Alzheimer’s may scramble metabolism’s connection to sleep / Il morbo di Alzheimer può confondere la connessione del metabolismo con il sonno

Alzheimer’s may scramble metabolism’s connection to sleep / Il morbo di Alzheimer può confondere la connessione del metabolismo con il sonno

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

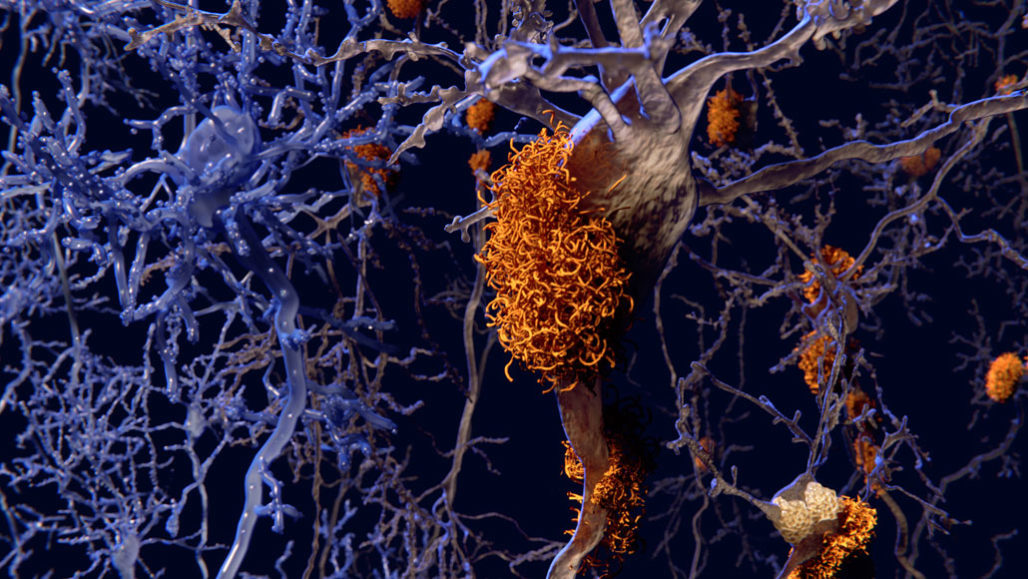

Sticky globs of amyloid-beta protein (brown in this illustration), a key sign of Alzheimer’s disease, alter how mice respond to changes in blood sugar, a study finds. / Uno studio rileva che i globuli appiccicosi della proteina beta-amiloide (marrone in questa figura), un segno chiave della malattia di Alzheimer, alterano il modo in cui i topi rispondono ai cambiamenti di zucchero nel sangue.

SELVANEGRA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Mice with signs of the disease respond abnormally to blood sugar changes

Wide swings in blood sugar can mess with sleep. Food’s relationship with sleep gets even more muddled when signs of Alzheimer’s disease are present, a study of mice suggests.

The results, presented in a news briefing October 20 at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, show that Alzheimer’s disease is not confined to the brain. “Your head is attached to your body,” says neuroscientist Shannon Macauley of Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C. Metabolism, sleep and brain health “don’t happen in isolation,” she says.

Along with Caitlin Carroll, also of Wake Forest, Macauley and coauthors rigged up a way to simultaneously measure how much sugar the brain consumes, the rate of nerve cell activity and how much time mice spend asleep. Injections of glucose into the blood led to changes in the brain: a burst of metabolism, a bump in nerve cell activity and more time spent awake. “It’s like giving a kid a lollipop,” Macauley says. “They’re going to run around in a circle.”

But a dip in blood sugar, caused by insulin injections, also led to more nerve cell action and more wakefulness. “You can have it go up high or go down low, and it was just really bad either way,” Macauley says.

Researchers did similar analyses in mice genetically engineered to have one of two key signs of Alzheimer’s. Some of these mice had clumps of amyloid-beta protein between nerve cells, while others had tangles of a protein called tau inside nerve cells.

Both groups of mice had abnormal reactions to high or low blood sugar. But those reactions depended on whether amyloid-beta or tau was in their brains. In mice with amyloid plaques, higher blood sugar led to a slight rise in brain metabolism, but not nearly as much as in a normal mouse. In mice with lots of tau, however, high blood sugar didn’t increase brain metabolism. In both cases, nerve cell activity no longer had big responses to blood sugar.

The two kinds of mice “respond to the same change in the blood sugar very, very differently,” Macauley says. A-beta and tau “might be affecting the sleep-wake circuit in very different ways, and we’re trying to understand that.”

Capturing this second-by-second action in mice brains is “beautiful work,” says neuroscientist Steve Barger of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. The data “are really exquisite, in my opinion.”

Still, Barger cautions that mice don’t capture all aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. Some of the new findings come from mice engineered to make lots of A-beta quickly in their brains. That is “quite distinct from the way that most people get Alzheimer’s disease,” Barger cautioned.

But hints from humans also point to complex relationships between sleep and Alzheimer’s (SN: 8/16/19). Study coauthor David Holtzman, a neurologist and neuroscientist at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has found that sleep begins to suffer in people with Alzheimer’s disease before other symptoms appear. Those results suggest that “sleep-wake centers and other parts of the brain are being damaged by Alzheimer’s pathology,” he says.

ITALIANO

I topi con segni della malattia rispondono in modo anomalo ai cambiamenti di zucchero nel sangue

Ampie oscillazioni di zucchero nel sangue possono rovinare il sonno. La relazione del cibo con il sonno diventa ancora più confusa quando sono presenti segni della malattia di Alzheimer, suggerisce uno studio sui topi.

I risultati, presentati in una conferenza stampa del 20 ottobre durante l'incontro annuale della Society for Neuroscience, mostrano che la malattia di Alzheimer non si limita al cervello. "La tua testa è attaccata al tuo corpo", afferma la neuroscienziata Shannon Macauley della Wake Forest School of Medicine di Winston-Salem, New York. Il metabolismo, il sonno e la salute del cervello "non avvengono in isolamento", afferma.

Insieme a Caitlin Carroll, anche di Wake Forest, Macauley e coautori hanno escogitato un modo per misurare simultaneamente quanto zucchero consuma il cervello, il tasso di attività delle cellule nervose e quanto tempo i topi trascorrono dormendo. Le iniezioni di glucosio nel sangue hanno portato a cambiamenti nel cervello: un'esplosione di metabolismo, un aumento dell'attività delle cellule nervose e più tempo trascorso sveglio. "È come dare a un bambino un lecca-lecca", dice Macauley. "Stanno andando a correre in cerchio."

Ma un calo della glicemia, causato dalle iniezioni di insulina, ha portato anche a una maggiore azione delle cellule nervose e a una maggiore veglia. "Puoi farlo salire o scendere, ed è stato davvero brutto in entrambi i casi", dice Macauley.

I ricercatori hanno fatto analisi simili nei topi geneticamente modificati per avere uno dei due segni chiave dell'Alzheimer. Alcuni di questi topi avevano gruppi di proteina beta-amiloide tra le cellule nervose, mentre altri avevano grovigli di una proteina chiamata tau all'interno delle cellule nervose.

Entrambi i gruppi di topi hanno avuto reazioni anomale a glicemia alta o bassa. Ma quelle reazioni dipendevano dal fatto che l'amiloide-beta o la tau fossero nel loro cervello. Nei topi con placche amiloidi, un aumento degli zuccheri nel sangue ha portato a un leggero aumento del metabolismo cerebrale, ma non tanto quanto in un topo normale. Nei topi con molta tau, tuttavia, la glicemia alta non ha aumentato il metabolismo cerebrale. In entrambi i casi, l'attività delle cellule nervose non ha più avuto grandi risposte allo zucchero nel sangue.

I due tipi di topi "rispondono allo stesso cambiamento di zucchero nel sangue in modo molto, molto diverso", dice Macauley. A-beta e tau "potrebbero influenzare il circuito sonno-veglia in modi molto diversi, e stiamo cercando di capirlo."

Catturare questa azione secondo per secondo nel cervello dei topi è un "bel lavoro", afferma il neuroscienziato Steve Barger dell'Università dell'Arkansas per le scienze mediche a Little Rock. I dati "sono davvero squisiti, secondo me".

Tuttavia, Barger avverte che i topi non catturano tutti gli aspetti della malattia di Alzheimer. Alcune delle nuove scoperte provengono da topi progettati per produrre rapidamente A-beta nel cervello. Questo è "abbastanza distinto dal modo in cui molte persone contraggono la malattia di Alzheimer", ha ammonito Barger.

Ma i suggerimenti degli umani indicano anche relazioni complesse tra sonno e morbo di Alzheimer (SN: 16/8/19). Il coautore dello studio David Holtzman, neurologo e neuroscienziato della Washington University School of Medicine di St. Louis, ha scoperto che il sonno inizia a soffrire nelle persone con malattia di Alzheimer prima che compaiano altri sintomi. Questi risultati suggeriscono che "i centri di veglia e altre parti del cervello sono stati danneggiati dalla patologia dell'Alzheimer", afferma.

Da:

Commenti

Posta un commento