Hiv: i test, le terapie e le sfide della ricerca trent’anni dopo / HIV: tests, therapies and research challenges thirty years later

Hiv: i test, le terapie e le sfide della ricerca trent’anni dopo / HIV: tests, therapies and research challenges thirty years later

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

Conosciamo l’Hiv da più di tre decenni. Da quando, agli inizi degli anni Ottanta, cominciarono a diffondersi le prime notizie circa insolite infezioni e casi di rari tumori, collegati a un cattivo funzionamento del sistema immunitario, tra la comunità gay negli Usa. Ragion per cui la malattia, ancora misteriosa, si guadagnò l’appellativo di “cancro dei gay”, e “immuno-deficenza collegata ai gay”. Anche se ben presto fu chiaro, almeno alla comunità scientifica, che l’epidemia non colpiva solo gli omosessuali, e non era circoscritta dai confini Usa ma era un problema di portata mondiale.

La patologia fu associata a un’infezione virale solo a partire dal 1983, quando fu identificato il virus Hiv (Human Immunodeficiency Virus). Poi si accertò che la trasmissione poteva avvenire per via sessuale ma anche per contatto con sangue infetto, con lo scambio di siringhe e da madre a figlio.

Alla metà degli anni Ottanta l’impennata di casi di Aids e la mortalità elevatissima, anche nel giro di mesi anni dalla diagnosi, suscitò un’ondata di paura. Poi negli anni, l’Hiv è via via diventato meno inquietante. Grazie alle terapie che, arrivate dopo anni di tentativi, hanno rivoluzionato le cure, e anche la prevenzione della malattia. Tanto che oggi le persone sieropositive possono avere aspettative di vita paragonabili a quelle delle persone non infette. Oggi quasi 37 milioni di persone nel mondo convivono con il virus.

Il virus dell’Hiv e il sistema immunitario

Una volta infettati con il virus dell’Hiv l’infezione rimane a vita. Questo perché, ricordano i Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Cdc), il nostro corpo non è in grado di liberarsi dal virus, anche se sotto trattamento.

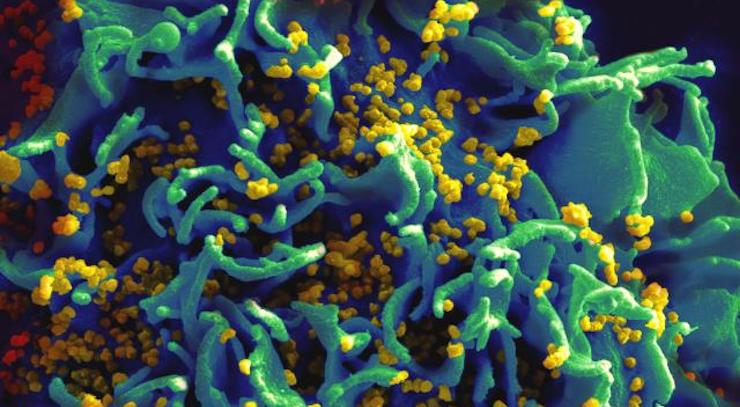

L’Hiv colpisce alcune cellule del sistema immunitario, un sottogruppo di linfociti T noti come CD4, che aiutano a combattere le infezioni. Il virus ne sovverte il funzionamento, utilizzandole come macchinario per replicarsi, e, se non trattato, nel tempo compromette a tal punto il funzionamento del sistema immunitario da renderlo incapace di combattere contro le infezioni ma anche da alcuni tipi di tumore. Tanto che le persone con Hiv hanno un più alto rischio di alcuni tumori. Se non contrastato, il virus prospera praticamente indisturbato, fino a sviluppare l’AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome).

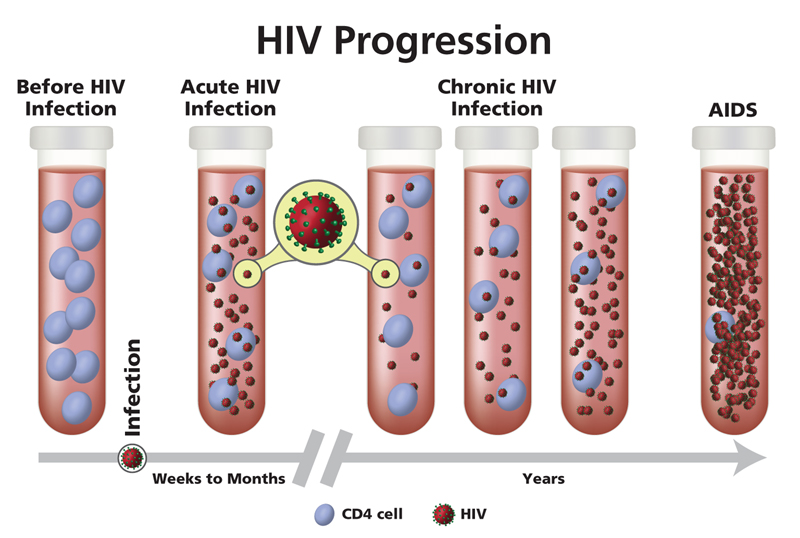

La sindrome da immunodeficienza acquisita è considerata come l’ultimo stadio dell’infezione da Hiv, quello il cui il sistema di difesa del corpo è così danneggiato che compaiono una serie di malattie opportunistiche. La presenza di infezioni opportunistiche o di livelli critici, sotto una determinata soglia, di cellule CD4 porta alla diagnosi di AIDS. I farmaci disponibili contro l’Hiv, di contro, impedendo la moltiplicazione del virus, possono arrestare la corsa verso la distruzione delle cellule CD4. In questo modo l’infezione cronica può rimanere asintomatica per anni.

I test per l’Hiv

Per beneficiare delle terapie oggi disponibili, ovviamente è necessario accertare l’avvenuta infezione il prima possibile, cosa che è possibile eseguendo un test, anche fai da te, a casa, acquistando il kit in farmacia.

I test oggi disponibili possono rivelare la presenza del genoma virale, del virus e degli anticorpi prodotti contro l’Hiv (come accade per quelli fai da te). Alcuni possono rivelare l’Hiv più precocemente rispetto al momento dell’esposizione al virus, come quelli che misurano la presenza di genomi e antigeni virali: gli anticorpi contro l’Hiv impiegano infatti un po’ di tempo a formarsi, da tre settimane a tre mesi. Nessun test però può evidenziare la presenza del virus subito dopo l’infezione.

I test oggi disponibili possono rivelare la presenza del genoma virale, del virus e degli anticorpi prodotti contro l’Hiv (come accade per quelli fai da te). Alcuni possono rivelare l’Hiv più precocemente rispetto al momento dell’esposizione al virus, come quelli che misurano la presenza di genomi e antigeni virali: gli anticorpi contro l’Hiv impiegano infatti un po’ di tempo a formarsi, da tre settimane a tre mesi. Nessun test però può evidenziare la presenza del virus subito dopo l’infezione.

Come funzionano le terapie

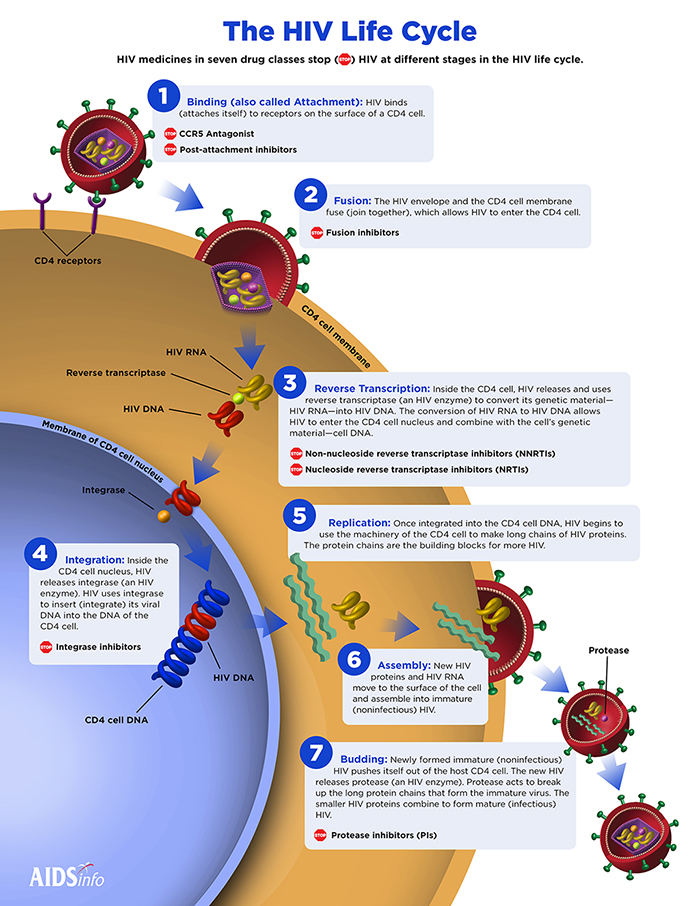

Dalla metà degli anni Novanta la storia dell’Hiv è stata rivoluzionata. Il cambio di paradigma è arrivato con le prime terapie antiretrovirali: farmaci in grado di bloccare la replicazione del virus. Agendo a diversi livelli del ciclo vitale del virus, questi medicinali di fatto impediscono la distruzione dei linfociti T CD4 da parte dell’Hiv. E più CD4 vitali una maggiore difesacontro agenti infettivi e un rallentamento degli effetti della malattia.

Esistono diverse tipologie di farmaci, che bloccano il virus a vari stadi: il regime terapeutico per ogni paziente comprende più medicinali, che agiscono con meccanismi diversi (i regimi di trattamento iniziale comprendono in genere tre farmaci combinati, di almeno due classi diverse).

La somministrazione delle terapie è giornaliera, ma ci sono tentativi, alcuni molto promettenti, che mirano a ridurre l’assunzione a una sola volta al mese, tramite iniezioni. I trattamenti antiretrovirali hanno così rivoluzionato la storia dell’Hiv che oggi, la ricerca su nuove terapie – compresi vaccini preventivi e tecniche di editing genetico sulle cellule del pazienti per renderli immuni al virus – vanno considerate soprattutto come strategie accessorie alle terapie antiretrovirali, pilastro della lotta al virus.

Perché è difficile eliminare l’Hiv

Le terapie antiretrovirali (ART) arrivate negli anni Novanta hanno stravolto la gestione della malattia ma non l’hanno eliminata. Questo perché bloccano la replicazione virale ma non riescono ad agire sul virus latente. L’Hiv infatti, dopo aver infettato le cellule, non sempre inizia a sfruttarle per replicarsi ma può rimanere al loro interno in uno stadio dormiente, latente. C’è ma non è attivo, e non si vede. Queste cellule immunitarie infettate dal virus ma che non producono altre particelle virali sono dette reservoir o serbatoi virali, e sono uno degli scogli più duri nella lotta al virus, perché sfuggono ai farmaci, alle armi che abbiamo oggi a disposizione per combattere l’Hiv.

I reservoir del virus possono trovarsi nei linfonodi, nel sangue, nel cervello, nel tratto digestivo. Possono rimanere latenti per anni, ma possono anche risvegliarsi. Ecco perché anche quando i livelli del virus sono ridotti è necessario continuare a seguire le terapieanche in quei casi in cui il virus non è stato più rintracciabile per diverso tempo.

Buona parte della ricerca contro l’Hiv oggi mira a risolvere proprio il problema dei serbatoi virali. Le strategie tentate sono diverse: alcune mirano a risvegliare il virus, così da renderlo un bersaglio sensibile e soprattutto visibile per il sistema immunitario o per i farmaci, altre, con tecniche di terapia genica, mirano ad eliminare il genoma virale da questi serbatoi. L’impresa però è ardua perché il virus può mutare nel tempo e diventare resistente ai trattamenti disponibili, che diventano così inefficaci.

Quando il virus diventa resistente riacquisisce la capacità di moltiplicarsi, anche sotto trattamento. È per questo che oggi il monitoraggio di virus resistenti e la ricerca di nuove soluzioni che siano efficaci contro queste forme rappresentano una delle principali sfide nella lotta al virus e alla sua eradicazione.

La terapia antiretrovirale è prevenzione

Aderire alla terapia è fondamentale. Un paziente ben trattato, e trattato precocemente, riesce a controllare la moltiplicazione del virus, e può mirare ad avere un’aspettativa di vitaparagonabile a quella dei sieronegativi, tanto che oggi la sfida per chi ha già contratto l’infezione è quella dell’invecchiamento.

Mantenere l’aderenza alla terapia è fondamentale per ridurre le resistenze ai farmaci, ma soprattutto perché i trattamenti antiretrovirali possono abbassare sensibilmente la quantità di virus in circolo, al punto tale da ridurre sensibilmente il rischio di trasmettere il virus. È per questo che ormai da qualche anno le terapie antitrovirali sono considerate una forma diprevenzione: il trattamento rende l’infezione meno contagiosa. Ma il concetto di prevenzione legato all’assunzione delle terapie è ben più ampio.

Assumere le terapie consente di scongiurare sensibilmente il rischio di trasmissionedell’infezione da madre a figlio e i trattamenti possono avere una funzione anche profilattica: l’assunzione delle terapie antiretrovirali diminuisce il pericolo di contrarre il virus in persone sieronegative. Un concetto quest’ultimo cui ci si riferisce con l’acronimo PreP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis), che potrebbe rappresentare un’arma in più nella lotta all’Hiv, per esempio nel caso di persone ad alto rischio di infezione, come le coppie sierodiscordanti, in cui uno dei partner ha l’infezione virale. La terapia ART è raccomandata per tutte le persone sieropositive con regimi diversi a seconda delle caratteristiche cliniche e della possibile interazione con altri farmaci.

Hiv, cosa ci resta da fare

In trent’anni l’epidemia di Hiv conta 77 milioni di persone infettate e più di 35 milioni di morti AIDS correlate. Al momento, ogni anno si registrano 1,8 milioni di nuove infezioni e 940 mila morti collegate all’AIDS (dati riferiti al 2017).

Sono numeri che raccontano quanto ancora rimane da fare nella lotta al virus, continuando a investire nello sviluppo e nell’accesso alle terapie, ma anche in prevenzione e ricerca. La prevenzione continua a essere un pilastro fondamentale nell’arginare le nuove infezioni, contro cui è necessario mettere in campo tutte le armi che abbiamo a disposizione: dai test per conoscere il proprio stato, all’uso dei preservativi, all’accesso ai trattamenti, anche in chiave di profilassi farmacologica. Ma è opinione diffusa che per mettere fine all’epidemia serve un vaccino (preventivo, ovvero in grado di scongiurare il rischio di infezione in persone sane, e non terapeutico come strategia di trattamento per le persone che sono già infette). Soprattutto negli hotspot dell’infezione, dove le probabilità di diffusione sono più elevate: in una prevalenza globale dell’infezione tra gli adulti dello 0,8%, la regione dell’Africa subsahariana raggiunge picchi di 4,2%.

ENGLISH

HIV-positive people may have life expectancies comparable to those of non-infected people. But the disease is not yet defeated: to eradicate HIV, we need to learn how to "flush" the virus out of its hiding places. And a vaccine

We've known HIV for over three decades. Since the first news began to spread in the early 1980s about unusual infections and cases of rare tumors, linked to a malfunctioning immune system, among the gay community in the US. This is why the disease, still mysterious, earned the title of "gay cancer", and "immuno-deficiency connected to gays". Although it was soon clear, at least to the scientific community, that the epidemic did not only affect homosexuals, and was not confined by the US borders but was a worldwide problem.

The disease was associated with a viral infection only from 1983 when the HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) virus was identified. Then it was ascertained that the transmission could take place through sexual contact but also through contact with infected blood, with the exchange of syringes and from mother to child.

In the mid-1980s the surge in AIDS cases and very high mortality, even within months of diagnosis, caused a wave of fear. Then over the years, HIV has gradually become less disturbing. Thanks to the therapies that, after years of attempts, have revolutionized treatment, and also the prevention of disease. So much so that today HIV-positive people can have life expectancies comparable to those of non-infected people. Today, almost 37 million people in the world live with the virus.

The HIV virus and the immune system

Once infected with the HIV virus the infection remains for life. This is because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recall, our body is not able to get rid of the virus, even if under treatment.

HIV affects some cells of the immune system, a subset of T lymphocytes known as CD4, which help fight infections. The virus subverts its functioning, using them as machinery for replication, and, if untreated, over time compromises the functioning of the immune system to such an extent that it becomes incapable of fighting infections but also of certain types of cancer. So much so that people with HIV have a higher risk of some cancers. If not contrasted, the virus thrives practically undisturbed, to the point of developing AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome).

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is considered to be the last stage of HIV infection, one in which the body's defense system is so damaged that a series of opportunistic diseases appear. The presence of opportunistic infections or critical levels, below a certain threshold, of CD4 cells leads to the diagnosis of AIDS. The drugs available against HIV, by contrast, by preventing the multiplication of the virus, can stop the race towards the destruction of CD4 cells. In this way, a chronic infection can remain asymptomatic for years.

HIV tests

To benefit from the therapies available today, it is obviously necessary to ascertain the infection occurred as soon as possible, which is possible by performing a test, even DIY, at home, buying the kit at the pharmacy.

The tests available today can reveal the presence of the viral genome, of the virus and antibodies produced against HIV (as happens for those do it yourself). Some may reveal HIV earlier than when exposed to the virus, such as those that measure the presence of viral genomes and antigens: HIV antibodies take some time to form, from three weeks to three months. However, no test can show the presence of the virus immediately after infection.

How therapies work

Since the mid-nineties, the history of HIV has been revolutionized. The paradigm shift came with the first antiretroviral therapies: drugs capable of blocking the replication of the virus. By acting at different levels of the life cycle of the virus, these drugs effectively prevent the destruction of CD4 T lymphocytes by HIV. And more viable CD4 a greater defense against infectious agents and a slowing of the effects of the disease.

There are different types of drugs, which block the virus at various stages: the therapeutic regimen for each patient includes more medicines, which act with different mechanisms (the initial treatment regimens generally include three combined drugs, of at least two different classes).

The administration of the therapies is daily, but there are attempts, some very promising, that aim to reduce the intake to only once a month, through injections. The antiretroviral treatments have thus revolutionized the history of HIV that today, the research on new therapies - including preventive vaccines and genetic editing techniques on patients' cells to make them immune to the virus - must be considered above all as accessory strategies to antiretroviral therapies, pillar of fight against the virus.

Why it is difficult to eliminate HIV

The antiretroviral therapies (ART) arrived in the nineties have upset the management of the disease but have not eliminated it. This is because they block viral replication but fail to act on the latent virus. In fact HIV, after having infected the cells, does not always start to exploit them to replicate itself but it can remain inside them in a dormant, dormant stage. There is but it is not active, and it is not visible. These immune cells infected by the virus but which do not produce other viral particles are called reservoirs or viral reservoirs, and are one of the hardest reefs in the fight against the virus, because they escape drugs, the weapons we have today to fight HIV.

The virus's reservoirs can be found in the lymph nodes, in the blood, in the brain, in the digestive tract. They can remain dormant for years, but they can also awaken. That is why even when the virus levels are reduced it is necessary to continue to follow the therapies even in those cases in which the virus has not been detectable for some time.

Much of the research against HIV today aims to solve the problem of viral reservoirs. The attempted strategies are different: some aim to awaken the virus, so as to make it a sensitive target and above all visible for the immune system or for drugs, others, with gene therapy techniques, aim to eliminate the viral genome from these reservoirs. However, the company is difficult because the virus can change over time and become resistant to available treatments, which become ineffective.

When the virus becomes resistant it regains the ability to multiply, even under treatment. This is why today the monitoring of resistant viruses and the search for new solutions that are effective against these forms represent one of the main challenges in the fight against the virus and its eradication.

Antiretroviral therapy is prevention

Joining therapy is essential. A patient who is well treated, and treated early, manages to control the multiplication of the virus and can aim to have a life expectancy comparable to that of seronegative, so much so that today the challenge for those who have already contracted the infection is aging.

Maintaining adherence to therapy is essential to reduce drug resistance, but above all because antiretroviral treatments can significantly reduce the amount of circulating virus, to the point of significantly reducing the risk of transmitting the virus. This is why for some years now antiretroviral therapies have been considered a form of prevention: the treatment makes the infection less contagious. But the concept of prevention linked to the assumption of therapies is much broader.

Taking the therapies allows you to significantly avoid the risk of transmission from mother to child and treatments can also have a prophylactic function: taking antiretroviral therapies decreases the risk of contracting the virus in seronegative people. A latter concept referred to by the acronym PreP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis), which could represent an additional weapon in the fight against HIV, for example in the case of people at high risk of infection, such as couples serodiscordant, in which one of the partners has the viral infection. ART therapy is recommended for all HIV-positive people with different regimens depending on clinical characteristics and possible interaction with other drugs.

HIV, what remains for us to do

In thirty years the HIV epidemic counts 77 million infected people and more than 35 million AIDS-related deaths. At the moment, every year there are 1.8 million new infections and 940 thousand AIDS-related deaths (data referring to 2017).

These are numbers that tell how much remains to be done in the fight against the virus, continuing to invest in development and access to therapies, but also in prevention and research. Prevention continues to be a fundamental pillar in tackling new infections, against which it is necessary to field all the weapons we have available: from tests to know one's status, to the use of condoms, to access to treatments, also in terms of pharmacological prophylaxis. But it is widely believed that to put an end to the epidemic a vaccine is needed (preventive, that is able to avoid the risk of infection in healthy people, and not therapeutic as a treatment strategy for people who are already infected). Especially in the hotspots of the infection, where the probability of spreading is higher: in the global prevalence of infection among adults of 0.8%, the region of sub-Saharan Africa reaches peaks of 4.2%.

Da:

Commenti

Posta un commento