among Huntington families. Michelle and Marc Dardengo

uncorked a bottle of chardonnay and toasted the possibility that their children

would live Huntington-free lives. Vetter, 5000 kilometers away, got a text

message from her scientific director telling her to check her email

immediately. She pulled over to the side of New Jersey’s Route 23, read the

Ionis press release, and wept. At Huntington disease clinics from Baltimore,

Maryland, to Bochum, Germany, phones began buzzing, email inboxes overflowing,

and appointment requests surging. At University College London, home to the

trial’s global leader, neurologist Sarah Tabrizi, patient referrals briefly

quadrupled.

On the same day

the results were revealed, Roche announced it had paid $45 million to license

the drug from Ionis and would move it into a pivotal clinical trial. That trial

will enroll hundreds of patients in Europe, Canada, and the United States for

up to 2 years, allowing the company to determine whether RG6042 slows or stops

the disease.

Ionis presented

more details about the first trial’s results at two meetings earlier this year.

In March, the company reported that levels of mutant protein in the two

highest-dose patient groups had declined on average by 40% and in some cases up

to 60%. (In lab animals, smaller reductions had reduced symptoms of the

disease.) And in April, Tabrizi reported that aggregated data from all patients

showed statistically significant improvement in three of five clinical measures

of Huntington disease progression, including tests of both motor and cognitive

function.

But researchers

were quick to temper the resulting excitement with caution. Bennett notes that

other clinical measures did not improve significantly. “You can always find

some correlations if you look hard enough. … The only way to really validate

this is to do additional longer-term studies.”

Tabrizi, who

like Leavitt consults for Roche and competing companies, agrees. She points out

that the first trial wasn’t designed to gauge effectiveness. “The big question

we have now is: Is the degree of mutant huntingtin lowering in

the brain enough to slow the disease’s progression?”

At the moment,

no one can say whether reduced protein levels will help already damaged brains

recover, how long any positive effects might last, or whether dangerous side

effects will crop up down the road. Tabrizi says patients should not expect

“some Lazarus-like effect.”

One scientist

not involved with the trial is even more circumspect. “People said in 1993: ‘We

have the gene—we have the cure,’” recalls Ole Isacson, a neurodegenerative

disease expert at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. In the mid-1990s, he ran a

first, failed experiment trying to suppress huntingtin production

in mice using an ASO. “And 25 years later, there may be a slight chance. This

is not a sure home run.

Although the

first trial appeared to show that RG6042 is safe, some researchers still have

concerns because the drug suppresses production of both the normal and mutant

forms of the huntingtin protein. Because mutant huntingtin genes

vary in sequence, a drug targeted to one version of the mutant allele would not

work for every patient. It also would be technically more challenging to

develop. So Ionis opted for a nonselective ASO that targets a sequence found in

all huntingtin genes, mutant and normal.

Doing so was a

calculated risk. No one knows whether normal huntingtin is

essential to brain health in adults. (It is essential to early development:

Mice without it perish as embryos.) Bennett notes that RG6042’s effects are

less drastic than deleting the gene entirely: “We’re not knocking out huntingtin [protein],

we’re reducing it.” Leavitt shares his confidence, noting that in Ionis’s

in-house work, “Nothing from the preclinical animal studies suggested any

toxicity.”

But 1 year ago,

scientists at The University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC) in

Memphis found something different, as they reported in PLOS Genetics.

They knocked out the huntingtin protein in mice at 3, 6, and 9

months of age. At all ages, the mice developed severe motor and behavioral

deficits and progressive brain pathology: The animals’ thalami—sensory and

motor signal relay stations—became calcified, and their brains atrophied.

“We end up

sounding like a Cassandra,” says Paula Dietrich, a neurobiologist at UTHSC who

was the paper’s first author. “We bring the bad news, and nobody wants to hear

or believe it.”

Dietrich

concedes that mice findings may not apply to humans. But she notes that huntingtin is

expressed throughout the brain and cautions that the levels of RG6042 needed to

penetrate the deeper structures where Huntington pathology begins could have

unwanted effects. “To reach efficacy in the striatum, you may have to expose

other regions of the brain to extremely high concentrations,” she says.

Another company,

Wave Life Sciences of Cambridge, Massachusetts, is developing two antisense

drugs aimed at suppressing only the mutant gene, leaving the normal one

untouched. Wave’s ASOs target two sequence variants, one or both of which occur

in 70% of Huntington patients. Both drugs are in initial clinical trials, with

results expected next summer, and the firm thinks its approach may be safer

than RG6042.

“No one knows

the longer-term implications of knocking down the healthy allele,” says Chandra

Vargeese, Wave’s senior vice president and head of research. “The expanded

allele is the causative factor. So why not leave the healthy allele intact?”

Michelle

Dardengo, on her way to a hiking trail with her dog, says her confidence behind

the wheel has improved since last year.

JOHN LEHMANN

By about 24

hours after injection into the CSF, RG6042 has diffused into neurons in the

brain, where it remains for 3 to 4 months. Bennett says animal studies tracing

the drug’s uptake and activity suggest that monthly injections of the highest

trial dose might begin to measurably improve symptoms after 6 months—if the

drug works.

In January,

Michelle Dardengo began to receive monthly injections of 120 milligrams of

RG6042—the highest dose dispensed in the first study. Along with 45 other

patients from that study, she is taking part in an open-label extension of the

trial. It is designed to produce long-term safety data and to chart all 46

patients’ disease progression. But for Dardengo, it is a trial of the drug’s

promise.

In an in-person

interview in March, shortly after her third such injection, Dardengo appeared

tired. Her speech was sometimes halting and stopped midsentence.

Three months

later, in a telephone interview in June, she spoke fluently, in complete

sentences. She was still gamely answering questions after 2 hours. “I find that

my speaking is a lot better. Like, I can actually finish a sentence,” she

volunteered.

Dardengo also

reports that she and her dogs are walking farther, on rougher trails, than was

her habit in January. She added: “My handwriting is becoming quite legible

now.” In July, Dardengo noted that she has resumed clipping the cat’s claws and

sent a video of herself doing so with apparently steady hands. Marc Dardengo

confirms that his wife’s walking stamina and hand-writing have improved, and he

notes that her violent leg movements while sleeping have virtually disappeared.

And he thinks that the deterioration of her memory has stabilized. “Before the

start of the [open label] trial, I could see her memory [go downhill] over the

course of a year. Since January, [with her] taking this drug, I am not seeing

that type of change.”

But he cautioned

that his wife’s verbal fluency is a moving target. “She has easier days with

conversation more often than before. But she also has days when the dots aren’t

connecting.”

And Joel

Dardengo believes his mother’s memory is getting worse. In June, for example,

she forgot to buy him a birthday cake, a long-standing tradition. Paying for a

pricey meal at a restaurant, she uncharacteristically failed to tip the server.

Trial scientists

Tabrizi and Leavitt strongly caution that one patient’s experience is an

anecdote, not a study. “An n of one is just that,” Leavitt

says, adding: “The placebo effect is very real. We don’t want to put out the

impression that [the drug] is working. Because we don’t know yet.” Tabrizi says

she and her team are doing their all—by phone, email, and in person—to

communicate that to patients.

Today, Michelle

Dardengo says her goal is to ride her bicycle in 6 months. To win Leavitt’s

permission to attempt this, she needs to pass the heel-to-toe walking test

administered to suspected drunk drivers without losing her balance, a feat that

eludes her today.

She is

nonetheless buoyant. “I feel so much hope,” she says. “Things are so different

between my dad and me: I’ve got a life to live.” For her son, her hopes are

even higher: “Joel could definitely be a candidate to potentially never see or

experience Huntington.”

Joel himself is

far more cautious. “I do wish for the best,” he says. “At the same time, I do

prepare for the worst.”

ITALIANO

L'Huntington è

una brutale malattia cerebrale causata da una proteina mutante che ruba

inesorabilmente le vittime del controllo dei loro movimenti e delle loro menti.

I pazienti sono afflitti da movimenti a scatti, senza scopo, chiamati corea.

Possono diventare depressi, irritabili e impulsivi. Soffrono inevitabilmente di

demenza progressiva. Il lento declino inizia tipicamente nella mezza età e dura

dai 15 ai 20 anni, poiché la proteina tossica danneggia e alla fine uccide i

neuroni. Per entrambe le famiglie e gli afflitti, la discesa è dolorosa, non

ultimo perché ogni bambino di una persona affetta ha il 50% di probabilità di

ereditare la malattia fatale.

Negli Stati

Uniti, circa 30.000 persone hanno una malattia sintomatica di Huntington e più

di 200.000 portano la mutazione che assicura che lo svilupperanno. A livello

globale, sono interessate da 3 a 10 persone ogni 100.000, con quelle di

estrazione europea a più alto rischio. In un ampio studio pubblicato nel

Journal of Neurology nel mese di giugno, i ricercatori danesi hanno scoperto

che le persone con la malattia di Huntington avevano quasi nove volte più

probabilità di tentare il suicidio rispetto alla popolazione generale.

Il medico di

Dardengo, Blair Leavitt, ricercatore della malattia di Huntington presso

l'Università della British Columbia (UBC), ha chiesto se voleva unirsi a una

nascente sperimentazione clinica di un nuovo farmaco realizzato da una società

di biotecnologia di Carlsbad, in California, Ionis Pharmaceuticals. Il farmaco,

frutto di 25 anni di ricerca, era una molecola antisenso, un breve tratto di

DNA sintetico fatto su misura per bloccare la produzione della proteina

Huntington.

Partecipare al

processo sarebbe rischioso. Dozzine di farmaci antisenso erano entrati in studi

clinici; pochi erano diventati farmaci approvati. Questa particolare medicina,

iniettata nel fluido che circonda il midollo spinale, non era mai stata messa

nell'uomo. Dardengo potrebbe ricevere il farmaco attivo o potrebbe ottenere un

placebo. Nell'agosto 2015 è diventata "paziente".

Tre anni dopo,

quel processo è famoso. I suoi risultati hanno elettrizzato la comunità della

malattia di Huntington nel dicembre 2017 indicando che il farmaco,

precedentemente IONIS-HTTRx e ora chiamato RG6042, riduce la quantità di

proteina colpevole nel cervello umano - la prima volta che una medicina lo ha

fatto. I dati preliminari pubblicati ad aprile suggeriscono anche miglioramenti

in alcune misure cliniche.

L'azienda

farmaceutica Roche, con sede a Basilea, Svizzera, che ha ottenuto la licenza

RG6042, si sta preparando a trasformarla in uno studio clinico fondamentale,

con dettagli da annunciare nei prossimi mesi. "Avevamo e-mail e telefonate

dei pazienti che dicevano: 'Voglio partecipare a questa [imminente] prova ora.

Sono disposto a trasferirmi casa per farlo ", ricorda Anne Rosser,

neuroscienziata dell'Università di Cardiff, che ha supervisionato uno dei nove

siti nel primo processo.

Lei e altri che

lavorano con i pazienti di Huntington si ritrovano a dover gestire le

aspettative. Ma sebbene il farmaco abbia ottenuto un punteggio elevato per la

sicurezza nel recente studio, non è noto se rallenta o arresti la malattia.

"Non abbiamo prove di efficacia", dice. Dovrà aspettare i risultati

del prossimo processo. E alcuni scienziati si preoccupano ancora della

sicurezza a lungo termine del farmaco.

Data la

disperazione dei pazienti e delle loro famiglie, Louise Vetter, presidente e

CEO della Huntington's Disease Society of America di New York City, afferma che

il suo gruppo e altri "hanno bisogno di riprendere un po 'la speranza. E

questo è davvero difficile. "

La mutazione che

provoca il nome di Huntington dopo che il medico statunitense George

Huntington, che descrisse la malattia nel 1872, si trova vicino alla punta del

braccio corto del cromosoma 4. Le persone sane portano due copie del gene

huntingtina, ciascuna con un massimo di 35 ripetizioni di un trio di

nucleotidi-citosina, adenina e guanina (CAG). Nel gene mutato, questa tripletta

CAG viene ripetuta 36 o più volte, come una balbuzie. Le persone che ereditano

una copia del gene mutante da un genitore producono una proteina huntingtina

mutante con una catena extra lunga di aminoacidi glutammina.

Nessuno è sicuro

di come la proteina mutante danneggia i neuroni. Ma le catene di glutammina più

lunghe di 36 amminoacidi hanno molte più probabilità di aderire l'una

all'altra, formando grumi che possono disturbare le membrane o legare e

inattivare altre molecole all'interno dei neuroni. Le persone afflitte

producono huntingtina mutante per tutta la vita, e il danno si innalza fino

alla comparsa dei sintomi. Più CAG si ripete, prima arriva l'inevitabile

giorno.

Indipendentemente

da come avviene la distruzione, gli scienziati hanno ragionato che, fermando la

produzione della proteina mutante alla sua origine si dovrebbe arrestare il

danno a valle. Nel 1992, Science dichiarò la tecnologia antisenso una delle 10

aree più calde dell'anno; 1 anno dopo è stata pubblicata la mutazione che causa

Huntington. Perché solo un singolo gene era responsabile, chiudendolo con

antisenso sembrava un approccio ovvio per una terapia. L'idea era che i

frammenti sintetici di DNA con una sequenza complementare a parte dell'RNA

messaggero del gene dell'huntingtina (mRNA) si legassero all'mRNA. In questo

caso, il risultante complesso DNA-mRNA evoca un enzima di taglio, RNasi H, che

degrada l'mRNA e ne impedisce la traduzione in proteine.

Ma per 25 anni

l'idea non era pratica. I primi oligonucleotidi antisenso (ASO) non legavano

gli obiettivi degli mRNA in modo efficiente e venivano rapidamente degradati

dagli enzimi. Diverse società si ritirarono. All'inizio degli anni 2000, dopo

aver migliorato chimicamente gli ASO e fatto studi sugli animali, Ionis iniziò

ad adattare gli ASO a specifiche malattie neurologiche, compresa quella per

frenare l'atrofia muscolare spinale.

Nel 2006, i

ricercatori di Ionis, guidati dal vicepresidente della ricerca dell'azienda,

Frank Bennett, hanno avviato una collaborazione con il neuroscienziato Don

Cleveland e il postdoc Holly Kordasiewicz dell'Università della California, a

San Diego, per sviluppare un ASO per attaccare la malattia di Huntington. (Da

allora Kordasiewicz è entrato a far parte di Ionis.) Nel 2012, avevano un ASO

di 20 lettere che invertiva i sintomi e rallentava l'atrofia cerebrale nei

modelli murini di Huntington. Nei macachi, nei cani e nei maiali, i ricercatori

hanno iniettato l'ASO nel liquido cerebrospinale (CSF), che bagna il midollo

spinale e il cervello. Il farmaco ha ridotto la proteina mutante in regioni

chiave del cervello, tra cui la corteccia e il corpo striato, una struttura

cerebrale più profonda che è il primo bersaglio della malattia. E sembrava

essere al sicuro.

All'inizio del

2015, i ricercatori di diverse istituzioni hanno consegnato l'ultimo strumento

necessario per un trial sull'uomo: nuovi test in grado di rilevare i livelli di

proteina huntingtina mutante nel liquido cerebrospinale. Fondamentalmente, un

gruppo ha anche dimostrato che nei topi, la riduzione della proteina mutante

nel liquido cerebrospinale corrispondeva a riduzioni nel cervello stesso. Ora,

i ricercatori potrebbero raccogliere il CSF umano e vedere riflesso come il

loro ASO probabilmente abbia influenzato i livelli della proteina tossica nel

cervello dei pazienti.

Nell'agosto

2015, Dardengo si trovava dalla sua parte all'ospedale UBC, con la faccia

contro il muro. Sentì l'ago di Leavitt iniettare anestetico nella sua piccola

schiena. Dopo di ciò, non sentì nulla mentre ritirava 20 millilitri del suo

fluido spinale e lo rimpiazzò con il farmaco, sciolto in un liquido. Quella fu

la prima di quattro iniezioni mensili. Il processo era in doppio cieco: né lei

né Leavitt sapevano se stava ricevendo il placebo o la più bassa delle dosi

programmate di farmaco attivo, l'unica dose somministrata ai primi soggetti.

Dardengo non si

preoccupava di essere paziente. "Non ho mai avuto paura", ricorda.

“Dr. Leavitt mi ha sempre chiesto: "Sai che potresti morire facendo

questo?" Ho sempre detto: "Sì, ma i miei figli non dovranno

preoccuparsi".

Pensò di

sentirsi meglio dopo l'ultima iniezione mensile, ma non vide alcun

miglioramento nei suoi sintomi. Il suo equilibrio era ancora spento - non osava

indossare i tacchi alti - e si bloccava ancora nel mezzo delle frasi. Mesi

prima, aveva smesso di tagliare gli artigli del suo gatto per paura di ferire

l'animale. Suo marito Marc Dardengo aveva smesso di chiederle di fare

commissioni per i suoi affari perché si perdeva così spesso. Queste cose non

sono cambiate.

Poi, a novembre

2016, lei e Marc hanno ricevuto notizie che li hanno lasciati insensibili. Joel

Dardengo, 27 anni, ha detto ai suoi genitori che era stato testato per la

mutazione di Huntington. Era positivo.

Il processo di

sua madre era un freddo conforto per Joel, un realista profondamente

consapevole delle insidie della scienza. "Puoi vedere su YouTube la

malattia e vedere com'è la partita finale", dice. "Non è il più

bello."

Joel ha detto

alla sua fidanzata che era libera di lasciarlo. Lei ha rifiutato. La coppia,

che desidera avere figli, ha iniziato a discutere della fecondazione in vitro,

che consentirebbe loro di impiantare solo embrioni esenti da Huntington. Ma

Joel, un tecnico dell'elettronica, e la sua fidanzata, una guardia carceraria,

non vedono alcun modo per pagare la procedura da $ 30.000.

Tredici mesi

dopo, alle 12:01 dell'11 dicembre 2017, Michelle ha ricevuto un'e-mail: Ionis

aveva annunciato i risultati del processo in un comunicato stampa. (Un articolo

è ancora in lavorazione.) Dopo aver testato 46 persone, inclusa lei, RG6042

sembrava essere sicuro, con effetti collaterali minimi. E dopo quattro dosi

mensili, i livelli di huntingtina mutata nel CSF dei pazienti erano diminuiti

in modo dose-dipendente: la molecola antisenso sembrava colpire il bersaglio.

I risultati

hanno scatenato un tumulto felice tra le famiglie di Huntington. Michelle e

Marc Dardengo stapparono una bottiglia di chardonnay e brindarono alla

possibilità che i loro figli vivessero una vita libera da Huntington. Vetter, a

5000 chilometri di distanza, ha ricevuto un messaggio dal suo direttore

scientifico che le diceva di controllare immediatamente la sua email. Si

avvicinò al lato della Route 23 del New Jersey, lesse il comunicato stampa di

Ionis e pianse. Alle cliniche della malattia di Huntington da Baltimora, nel

Maryland, a Bochum, in Germania, i telefoni hanno iniziato a ronzare, le e-mail

in arrivo traboccavano e le richieste di appuntamento aumentavano.

All'University College di Londra, sede del leader globale del processo, la

neurologa Sarah Tabrizi, i pazienti si sono brevemente quadruplicati.

Lo stesso giorno

in cui i risultati sono stati rivelati, Roche ha annunciato di aver pagato $ 45

milioni per acquistare il farmaco da Ionis e lo avrebbe trasformato in uno

studio clinico cruciale. Questo studio registrerà centinaia di pazienti in

Europa, Canada e Stati Uniti per un massimo di 2 anni, consentendo alla società

di determinare se RG6042 rallenta o arresta la malattia.

Ionis ha

presentato maggiori dettagli sui primi risultati del trial in due incontri

all'inizio di quest'anno. A marzo, la società ha riferito che i livelli di

proteina mutante nei due gruppi di pazienti con dosi più elevate erano

diminuiti in media del 40% e in alcuni casi fino al 60%. (In animali da

laboratorio, riduzioni più ridotte hanno ridotto i sintomi della malattia). In

aprile, Tabrizi ha riferito che i dati aggregati di tutti i pazienti hanno

mostrato un miglioramento statisticamente significativo in tre delle cinque

misure cliniche della progressione della malattia di Huntington, compresi test

della funzione motoria e cognitiva .

Ma i ricercatori

sono stati rapidi a moderare l'eccitazione risultante con cautela. Bennett

osserva che altre misure cliniche non sono migliorate in modo significativo.

"È sempre possibile trovare alcune correlazioni se si guarda abbastanza

bene. ... L'unico modo per validare veramente questo è fare ulteriori studi a

lungo termine. "

Tabrizi, che

come Leavitt consulta per Roche e le società concorrenti, è d'accordo.

Sottolinea che la prima prova non è stata progettata per valutare l'efficacia.

"La grande domanda che abbiamo ora è: il livello di huntingtina mutata sta

diminuendo nel cervello abbastanza da rallentare la progressione della

malattia?"

Al momento,

nessuno può dire se i livelli proteici ridotti aiuteranno a recuperare i

cervelli già danneggiati, quanto a lungo potrebbero durare gli effetti positivi

o se gli effetti collaterali pericolosi si ripercuoteranno lungo la strada.

Tabrizi dice che i pazienti non dovrebbero aspettarsi "qualche effetto

simile a Lazzaro".

Uno scienziato

non coinvolto nel processo è ancora più cauto. "La gente diceva nel 1993:

'Abbiamo il gene - abbiamo la cura'", ricorda Ole Isacson, un esperto di

malattie neurodegenerative presso l'Harvard Stem Cell Institute. A metà degli

anni '90, ha condotto un primo esperimento fallito cercando di sopprimere la

produzione di huntingtina nei topi usando un ASO. "E 25 anni dopo, ci può

essere una leggera possibilità. Questa non è una corsa sicura.

Sebbene il primo

studio abbia dimostrato che RG6042 è sicuro, alcuni ricercatori hanno ancora

preoccupazioni perché il farmaco sopprime la produzione di entrambe le forme

normali e mutanti della proteina huntingtina. Poiché i geni mutanti

dell'huntingtina variano in sequenza, un farmaco indirizzato a una versione

dell'allele mutante non funzionerebbe per tutti i pazienti. Sarebbe anche

tecnicamente più difficile da sviluppare. Così Ionis ha optato per un ASO non

selettivo che si rivolge a una sequenza trovata in tutti i geni huntingtina,

mutante e normale.

Fare così era un

rischio calcolato. Nessuno sa se l'huntingtina normale sia essenziale per la

salute del cervello negli adulti. (È essenziale per il primo sviluppo: i topi

senza perire come embrioni). Bennett nota che gli effetti dell'RG6042 sono meno

drastici dell'eliminazione completa del gene: "Non stiamo eliminando la

huntingtina [proteina], la stiamo riducendo." Leavitt condivide la sua

fiducia, osservando che nel lavoro interno di Ionis, "Nulla degli studi

preclinici sugli animali ha suggerito alcuna tossicità".

Ma un anno fa,

gli scienziati dell'University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC) di

Memphis trovarono qualcosa di diverso, come riportato in PLOS Genetics. Hanno

eliminato la proteina huntingtina nei topi a 3, 6 e 9 mesi di età. A tutte le

età, i topi svilupparono gravi deficit motori e comportamentali e una

progressiva patologia cerebrale: le stazioni di ritrasmissione dei segnali dei

thalami-sensoriali e dei segnali motorio degli animali - divennero calcificati

e il loro cervello si atrofizzò.

"Finiremo

per sembrare una Cassandra", dice Paula Dietrich, neurobiologa dell'UTHSC,

che fu il primo autore del giornale. "Portiamo le cattive notizie, e

nessuno vuole sentirlo o crederci."

Dietrich ammette

che i risultati sui topi potrebbero non essere applicabili agli esseri umani.

Ma nota che l'huntingtina è espressa in tutto il cervello e avverte che i

livelli di RG6042 necessari per penetrare nelle strutture più profonde dove

inizia la patologia di Huntington potrebbero avere effetti indesiderati.

"Per raggiungere l'efficacia nello striato, potresti dover esporre altre

regioni del cervello a concentrazioni estremamente elevate", dice.

Un'altra

società, la Wave Life Sciences di Cambridge, nel Massachusetts, sta sviluppando

due farmaci antisenso volti a sopprimere solo il gene mutante, lasciando

intatto quello normale. Gli ASO di Wave hanno come bersaglio due varianti di

sequenza, una o entrambe le quali si verificano nel 70% dei pazienti di

Huntington. Entrambi i farmaci sono in fase iniziale di sperimentazione

clinica, con risultati attesi per la prossima estate e l'azienda ritiene che il

suo approccio potrebbe essere più sicuro di RG6042.

"Nessuno

conosce le implicazioni a lungo termine di abbattere l'allele sano",

afferma Chandra Vargeese, vice presidente senior di Wave e responsabile della

ricerca. "L'allele espanso è il fattore causale. Quindi perché non

lasciare intatto l'allele sano? "

Michelle

Dardengo, sulla strada per un sentiero con il suo cane, dice che la sua fiducia

al volante è migliorata dallo scorso anno.

JOHN LEHMANN

Circa 24 ore

dopo l'iniezione nel liquido cerebrospinale, l'RG6042 si è diffuso nei neuroni

del cervello, dove rimane per 3 o 4 mesi. Bennett afferma che gli studi sugli

animali per tracciare l'assorbimento del farmaco e l'attività suggeriscono che

iniezioni mensili della più alta dose di prova potrebbero iniziare a migliorare

in modo misurabile i sintomi dopo 6 mesi, se il farmaco funziona.

A gennaio,

Michelle Dardengo ha iniziato a ricevere iniezioni mensili di 120 milligrammi

di RG6042, la dose massima erogata nel primo studio. Insieme ad altri 45

pazienti dello studio, sta prendendo parte a un'estensione in aperto della

sperimentazione. È progettato per produrre dati di sicurezza a lungo termine e

per tracciare la progressione della malattia di tutti i 46 pazienti. Ma per

Dardengo, è una prova della promessa della droga.

In un'intervista

di persona a marzo, poco dopo la sua terza iniezione, Dardengo sembrava stanco.

Il suo discorso a volte si fermava e si fermava a metà frase.

Tre mesi dopo,

in un'intervista telefonica a giugno, parlava fluentemente, in frasi complete.

Stava ancora rispondendo alle domande dopo 2 ore. "Trovo che il mio

parlare sia molto meglio. Come, posso davvero finire una frase, "si offrì

volontaria.

Dardengo

riferisce anche che lei ei suoi cani stanno camminando più lontano, su sentieri

più grezzi, di quanto non fosse sua abitudine a gennaio. Ha aggiunto: "La

mia calligrafia sta diventando piuttosto leggibile adesso." A luglio,

Dardengo ha notato che ha ripreso a tagliare gli artigli del gatto e ha inviato

un video di se stessa facendo così con le mani apparentemente ferme. Marc

Dardengo conferma che la resistenza alla deambulazione di sua moglie e la

scrittura a mano sono migliorate, e osserva che i suoi violenti movimenti delle

gambe durante il sonno sono praticamente scomparsi. E pensa che il

deterioramento della sua memoria si sia stabilizzato. "Prima dell'inizio

della prova [open label], ho potuto vedere la sua memoria [andare in discesa]

nel corso di un anno. Da gennaio, [con lei] che prende questo farmaco, non vedo

quel tipo di cambiamento ".

Ma ha avvertito

che la fluidità verbale della moglie è un bersaglio mobile. "Ha giorni più

facili con la conversazione più spesso di prima. Ma ha anche giorni in cui i

punti non si connettono. "

E Joel Dardengo

crede che la memoria di sua madre stia peggiorando. A giugno, ad esempio, ha

dimenticato di comprargli una torta di compleanno, una tradizione di lunga

data. Pagare un pasto costoso in un ristorante, lei insolitamente non è

riuscita a dare la mancia al server.

Gli scienziati

di prova Tabrizi e Leavitt avvertono con forza che l'esperienza di un paziente

è un aneddoto, non uno studio. "An one of one è proprio questo", dice

Leavitt, aggiungendo: "L'effetto placebo è molto reale. Non vogliamo dare

l'impressione che [il farmaco] stia funzionando. Perché non lo sappiamo ancora.

"Tabrizi dice che lei e il suo gruppo stanno facendo tutto per telefono,

e-mail e di persona per comunicarlo ai pazienti.

Oggi, Michelle

Dardengo dice che il suo obiettivo è di andare in bicicletta in 6 mesi. Per

ottenere il permesso di Leavitt di tentare ciò, ha bisogno di passare il test

del tallone ai piedi somministrato a sospetti guidatori ubriachi senza perdere

l'equilibrio, un'impresa che oggi le sfugge.

Nondimeno è

vivace. "Sento tanta speranza", dice. "Le cose sono così diverse

tra me e mio padre: ho una vita da vivere". Per suo figlio, le sue

speranze sono ancora più alte: "Joel potrebbe essere sicuramente un

candidato per non vedere o sperimentare potenzialmente Huntington."

Joel stesso è

molto più cauto. "Desidero il meglio", dice. "Allo stesso tempo,

mi preparo per il peggio."

Da:

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/08/i-feel-so-much-hope-new-drug-keeping-woman-s-deadly-huntington-disease-bay?utm_campaign=news_daily_2018-08-21&et_rid=344224141&et_cid=2301403

Commenti

Posta un commento