Exploring the Latest in CRISPR and Stem Cell Research / Esplorare le ultime novità nella ricerca sulle cellule staminali e CRISPR

Exploring the Latest in CRISPR and Stem Cell Research / Esplorare le ultime novità nella ricerca sulle cellule staminali e CRISPR

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

Since the gene-editing potential of CRISPR systems was realized in 2013, they have been utilized in laboratories across the world for a wide variety of applications. When this gene-editing power is harnessed with the proliferative potential of stem cells, scientists level up their understanding of cell biology, human genetics and the future potential of medicine.

Thus far, the feasibility to edit stem cells using CRISPR technology has been demonstrated in two key areas: modeling and investigating human cell states and human diseases, and regenerative medicine. However, this has not been without challenges.

In this article, we explore some of the latest research in these spaces and the approaches that scientists are adopting to overcome these challenges.

Deciphering cell-specific gene expression using CRISPRi in iPSC-derived neurons

Deploying CRISPR technology in iPSCs has been notoriously challenging, as Martin Kampmann, of the Kampmann lab at the University of California San Francisco, says: "CRISPR introduces DNA breaks, which can be toxic for iPSCs, since these cells have a highly active DNA damage response." To overcome the issue of toxicity, as a postdoc in the lab of Professor Jonathan Weissman, Kampmann co-invented a tool known as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), where the DNA cutting ability of CRISPR/Cas9 is disabled. The "dead" Cas9 (or, dCas9) is still recruited to DNA as directed by a single guide RNA. It can therefore operate as a recruitment platform to target protein domains of interest to specific places in the genome.

CRISPRi permits gene repression at the transcription level, as opposed to RNAi which controls genes at the mRNA level. This allows researchers to repress certain genes within stem cells and decipher their function. Kampmann explains: "For CRISPRi, we target a transcriptional repressor domain (the KRAB domain) to the transcription start site of genes to repress their expression. This knockdown approach is highly effective and lacks the notorious off-target effects of RNAi-based gene knockdown."

In a study published just last month, Kampmann's laboratory adopted a CRISPRi-based platform to conduct genetic screens in human neurons derived from iPSCs: "CRISPR-based genetic screens can reveal mechanisms by which these mutations cause cellular defects, and uncover cellular pathways we can target to correct those defects. Such pathways are potential therapeutic targets."

"We expressed the CRISPRi machinery (dCas9-KRAB) from a safe-harbor locus in the genome, where it is not silenced during neuronal differentiation. We also developed a CRISPRi construct with degrons, stability of which is controlled by small molecules. This way, we can induce CRISPRi knockdown of genes of interest at different times during neuronal differentiation."

Thus far, the feasibility to edit stem cells using CRISPR technology has been demonstrated in two key areas: modeling and investigating human cell states and human diseases, and regenerative medicine. However, this has not been without challenges.

In this article, we explore some of the latest research in these spaces and the approaches that scientists are adopting to overcome these challenges.

Deciphering cell-specific gene expression using CRISPRi in iPSC-derived neurons

Deploying CRISPR technology in iPSCs has been notoriously challenging, as Martin Kampmann, of the Kampmann lab at the University of California San Francisco, says: "CRISPR introduces DNA breaks, which can be toxic for iPSCs, since these cells have a highly active DNA damage response." To overcome the issue of toxicity, as a postdoc in the lab of Professor Jonathan Weissman, Kampmann co-invented a tool known as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), where the DNA cutting ability of CRISPR/Cas9 is disabled. The "dead" Cas9 (or, dCas9) is still recruited to DNA as directed by a single guide RNA. It can therefore operate as a recruitment platform to target protein domains of interest to specific places in the genome.

CRISPRi permits gene repression at the transcription level, as opposed to RNAi which controls genes at the mRNA level. This allows researchers to repress certain genes within stem cells and decipher their function. Kampmann explains: "For CRISPRi, we target a transcriptional repressor domain (the KRAB domain) to the transcription start site of genes to repress their expression. This knockdown approach is highly effective and lacks the notorious off-target effects of RNAi-based gene knockdown."

In a study published just last month, Kampmann's laboratory adopted a CRISPRi-based platform to conduct genetic screens in human neurons derived from iPSCs: "CRISPR-based genetic screens can reveal mechanisms by which these mutations cause cellular defects, and uncover cellular pathways we can target to correct those defects. Such pathways are potential therapeutic targets."

"We expressed the CRISPRi machinery (dCas9-KRAB) from a safe-harbor locus in the genome, where it is not silenced during neuronal differentiation. We also developed a CRISPRi construct with degrons, stability of which is controlled by small molecules. This way, we can induce CRISPRi knockdown of genes of interest at different times during neuronal differentiation."

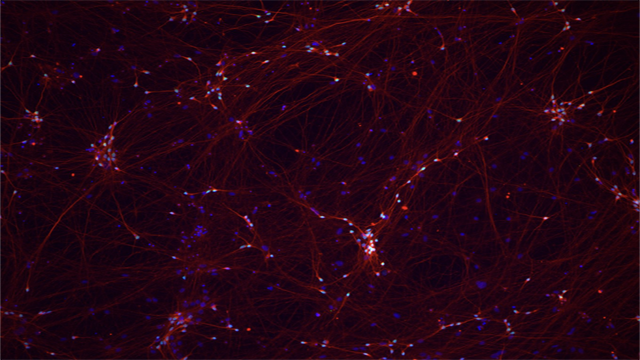

Image: iPSC-derived neurons. / Immagine: neuroni derivati da iPSC. Credit: Kampmann Lab, UCSF.

Previous CRISPR-based screens have focused on cancer cell lines or stem cells rather than healthy human cells, thus limiting potential insights into the cell-type-specific roles of human genes. The researchers opted to screen in iPSC-derived neurons as genomic screens have revealed mechanisms of selective vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases, and convergent mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders.

The large-scale CRISPRi screen uncovered genes that were essential for both neurons and iPSCs yet caused different transcriptomic phenotypes when knocked down. "For me, one of the most exciting findings was the broadly expressed genes that we think of as housekeeping genes had different functions in iPSCs versus neurons. This may explain why mutations in housekeeping genes can affect different cell types and tissues in the body in very different ways," says Kampmann. For example, knockdown of the E1 ubiquitin activating enzyme, UBA1, resulted in neuron-specific induction of a large number of genes, including endoplasmic reticulum chaperone HSPA5 and HSP90B1.

These results suggest that comprised UBA1 triggers a proteotoxic stress response in neurons but not iPSCs – aligning with the suggested role of UBA1 in several neurodegenerative diseases. The authors note: "Parallel genetic screens across the full gamut of human cell types may systematically uncover context-specific roles of human genes, leading to a deeper mechanistic understanding of how they control human biology and disease."

Previous CRISPR-based screens have focused on cancer cell lines or stem cells rather than healthy human cells, thus limiting potential insights into the cell-type-specific roles of human genes. The researchers opted to screen in iPSC-derived neurons as genomic screens have revealed mechanisms of selective vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases, and convergent mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders.

The large-scale CRISPRi screen uncovered genes that were essential for both neurons and iPSCs yet caused different transcriptomic phenotypes when knocked down. "For me, one of the most exciting findings was the broadly expressed genes that we think of as housekeeping genes had different functions in iPSCs versus neurons. This may explain why mutations in housekeeping genes can affect different cell types and tissues in the body in very different ways," says Kampmann. For example, knockdown of the E1 ubiquitin activating enzyme, UBA1, resulted in neuron-specific induction of a large number of genes, including endoplasmic reticulum chaperone HSPA5 and HSP90B1.

These results suggest that comprised UBA1 triggers a proteotoxic stress response in neurons but not iPSCs – aligning with the suggested role of UBA1 in several neurodegenerative diseases. The authors note: "Parallel genetic screens across the full gamut of human cell types may systematically uncover context-specific roles of human genes, leading to a deeper mechanistic understanding of how they control human biology and disease."

Video credit: UCSF.

Developing and testing cell-based therapies for human disease using CRISPR

Several laboratories across the globe are in an apparent race to develop the first clinically relevant, efficacious and safe cell-based therapy utilizing CRISPR gene-editing technology.

Whilst a plethora of literature demonstrates the efficacy of CRISPR in editing the genome of mammalian cells in vitro, for in vivo application, particularly in humans, rigorous long-term testing of safety outcomes is required. This month, researchers from the laboratory of Hongkui Deng, a Professor at Peking University in Beijing, published a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine. The paper outlined their world-first study in which they transplanted allogenic CRISPR-edited stem cells into a human patient with HIV.

The rationale for the study stems back to the "Berlin patient", referring to Timothy Ray Brown who is one of very few individuals in the world that has been cured of HIV. Brown received a bone marrow transplant from an individual that carries a mutant form of the CCR5 gene. Under normal conditions, the CCR5 gene encodes a receptor on the surface of white blood cells. This receptor effectively provides a passageway for the HIV to enter cells. In individuals with two copies of the CCR5 mutation, the receptor is distorted and restricts strains of HIV from entering cells.

Deng and colleagues used CRISPR to genetically edit donor hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) to carry either a CCR5 insertion or deletion. They were able to achieve this with an efficiency of 17.8%, indicated by genetic sequencing. The CRISPR-edited HSPCs were then transplanted into an HIV patient who also had leukaemia and required a bone-marrow transplant, with the goal being to eradicate HIV.

"The study was designed to assess the safety and feasibility of the transplantation of CRISPR–Cas9–modified HSPCs into HIV-1–positive patients with hematologic cancer," Deng says. He continues: "The success of genome editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells was evaluated in three aspects including editing persistence, specificity and efficiency in long-term engrafting HSPCs." Long-term monitoring of the HIV patient found that, 19 months after transplantation, the CRISPR-edited stem cells were alive – however, they only comprised five to eight percent of total stem cells. Thus, the patient is still infected with HIV.

Despite the seemingly low efficiency in long-term survival, the researchers were encouraged by the results from the safety assessment aspect of the study: "Previously reported hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells-based gene therapies were less effective because of random integration of exogenous DNA into the genome, which sometimes induced acute immune responses or neoplasia," Deng says. "The apparent absence of clinical adverse events from gene editing and off-target effects in this study provides preliminary support for the safety of this gene-editing approach."

"To further clarify the anti-HIV effect of CCR5-ablated HSPCs, it will be essential to increase the gene-editing efficiency of our CRISPR–Cas9 system and improve the transplantation protocol," says Deng.

The marrying of CRISPR gene-editing and stem cell research isn't just bolstering therapeutic developments in HIV. An ongoing clinical trial is evaluating the safety and efficacy of autologous CRISPR-Cas9 modified CD34+ HSPCs for the treatment of transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia, a genetic blood disorder that causes hemoglobin deficiency.

The therapeutic approach – known as CTX001 – involves extracting a patient’s HSPCs and using CRISPR-Cas9 to modify the cells at the erythroid lineage-specific enhancer of the BCL11A gene. The genetically modified cells are then infused back into the patient's body, where they produce large numbers of red blood cells that contain fetal hemoglobin. Currently no results are available, but reports confirm that participants have been recruited on to the trial.

A bright future

Our understanding of cell biology and diseased states has been majorly enhanced by the combined use of CRISPR technology and stem cells. Whilst this article has focused on current study examples, Zhang et al.'s recent review provides a comprehensive view of the field and insights provided by earlier studies.

In such review, the authors comment "Undoubtedly, the CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing system has revolutionarily changed the fundamental and translational stem cell research." Solutions are still required to resolve the notorious off-target effects of CRISPR technology, to improve the editing efficiency as outlined by Deng and to exploit novel delivery strategies that are safe for clinical stem cell studies.

Nonetheless, the future looks bright for CRISPR and stemcell-based research. In their review published this month, Bukhari and Müller say, "We expect CRISPR technology to be increasingly used in iPSC-derived organoids: protein function(subcellular localization, cell type specific expression, cleavage, and degradation) can be studied in developing as well as adult organoids under their native conditions."

Several laboratories across the globe are in an apparent race to develop the first clinically relevant, efficacious and safe cell-based therapy utilizing CRISPR gene-editing technology.

Whilst a plethora of literature demonstrates the efficacy of CRISPR in editing the genome of mammalian cells in vitro, for in vivo application, particularly in humans, rigorous long-term testing of safety outcomes is required. This month, researchers from the laboratory of Hongkui Deng, a Professor at Peking University in Beijing, published a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine. The paper outlined their world-first study in which they transplanted allogenic CRISPR-edited stem cells into a human patient with HIV.

The rationale for the study stems back to the "Berlin patient", referring to Timothy Ray Brown who is one of very few individuals in the world that has been cured of HIV. Brown received a bone marrow transplant from an individual that carries a mutant form of the CCR5 gene. Under normal conditions, the CCR5 gene encodes a receptor on the surface of white blood cells. This receptor effectively provides a passageway for the HIV to enter cells. In individuals with two copies of the CCR5 mutation, the receptor is distorted and restricts strains of HIV from entering cells.

Deng and colleagues used CRISPR to genetically edit donor hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) to carry either a CCR5 insertion or deletion. They were able to achieve this with an efficiency of 17.8%, indicated by genetic sequencing. The CRISPR-edited HSPCs were then transplanted into an HIV patient who also had leukaemia and required a bone-marrow transplant, with the goal being to eradicate HIV.

"The study was designed to assess the safety and feasibility of the transplantation of CRISPR–Cas9–modified HSPCs into HIV-1–positive patients with hematologic cancer," Deng says. He continues: "The success of genome editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells was evaluated in three aspects including editing persistence, specificity and efficiency in long-term engrafting HSPCs." Long-term monitoring of the HIV patient found that, 19 months after transplantation, the CRISPR-edited stem cells were alive – however, they only comprised five to eight percent of total stem cells. Thus, the patient is still infected with HIV.

Despite the seemingly low efficiency in long-term survival, the researchers were encouraged by the results from the safety assessment aspect of the study: "Previously reported hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells-based gene therapies were less effective because of random integration of exogenous DNA into the genome, which sometimes induced acute immune responses or neoplasia," Deng says. "The apparent absence of clinical adverse events from gene editing and off-target effects in this study provides preliminary support for the safety of this gene-editing approach."

"To further clarify the anti-HIV effect of CCR5-ablated HSPCs, it will be essential to increase the gene-editing efficiency of our CRISPR–Cas9 system and improve the transplantation protocol," says Deng.

The marrying of CRISPR gene-editing and stem cell research isn't just bolstering therapeutic developments in HIV. An ongoing clinical trial is evaluating the safety and efficacy of autologous CRISPR-Cas9 modified CD34+ HSPCs for the treatment of transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia, a genetic blood disorder that causes hemoglobin deficiency.

The therapeutic approach – known as CTX001 – involves extracting a patient’s HSPCs and using CRISPR-Cas9 to modify the cells at the erythroid lineage-specific enhancer of the BCL11A gene. The genetically modified cells are then infused back into the patient's body, where they produce large numbers of red blood cells that contain fetal hemoglobin. Currently no results are available, but reports confirm that participants have been recruited on to the trial.

A bright future

Our understanding of cell biology and diseased states has been majorly enhanced by the combined use of CRISPR technology and stem cells. Whilst this article has focused on current study examples, Zhang et al.'s recent review provides a comprehensive view of the field and insights provided by earlier studies.

In such review, the authors comment "Undoubtedly, the CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing system has revolutionarily changed the fundamental and translational stem cell research." Solutions are still required to resolve the notorious off-target effects of CRISPR technology, to improve the editing efficiency as outlined by Deng and to exploit novel delivery strategies that are safe for clinical stem cell studies.

Nonetheless, the future looks bright for CRISPR and stemcell-based research. In their review published this month, Bukhari and Müller say, "We expect CRISPR technology to be increasingly used in iPSC-derived organoids: protein function(subcellular localization, cell type specific expression, cleavage, and degradation) can be studied in developing as well as adult organoids under their native conditions."

ITALIANO

Dal momento che il potenziale di modifica genetica dei sistemi CRISPR è stato realizzato nel 2013, sono stati utilizzati nei laboratori di tutto il mondo per un'ampia varietà di applicazioni. Quando questo potere di modifica genetica viene sfruttato con il potenziale proliferativo delle cellule staminali, gli scienziati aumentano di livello la loro comprensione della biologia cellulare, della genetica umana e del potenziale futuro della medicina.

Finora, la fattibilità di modificare le cellule staminali utilizzando la tecnologia CRISPR è stata dimostrata in due aree chiave: modellizzazione e studio degli stati cellulari e delle malattie umani e medicina rigenerativa. Tuttavia, questo non è stato senza sfide.

In questo articolo, esploriamo alcune delle ultime ricerche in questi spazi e gli approcci che gli scienziati stanno adottando per superare queste sfide.

Decifrare l'espressione genica specifica delle cellule usando CRISPRi nei neuroni derivati da iPSC

L'implementazione della tecnologia CRISPR negli iPSC è stata notoriamente impegnativa, come afferma Martin Kampmann, del laboratorio Kampmann dell'Università della California di San Francisco: "CRISPR introduce rotture di DNA, che possono essere tossiche per gli iPSC, poiché queste cellule hanno un danno al DNA molto attivo risposta." Per superare il problema della tossicità, come postdoc nel laboratorio del professor Jonathan Weissman, Kampmann ha co-inventato uno strumento noto come interferenza CRISPR (CRISPRi), in cui la capacità di taglio del DNA di CRISPR / Cas9 è disabilitata. Il "morto" Cas9 (o, dCas9) è ancora reclutato nel DNA come diretto da una singola guida RNA. Può quindi operare come una piattaforma di reclutamento per indirizzare domini proteici di interesse verso luoghi specifici del genoma.

CRISPRi consente la repressione genica a livello di trascrizione, a differenza dell'RNAi che controlla i geni a livello di mRNA. Ciò consente ai ricercatori di reprimere determinati geni all'interno delle cellule staminali e di decifrarne la funzione. Kampmann spiega: "Per CRISPRi, indirizziamo un dominio repressore trascrizionale (il dominio KRAB) al sito di inizio della trascrizione dei geni per reprimerne l'espressione. Questo approccio knockdown è altamente efficace e privo dei famigerati effetti off-target del knockdown genico basato su RNAi ".

In uno studio pubblicato proprio il mese scorso, il laboratorio di Kampmann ha adottato una piattaforma basata su CRISPRi per condurre schermi genetici nei neuroni umani derivati da iPSC: "Gli schermi genetici basati su CRISPR possono rivelare meccanismi attraverso i quali queste mutazioni causano difetti cellulari e scoprire i percorsi cellulari che possiamo obiettivo per correggere quei difetti. Tali percorsi sono potenziali obiettivi terapeutici ".

"Abbiamo espresso il meccanismo CRISPRi (dCas9-KRAB) da un locus sicuro nel genoma, dove non è messo a tacere durante la differenziazione neuronale. Abbiamo anche sviluppato un costrutto CRISPRi con degroni, la cui stabilità è controllata da piccole molecole. In questo modo , possiamo indurre il knockdown CRISPRi dei geni di interesse in momenti diversi durante la differenziazione neuronale ".

I precedenti schermi basati su CRISPR si sono concentrati sulle linee cellulari tumorali o sulle cellule staminali piuttosto che sulle cellule umane sane, limitando così potenziali approfondimenti sui ruoli specifici del tipo di cellula dei geni umani. I ricercatori hanno optato per lo screening nei neuroni derivati dall'IPSC poiché gli schermi genomici hanno rivelato meccanismi di vulnerabilità selettiva nelle malattie neurodegenerative e meccanismi convergenti nei disturbi neuropsichiatrici.

Lo schermo CRISPRi su larga scala ha scoperto geni che erano essenziali sia per i neuroni che per iPSC, ma che hanno causato diversi fenotipi trascrittomici quando abbattuti. "Per me, uno dei risultati più entusiasmanti sono stati i geni ampiamente espressi che pensiamo che i geni di pulizia abbiano diverse funzioni negli iPSC rispetto ai neuroni. Questo potrebbe spiegare perché le mutazioni dei geni di pulizia possono influenzare diversi tipi di cellule e tessuti nel corpo in modi diversi ", afferma Kampmann. Ad esempio, il knockdown dell'enzima attivatore dell'ubiquitina E1, UBA1, ha determinato l'induzione specifica del neurone di un gran numero di geni, tra cui il chaperone del reticolo endoplasmatico HSPA5 e HSP90B1.

Questi risultati suggeriscono che UBA1 compreso innesca una risposta allo stress proteotossico nei neuroni ma non iPSC - allineandosi con il ruolo suggerito di UBA1 in diverse malattie neurodegenerative. Gli autori osservano: "Schermi genetici paralleli nell'intera gamma di tipi di cellule umane possono scoprire sistematicamente ruoli specifici dei contesti dei geni umani, portando a una comprensione meccanicistica più profonda di come controllano la biologia e la malattia umana".

Sviluppare e testare terapie cellulari per le malattie umane usando CRISPR

Numerosi laboratori in tutto il mondo sono in procinto di sviluppare la prima terapia clinicamente rilevante, efficace e sicura basata su cellule che utilizza la tecnologia di editing genetico CRISPR.

Mentre una pletora di letteratura dimostra l'efficacia del CRISPR nella modifica del genoma delle cellule di mammifero in vitro, per l'applicazione in vivo, in particolare nell'uomo, sono richiesti rigorosi test a lungo termine sugli esiti della sicurezza. Questo mese, alcuni ricercatori del laboratorio di Hongkui Deng, professore alla Peking University di Pechino, hanno pubblicato un articolo sul New England Journal of Medicine. L'articolo ha delineato il loro primo studio al mondo in cui hanno trapiantato cellule staminali allogeniche modificate dal CRISPR in un paziente umano con HIV.

La logica dello studio risale al "paziente di Berlino", riferito a Timothy Ray Brown che è uno dei pochissimi individui al mondo che è stato curato dall'HIV. Brown ha ricevuto un trapianto di midollo osseo da un individuo che trasporta una forma mutante del gene CCR5. In condizioni normali, il gene CCR5 codifica un recettore sulla superficie dei globuli bianchi. Questo recettore fornisce efficacemente un passaggio per l'HIV per entrare nelle cellule. In soggetti con due copie della mutazione CCR5, il recettore è distorto e impedisce ai ceppi di HIV di entrare nelle cellule.

Deng e colleghi hanno utilizzato CRISPR per modificare geneticamente le cellule staminali e progenitrici ematopoietiche del donatore (HSPC) per effettuare un inserimento o una delezione di CCR5. Sono stati in grado di raggiungere questo obiettivo con un'efficienza del 17,8%, indicata dal sequenziamento genetico. Gli HSPC modificati dal CRISPR sono stati quindi trapiantati in un paziente affetto da HIV che aveva anche la leucemia e necessitava di un trapianto di midollo osseo, con l'obiettivo di sradicare l'HIV.

"Lo studio è stato progettato per valutare la sicurezza e la fattibilità del trapianto di HSPC modificati da CRISPR-Cas9 in pazienti HIV-1 positivi con carcinoma ematologico", afferma Deng. Continua: "Il successo dell'editing del genoma nelle cellule staminali e progenitrici ematopoietiche umane è stato valutato in tre aspetti tra cui la persistenza, la specificità e l'efficienza dell'editing negli HSPC a innesto a lungo termine". Il monitoraggio a lungo termine del paziente affetto da HIV ha riscontrato che, a 19 mesi dal trapianto, le cellule staminali modificate dal CRISPR erano vive, tuttavia comprendevano solo dal 5 all'8% delle cellule staminali totali. Pertanto, il paziente è ancora infetto dall'HIV.

Nonostante l'efficienza apparentemente bassa nella sopravvivenza a lungo termine, i ricercatori sono stati incoraggiati dai risultati dell'aspetto della valutazione della sicurezza dello studio: "Le terapie genetiche basate su cellule staminali e progenitrici ematopoietiche precedentemente riportate erano meno efficaci a causa dell'integrazione casuale del DNA esogeno in il genoma, che a volte induceva risposte immunitarie acute o neoplasia ", afferma Deng. "L'apparente assenza di eventi avversi clinici da modifica genetica ed effetti off-target in questo studio fornisce un supporto preliminare per la sicurezza di questo approccio di modifica genica."

"Per chiarire ulteriormente l'effetto anti-HIV degli HSPC ablati da CCR5, sarà essenziale aumentare l'efficienza di modifica genetica del nostro sistema CRISPR-Cas9 e migliorare il protocollo di trapianto", afferma Deng.

Il matrimonio tra la modifica del gene CRISPR e la ricerca sulle cellule staminali non sta solo rafforzando gli sviluppi terapeutici nell'HIV. Uno studio clinico in corso sta valutando la sicurezza e l'efficacia dei CD34 + HSPC modificati CRISPR-Cas9 autologhi per il trattamento della β-talassemia dipendente dalle trasfusioni, una malattia genetica del sangue che causa deficit di emoglobina.

L'approccio terapeutico - noto come CTX001 - prevede l'estrazione degli HSPC di un paziente e l'utilizzo di CRISPR-Cas9 per modificare le cellule del potenziatore specifico del lignaggio eritroide del gene BCL11A. Le cellule geneticamente modificate vengono quindi reinfuse nel corpo del paziente, dove producono un gran numero di globuli rossi che contengono emoglobina fetale. Al momento non sono disponibili risultati, ma i rapporti confermano che i partecipanti sono stati assunti per la prova.

Un futuro brillante

La nostra comprensione della biologia cellulare e degli stati malati è stata notevolmente migliorata dall'uso combinato della tecnologia CRISPR e delle cellule staminali. Mentre questo articolo si è concentrato sugli esempi di studio attuali, la recente recensione di Zhang et al. Fornisce una visione completa del campo e approfondimenti forniti da studi precedenti.

In tale recensione, gli autori commentano "Indubbiamente, il sistema di editing del genoma CRISPR / Cas9 ha cambiato radicalmente la ricerca fondamentale e traslazionale sulle cellule staminali". Sono ancora necessarie soluzioni per risolvere i famigerati effetti off-target della tecnologia CRISPR, migliorare l'efficienza di modifica come indicato da Deng e sfruttare nuove strategie di consegna sicure per gli studi clinici sulle cellule staminali.

Ciononostante, il futuro appare luminoso per la ricerca basata su CRISPR e stemcell. Nella loro recensione pubblicata questo mese, Bukhari e Müller affermano: "Ci aspettiamo che la tecnologia CRISPR sia sempre più utilizzata negli organoidi derivati dall'iPSC: la funzione proteica (localizzazione subcellulare, espressione specifica del tipo di cellula, scissione e degradazione) può essere studiata anche nello sviluppo come organoidi adulti nelle loro condizioni native. "

Da:

Commenti

Posta un commento