Revealing the brain’s mysteries, one neuron at a time / Rivelando i misteri del cervello, un neurone alla volta.

Revealing the brain’s mysteries, one neuron at a time / Rivelando i misteri del cervello, un neurone alla volta.

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa+

As the seat of consciousness, the brain makes humans different from all other living creatures. Although it plays a central role in defining humanity, a precise understanding of how the brain functions still elude researchers.

Certain regions of the brain light up during certain activities – for example, the occipital lobe (one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex) serves as the brain's visual processor – and science has an appreciation of the anatomy and function of individual neurons.

In many ways, however, the brain remains an enigma, including exactly how the brain turns thoughts into actions or stores and retrieves memories.

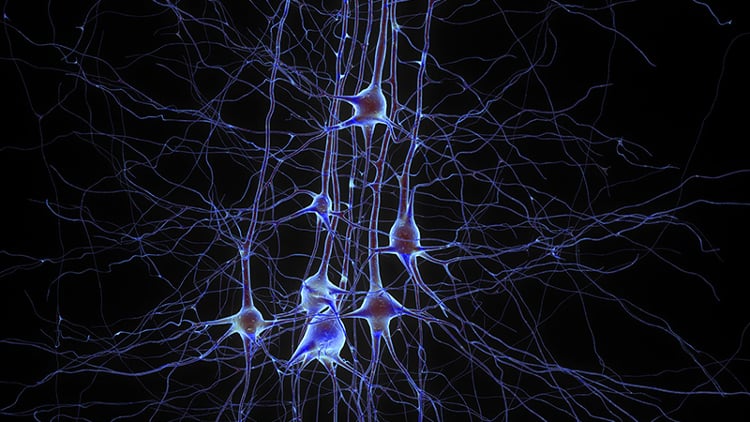

To understand how the brain works, scientists study it not only at the level of individual cells and their connections to each other – neurons and synapses – but also at the level of the entire organ in an attempt to account for its massive number of interacting cells. This is no easy task, as the brain is made up of some 100 billion neurons connected by 100 trillion synapses.

Efforts over more than a decade, however, have paved the way to a better understanding of the intricacies of the brain’s operation.

In 2013, the United States announced the Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative. That same year, the European Union kicked off its Human Brain Project. In 2014, Japan launched the Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies (Brain/MINDS) project. China’s 15-year Brain Project was given the go-ahead in 2016.

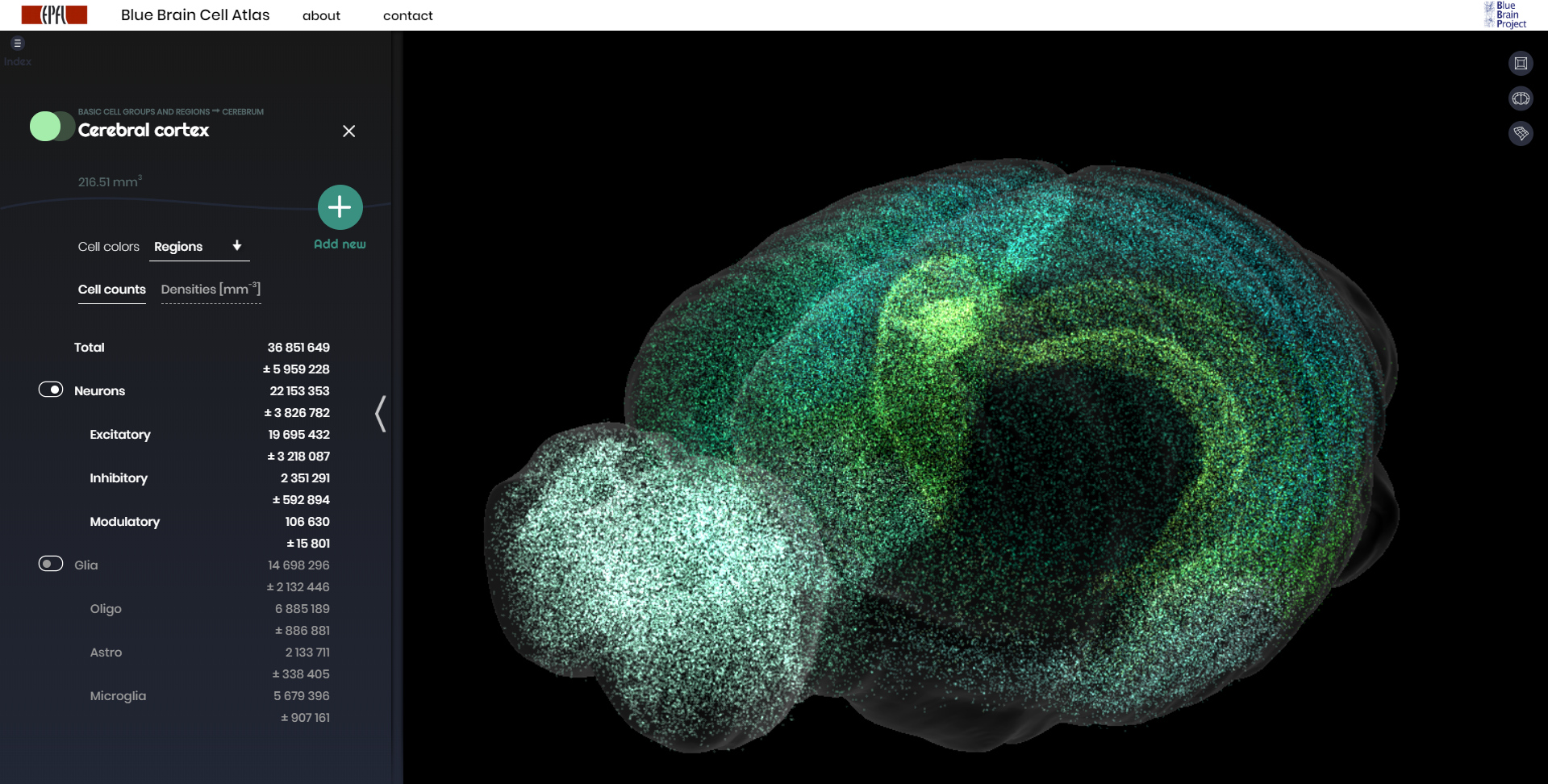

Switzerland’s Blue Brain Project, founded in 2005, predates these initiatives. Blue Brain seeks to build a fully simulated digital reconstruction of the human brain. On the path to building a complete human brain model, the project has paved the way with a replica of the small brain of the mouse.

In November 2018, the project released a digital 3D atlas of a mouse brain, showing for the first time the numbers, locations, and types of each of the over 70 million neurons in the mouse’s 737 brain regions.

Higher dimensions

Scientists funded by the Blue Brain project are also making strides in visualizing the patterns of neuron activation that occur as the brain processes information.

To accomplish this, they simulated a section of the neocortex as a network of connected nerve cells: so-called “pyramidal” neurons, the fundamental computational elements of the neocortex. Each individual neuron was modeled with its incoming and outgoing connections, taking into account the directionality of synaptic transmission in which each neuron transmits information along certain paths.

When stimulated, neurons formed functional cliques, linked groups of neurons pulsing with correlated activity. These cliques were arranged in shapes that can be thought of as geometric objects that surround holes that the researchers call cavities. The scientists analyzed the networked structure of cliques and cavities with a mathematical technique known as algebraic topology.

Remarkably, the researchers found that as neurons respond to a stimulus, the geometric shapes defined by the cliques and cavities evolve into structures with higher dimensions than the 3D world we are familiar with.

“The progression of activity through the brain resembles a multi-dimensional sandcastle that materializes out of the sand and then disintegrates,” said Mathematician Ran Levi of the University of Aberdeen.

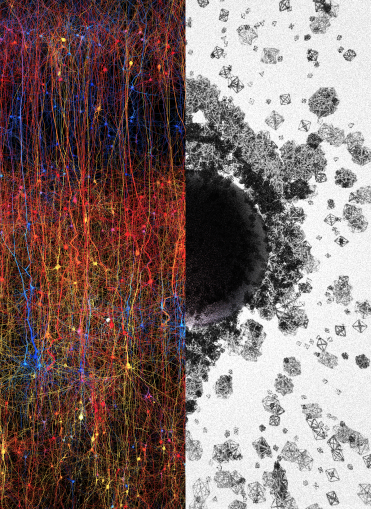

The researchers confirmed their simulated findings by carrying out experiments on rat neurons. To do that, they set up patch clamp probes to measure the electrical activity of up to 12 neurons at a time, then observed behavior similar to that found in simulations. What they found was that the real brain tissue exhibited an even greater number of cliques than was demonstrated in simulation. The researchers theorize that this is because they did not model the brain's plastic rewiring that occurs over time as an organism develops and learns, which increases organizational complexity.

Human uniqueness

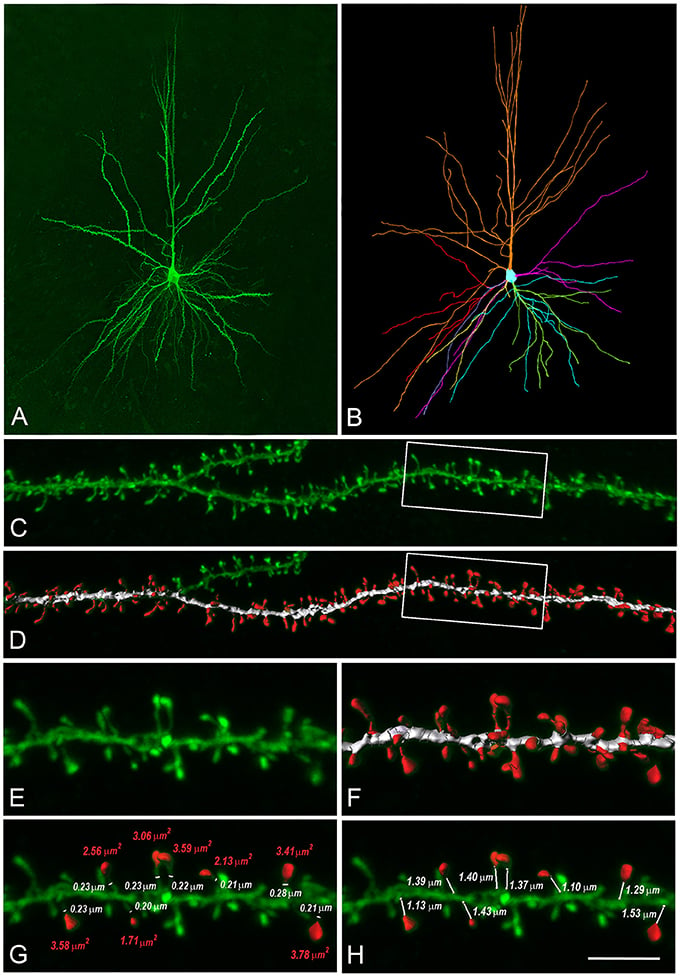

Even tissue from a rat’s brain, however, cannot reveal the human brain's full sophistication. For that, scientists carrying out a different study, building a virtual 3D model of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex with properties defined by observations obtained in biopsies of human neurons.

Differences between the neocortices of humans and rodents have been known from previous research. For example, the thicker human neocortex has a thousand times more neurons than the rat neocortex. In addition, compared to their rodent counterparts, human pyramidal neurons are physically larger, contain more branches that receive three times as many synapses – 30,000 – and feature smaller specific capacitances that facilitate easy production and transmission of electrical pulses.

The new computer simulation of human pyramidal neurons revealed new details about just how exceptional the brain cells of humans are compared to those of rodents.

“Human neurons are… fundamentally more powerful in their ability to integrate, process and store information,” said Professor Idan Segev of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

Human pyramidal neurons receive three times as many synapses as those of rats. They also can handle almost twice as many pulses of voltage traveling from the dendrite to the cell body – so-called local dendritic spikes – at the same time.

Moreover, unlike rat neurons, human neurons provide more than a basic linear sum of the electrical signals they receive. Instead, human neurons non-linearly integrate signals in branches of their dendrites (a short branched extension of a nerve cell, along which impulses received from other cells at synapses are transmitted to the cell body) before summing them up to produce an output at the axon – akin to a two-layer neural network. By comparison, rodent neurons are limited to the signal-processing capabilities of a one-layer neural network. As a result, human pyramidal neurons can store almost four times more information as to their rodent equivalents.

Full-brain simulation

Studies like these are shedding light on the brain’s function. But to truly understand how it works, a complete simulation of all of the brain’s billions of neurons and trillions of synapses is needed. To date, the most advanced brain simulation software running on the fastest supercomputers is only capable of simulating about 1% of the brain.

Instead of modeling the brain in software running on traditional supercomputers, which lack the power to fully simulate the brain, some scientists are developing neuromorphic computers. These machine's architectural design takes their inspiration from biological brains.

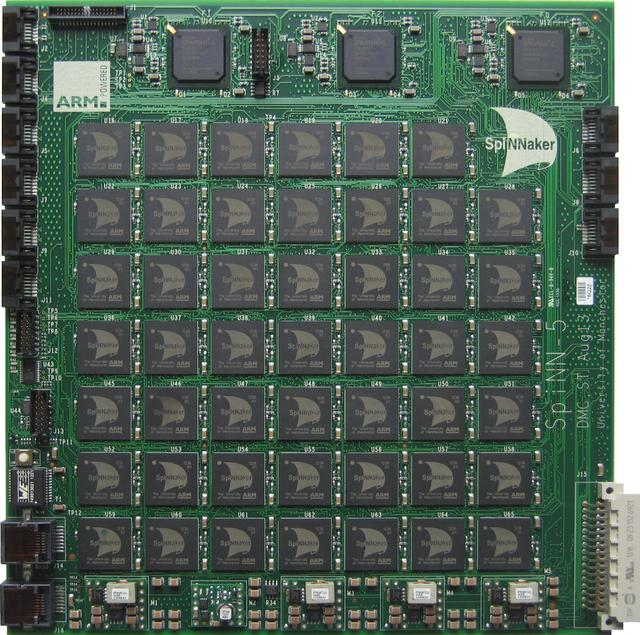

Researchers funded by the Human Brain Project are advancing a neuromorphic computer called SpiNNaker (Spiking Neural Network Architecture), made up of more than a half-million ARM processing cores (a family of reduced instruction set computing architectures for computer processors) contained on 600 circuit boards.

In a study, scientists put to work 1% of the machine’s total capacity to model the full density of cells in 1 mm2 of the cortex – about 80,000 neurons and 300 million synapses – with similar speed and power efficiency as a software simulator known as Neural Simulation Tool.

In the future, optimized instruction sets and scaled-up hardware could allow SpiNNaker to come closer to a full simulation of the human brain than ever before.

Even if SpiNNaker eventually is able to represent every one of the brain's neurons and synapses, the simulation will need to advance beyond its simplified point-neuron model with static spiking currents to take into account complexities such as the effects of conductance and plasticity.

For now, a full picture of the brain’s operation – and, thus, of humans – remains locked in complexity. Researchers are hard at work, steadily breaking down that barrier to reveal the brain’s mysteries.

ITALIANO

Alcune regioni del cervello si illuminano durante certe attività - per esempio, il lobo occipitale (uno dei quattro lobi principali della corteccia cerebrale) funge da processore visivo del cervello - e la scienza ha un apprezzamento dell'anatomia e della funzione dei singoli neuroni.

In molti modi, tuttavia, il cervello rimane un enigma, compreso esattamente come il cervello trasforma i pensieri in azioni o memorizza e recupera i ricordi.

Per capire come funziona il cervello, gli scienziati lo studiano non solo a livello delle singole cellule e delle loro connessioni l'un l'altro - neuroni e sinapsi - ma anche a livello dell'intero organo nel tentativo di spiegare il suo enorme numero di cellule interagenti . Non è un compito facile, poiché il cervello è composto da circa 100 miliardi di neuroni collegati da 100 trilioni di sinapsi.

Gli sforzi per oltre un decennio, tuttavia, hanno spianato la strada a una migliore comprensione delle complessità del funzionamento del cervello.

Nel 2013, gli Stati Uniti hanno annunciato l'iniziativa Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN). Quello stesso anno, l'Unione Europea ha dato il via al suo progetto Human Brain. Nel 2014, il Giappone ha lanciato il progetto Brain Mapping di Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies (Brain / MINDS). Nel 2015 il Brain Project della Cina ha ricevuto il via libera.

Il progetto Blue Brain della Svizzera, fondato nel 2005, precede queste iniziative. Blue Brain cerca di costruire una ricostruzione digitale completamente simulata del cervello umano. Sulla strada per costruire un modello completo di cervello umano, il progetto ha aperto la strada con una replica del piccolo cervello del topo.

Nel novembre 2018, il progetto ha rilasciato un atlante digitale 3D di un cervello di topo, che mostra per la prima volta i numeri, le posizioni e i tipi di ciascuno degli oltre 70 milioni di neuroni nelle 737 regioni del cervello del topo.

Dimensioni superiori

Gli scienziati finanziati dal progetto Blue Brain stanno anche facendo passi avanti nella visualizzazione dei modelli di attivazione dei neuroni che si verificano mentre il cervello elabora le informazioni.

Per ottenere ciò, hanno simulato una sezione della neocorteccia come una rete di cellule nervose connesse: i cosiddetti neuroni "piramidali", gli elementi computazionali fondamentali della neocorteccia. Ogni singolo neurone è stato modellato con le sue connessioni in entrata e in uscita, tenendo conto della direzionalità della trasmissione sinaptica in cui ciascun neurone trasmette informazioni lungo determinati percorsi.

Quando stimolati, i neuroni formavano cricche funzionali, gruppi collegati di neuroni che pulsavano con attività correlata. Queste cricche erano disposte in forme che possono essere pensate come oggetti geometrici che circondano buchi che i ricercatori chiamano cavità. Gli scienziati hanno analizzato la struttura in rete di cricche e cavità con una tecnica matematica nota come topologia algebrica.

Sorprendentemente, i ricercatori hanno scoperto che quando i neuroni rispondono a uno stimolo, le forme geometriche definite dalle cricche e dalle cavità si evolvono in strutture con dimensioni superiori rispetto al mondo 3D con cui abbiamo familiarità.

"La progressione dell'attività attraverso il cervello assomiglia ad un castello di sabbia multidimensionale che si materializza dalla sabbia e poi si disintegra", ha detto il matematico Ran Levi dell'Università di Aberdeen.

I ricercatori hanno confermato i loro risultati simulati eseguendo esperimenti sui neuroni di ratto. Per fare ciò, hanno installato sonde a morsetto per misurare l'attività elettrica di un massimo di 12 neuroni alla volta, quindi hanno osservato un comportamento simile a quello riscontrato nelle simulazioni. Quello che hanno scoperto è che il vero tessuto cerebrale mostrava un numero ancora maggiore di cricche rispetto a quanto era stato dimostrato nella simulazione. I ricercatori teorizzano che questo è perché non hanno modellato il ricablaggio plastico del cervello che si verifica nel tempo mentre un organismo si sviluppa e impara, il che aumenta la complessità organizzativa.

Unicità umana

Tuttavia, anche il tessuto dal cervello di un topo non può rivelare la completa sofisticazione del cervello umano. Per questo, gli scienziati conducono uno studio diverso, costruendo un modello 3D virtuale di neuroni piramidali nella neocorteccia con proprietà definite da osservazioni ottenute in biopsie di neuroni umani.

Le differenze tra i neocortici degli umani e i roditori sono state note da precedenti ricerche. Ad esempio, la neocorteccia umana più spessa ha un migliaio di volte più neuroni rispetto alla neocorteccia di ratto. Inoltre, rispetto ai loro omologhi roditori, i neuroni piramidali umani sono fisicamente più grandi, contengono più rami che ricevono tre volte più sinapsi - 30.000 - e presentano capacità specifiche più piccole che facilitano la produzione e la trasmissione di impulsi elettrici.

La nuova simulazione al computer dei neuroni piramidali umani ha rivelato nuovi dettagli su quanto siano eccezionali le cellule cerebrali degli esseri umani rispetto a quelle dei roditori.

"I neuroni umani sono ... fondamentalmente più potenti nella loro capacità di integrare, elaborare e immagazzinare informazioni", ha affermato il professor Idan Segev dell'Università Ebraica di Gerusalemme, Israele.

I neuroni piramidali umani ricevono tre volte più sinapsi di quelle dei ratti. Possono anche gestire quasi il doppio degli impulsi di tensione che viaggiano dalla dendrite al corpo cellulare - i cosiddetti picchi dendritici locali - allo stesso tempo.

Inoltre, a differenza dei neuroni di ratto, i neuroni umani forniscono più di una somma lineare di base dei segnali elettrici che ricevono. Invece, i neuroni umani integrano non linearmente i segnali nei rami dei loro dendriti (una breve estensione ramificata di una cellula nervosa, lungo la quale gli impulsi ricevuti da altre cellule sinapsi vengono trasmessi al corpo cellulare) prima di sommarli per produrre un output al assone - simile a una rete neurale a due strati. In confronto, i neuroni roditori sono limitati alle capacità di elaborazione del segnale di una rete neurale monostrato. Di conseguenza, i neuroni piramidali umani possono memorizzare quasi quattro volte più informazioni sui loro equivalenti roditori.

Simulazione completa del cervello

Studi come questi stanno facendo luce sulla funzione del cervello. Ma per capire veramente come funziona, è necessaria una simulazione completa di tutti i miliardi di neuroni del cervello e trilioni di sinapsi. Ad oggi, il più avanzato software di simulazione cerebrale eseguito sui supercomputer più veloci è in grado di simulare solo l'1% del cervello.

Invece di modellare il cervello nel software che funziona su supercomputer tradizionali, che non hanno il potere di simulare completamente il cervello, alcuni scienziati stanno sviluppando computer neuromorfici. La progettazione architettonica di queste macchine si ispira ai cervelli biologici.

I ricercatori finanziati dal Progetto Cervello Umano stanno facendo avanzare un computer neuromorfico chiamato SpiNNaker (Spiking Neural Network Architecture), costituito da oltre mezzo milione di core di elaborazione ARM (una famiglia di istruzioni di calcolo ridotte per architetture computerizzate) contenute in 600 circuiti stiro.

In uno studio, gli scienziati hanno messo a lavorare l'1% della capacità totale della macchina per modellare la densità completa delle cellule in 1 mm2 della corteccia - circa 80.000 neuroni e 300 milioni di sinapsi - con velocità ed efficienza energetica simili a quelle di un simulatore di software noto come Neural Strumento di simulazione.

In futuro, un gruppo di istruzioni ottimizzati e hardware potenziato potrebbero consentire a SpiNNaker di avvicinarsi a una simulazione completa del cervello umano come mai prima d'ora.

Anche se SpiNNaker alla fine è in grado di rappresentare tutti i neuroni e le sinapsi del cervello, la simulazione dovrà andare oltre il suo modello semplificato di neuroni puntuali con correnti di spillo statiche per tener conto delle complessità come gli effetti della conduttanza e della plasticità.

Per ora, un quadro completo dell'operazione del cervello - e, quindi, degli umani - rimane bloccato nella complessità. I ricercatori sono al lavoro, abbattendo costantemente quella barriera per rivelare i misteri del cervello.

Da:

Commenti

Posta un commento