Forse non tutti sanno che… nessuno sa cos’è la gravità, nemmeno gli scienziati / Maybe not everyone knows that ... nobody knows what gravity is, not even scientists

Forse non tutti sanno che… nessuno sa cos’è la gravità, nemmeno gli scienziati / Maybe not everyone knows that ... nobody knows what gravity is, not even scientists

I lettori sono avvertiti: non riuscirete – ammonisce Richard Panek nell’introduzione a Il mistero sotto i nostri piedi – a sapere cosa sia la gravità. E lo fa con una sorta di gioco di parole. “Parlerò di cosa la gravità causi, e di cosa causi la gravità”, perché “nessuno sa che cosa sia la gravità, e quasi nessuno sa che nessuno sa che cosa sia la gravità. Gli scienziati fanno eccezione. Loro sanno che nessuno sa che cosa sia la gravità, perché sanno che loro stessi non sanno che cosa sia la gravità”.

La gravità non ha mai riguardato esclusivamente la fisica ma ha sempre affondato le sue radici nella metafisica e nella filosofia, tanto da essere presente nei più antichi miti della creazione che raccontano come, per una qualche colpa, gli umani siano stati scaraventati quaggiù, da una condizione privilegiata per cui si trovavano in un altrove, lassù. Nel racconto delle varie religioni, nei testi filosofici, nelle antiche concezioni scientifiche del mondo corruttibile confrontato alle sfere celesti, cristalline e pure, si cercano spiegazioni cosmologiche di quello che si vede muovere sulla Terra e di quello che si vede muovere nei cieli. Ma bisogna saper guardare, in modo tale da far nascere nuovi problemi e trovarne possibili soluzioni.

Galileo e gli esperimenti con il piano inclinato

Panek trova nella storia del pensiero, e in particolare nelle intuizioni di Galilei, Newton ed Einstein, tre fondamentali punti di svolta. I tre scienziati, ciascuno nel proprio tempo, sanno guardare le cose in modo non convenzionale e, reinterpretando fatti considerati ovvii, aprono nuove prospettive allo sviluppo delle conoscenze. Galileo, con i suoi esperimenti sul piano inclinato, cerca la matematica che descrive esattamente i moti e scopre che una sfera acquista sempre velocità durante la caduta e che, soprattutto, accelera in modo costante. Inoltre la materia a riposo permane a riposo fin quando non viene messa in moto, e la materia in moto permane in moto fin quando non viene fermata. Ma dal punto di vista di una sfera che rotola su un piano senza attrito a velocità costante, pensa Galileo, non c’e alcuna differenza tra essere in moto e non esserlo.

Newton e le orbite dei corpi celesti

Newton, che gradualmente si costruisce una matematica adatta alle sue interpretazioni, usa i termini gravità e levità per indicare la tendenza ad andare verso il basso (quando un sasso cade) e verso l’alto (quando una fiamma si innalza) e immagina che la gravità sia causata da una materia “gommosa”, “untuosa”, “di natura duttile e tenace”. Ma soprattutto, spiega Panek, Newton si domanda cosa significhi “essere in moto”: perché un pianeta non dovrebbe continuare il proprio moto in linea retta? Perché dovrebbe deviare, curvare, lasciare il percorso rettilineo per intraprenderne uno ellittico? Oltre a quello in linea retta ci deve essere un altro movimento, quello verso il basso studiato da Galileo.

Mettendo insieme il moto in avanti, inerziale, e quello verso il basso, centripeto, Newton riesce a spiegare il movimento dei pianeti lungo le loro orbite ellittiche e quello della Luna intorno alla Terra. La Luna cade verso la Terra. Ma la Terra cade verso la Luna, anche se cade al contempo verso il Sole, e il Sole cade verso la Terra, e Giove verso la Terra, verso il Sole e verso la Luna, e a loro volta anch’essi cadono verso Giove… e cosi via: tutti i corpi celesti viaggiano sulle loro linee rette mentre cadono l’uno verso l’altro. Il termine gravitazione indica, per Newton, la combinazione dei due effetti, quello inerziale e quello centripeto – l’effetto globale che noi percepiamo in forma di orbite ellittiche e di oggetti che cadono. Ma la causa rimane misteriosa. “Non sono ancora stato in grado di dedurre dai fenomeni le ragioni per queste proprietà della gravità, e non invento ipotesi”, scrive Newton, ma aggiunge: “E’ sufficiente che la gravità esista davvero e agisca secondo le leggi che abbiamo presentato”. Non c’è necessità di sapere cosa sia.

La ricerca delle cause prime

I secoli passano e il pensiero scientifico esplora altre direzioni: i pendoli che oscillano più lentamente in prossimità dell’Equatore danno indicazioni sulla forma della Terra, si predice quanto il moto di una cometa – quella di Halley – possa essere influenzato da Saturno e da Giove mentre si allontana dal Sole, si scopre che il cuore pompa sangue nel corpo in modo circolare, Lyell tenta di spiegare “i cambiamenti passati della superficie terrestre con riferimento alle cause ora in atto”, Darwin pubblica “L’origine delle specie”. La natura segue delle leggi, e tali leggi sono universali.

Si cercano le “Cause Prime” dei fenomeni nella religione o nella matematica, ma certe spiegazioni restano incomprensibili. Già ai primi del ‘900 Mach distingue tra incomprensibilità ordinaria e non ordinaria. L’esempio che usa riguarda i concetti di luce e gravità del diciassettesimo secolo. Newton pensa che la luce si propaghi sotto forma di palline, che egli chiama corpuscoli. Huygens propone di interpretare la luce come onda – un concetto, scrive Mach, “incomprensibile per Newton”. Allo stesso modo, l’idea di Newton di un’azione a distanza è “incomprensibile per Huygens”. “Ma un secolo dopo – continua Mach – le nozioni diventano conciliabili, anche per una mente comune”.

Einstein e le onde gravitazionali

Negli stessi anni, Einstein comincia a sviluppare i suoi esperimenti mentali e nota come osservatori in moto relativo uniforme possono fare affermazioni differenti sulla realtà che appare loro. Sa che la velocità della luce è finita e che non cambia nel vuoto, ma sebbene l’universo sia comprensibile a tutti nello stesso modo, ogni osservazione può essere diversa relativamente a un’altra. Come spiega Panek, Einstein vuole una teoria generale, che si applichi a oggetti in moto relativo non uniforme. I riferimenti a spazio e tempo non hanno senso – sostiene – se non si specifica relativamente a cosa. Ragionamenti e ipotesi si sviluppano nella sua mente. Come per lo spazio e il tempo “unificati” da Galileo, come il moto inerziale in linea retta e quello centripeto verso il basso “unificati” da Newton, Einstein pensa che la massa inerziale (quella che misura la resistenza di un oggetto a cambiare il suo stato di moto) e la massa gravitazionale (quella che misura la predisposizione di un oggetto a cambiare il suo stato di moto) misurino la stessa cosa.

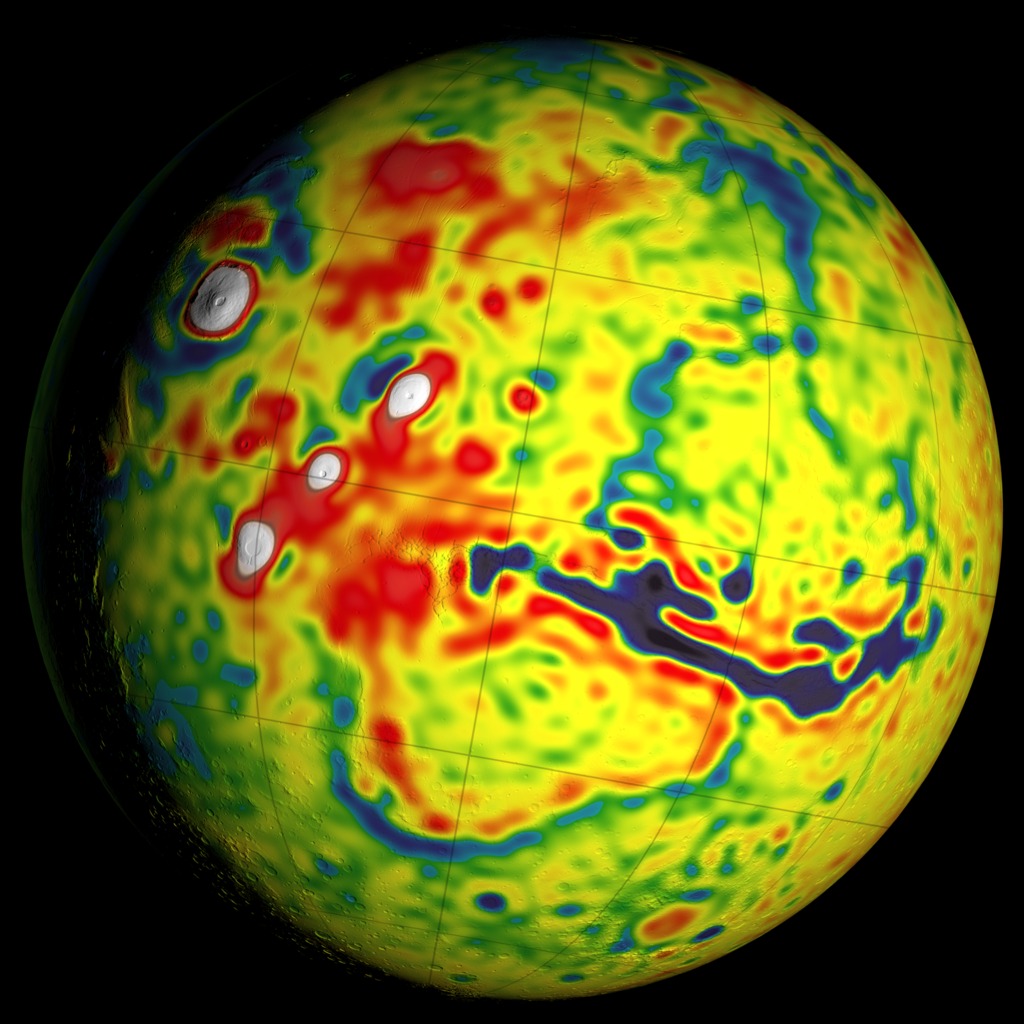

Nella fisica di Newton, la materia è attiva e si muove, mentre lo spazio è un contenitore passivo in cui avvengono scambi misteriosi tra le masse. Nella fisica di Einstein la materia è ancora attiva. Ma anche lo spazio diventa attivo: coopera con la materia per produrre ciò che noi percepiamo come effetto della gravità. La materia incurva lo spazio, lo spazio guida la materia. La “sensazione” di attrazione non è solo reciproca: è continua nello spazio e nel tempo. Einstein considera lo spazio quasi letteralmente come un fluido e pensa che l’universo si comporti come un oceano, globalmente e dinamicamente continuo. Si può osservare un’onda qui o un vortice lì, ma questi fenomeni non esistono in modo isolato. Emergono dal loro ambiente, e l’ambiente emerge da essi. La presenza di una massa crea una curvatura dello spazio, genera onde – gravitazionali– percepite, appunto come gravità e capaci di spiegare l’azione a distanza, l’“enorme assurdità” che Newton non riusciva a giustificare.

Nuovi casi di incomprensibilità ordinaria

Nella seconda metà del ‘900 la meccanica quantistica apre ai fisici nuove prospettive di ricerca, e la cosmologia si sviluppa attraverso suggestive teorie sull’origine e la struttura dell’Universo, ampliando la sua visione fino a ipotizzare possibili “multiversi” le cui interpretazioni superano finanche i limiti della incomprensibilità ordinaria. Le tradizionali concettualizzazioni dell’Universo vengono modificate e nuove rappresentazioni multimediali, come ad esempio il documentario Interstellar, visualizzano le conoscenze proponendo a un vasto pubblico immagini straordinarie di oggetti incomprensibili come i buchi neri. Al tempo stesso strumenti sensibilissimi come l’interferometro LIGO sono stati in grado di rilevare il passaggio di onde gravitazionali provocate dalla collisione tra due buchi neri in orbita l’uno intorno all’altro, e questi risultati generano teorie che rappresentano nuovi casi di “incomprensibilità ordinaria”.

Non è facile – e nemmeno realistico – tentare di riassumere e spiegare in poche pagine “idee inconciliabili con una mente comune”, come direbbe Mach; e il tentativo di Panek non può che dare alcune, poche suggestioni che lasciano solo intravvedere il significato delle teorie di Einstein e dell’intera costruzione teorica della fisica che da questa ha avuto origine. L’attuale comprensione dell’universo, conclude Panek, non è un mito della creazione, una raccolta di fantasticherie. E’ invece una raccolta di evidenze sperimentali ancora incomplete: un’equazione con una x che continuiamo a tentare di risolvere, generazione dopo generazione, per dare un senso e uno scopo a noi stessi e al mondo in cui viviamo.

ENGLISH

Readers are warned: you will not be able - warns Richard Panek in the introduction to The Mystery Under Our Feet - to know what gravity is. And it does it with a sort of pun. "I will talk about what gravity causes, and what causes gravity", because "nobody knows what gravity is, and almost nobody knows that nobody knows what gravity is. Scientists are no exception. They know that nobody knows what gravity is, because they know that they themselves don't know what gravity is. "

Gravity has never only concerned physics but has always had its roots in metaphysics and philosophy, so much so that it has been present in the most ancient myths of creation that tell how, for some fault, humans were thrown down here, by a privileged condition for which they were somewhere else, up there. In the story of the various religions, in the philosophical texts, in the ancient scientific conceptions of the corruptible world compared to the celestial spheres, crystalline and pure, cosmological explanations are sought of what can be seen moving on Earth and of what is seen moving in the skies. But you need to know how to look, so as to give rise to new problems and find possible solutions.

Galileo and the experiments with the inclined plane

Panek finds three fundamental turning points in the history of thought, and in particular in the intuitions of Galilei, Newton and Einstein. The three scientists, each in their own time, know how to look at things in an unconventional way and, reinterpreting facts considered obvious, open new perspectives for the development of knowledge. Galileo, with his experiments on the inclined plane, looks for the mathematics that exactly describes the motions and discovers that a sphere always gains speed during the fall and that, above all, accelerates constantly. Furthermore, the matter at rest remains at rest until it is set in motion, and the matter in motion remains in motion until it is stopped. But from the point of view of a sphere that rolls on a plane without friction at constant speed, Galileo thinks, there is no difference between being in motion and not being in motion.

Newton and the orbits of the celestial bodies

Newton, who gradually builds a mathematics suitable for his interpretations, uses the terms gravity and levity to indicate the tendency to go downward (when a stone falls) and upward (when a flame rises) and imagine that the gravity is caused by a "gummy", "greasy", "ductile and tenacious nature". But above all, explains Panek, Newton wonders what "being in motion" means: why should a planet not continue its motion in a straight line? Why should it deviate, curve, leave the straight path to undertake an elliptical one? In addition to the one in a straight line there must be another movement, the downward movement studied by Galileo.

By combining forward, inertial, and downward, centripetal motion, Newton manages to explain the movement of the planets along their elliptical orbits and that of the Moon around the Earth. The Moon falls to Earth. But the Earth falls towards the Moon, even if it falls at the same time towards the Sun, and the Sun falls towards the Earth, and Jupiter towards the Earth, towards the Sun and towards the Moon, and in turn they also fall towards Jupiter ... and so on: all celestial bodies travel on their straight lines as they fall towards each other. The term gravitation indicates, for Newton, the combination of the two effects, the inertial one and the centripetal one - the global effect that we perceive in the form of elliptical orbits and falling objects. But the cause remains mysterious. "I have not yet been able to deduce the reasons for these properties of gravity from the phenomena, and I do not invent hypotheses," writes Newton, but adds: "It is enough that gravity really exists and acts according to the laws we have presented." There is no need to know what it is.

The search for root causes

The centuries pass and scientific thought explores other directions: the pendulums that oscillate more slowly near the Equator give indications on the shape of the Earth, it is predicted how much the motion of a comet - that of Halley - can be influenced by Saturn and Jupiter as it moves away from the Sun, it turns out that the heart pumps blood into the body in a circular way, Lyell tries to explain "the past changes of the earth's surface with reference to the causes now underway", Darwin publishes "The origin of the species". Nature follows laws, and these laws are universal.

The "prime causes" of phenomena in religion or mathematics are sought, but certain explanations remain incomprehensible. Already in the early 1900s Mach distinguished between ordinary and non-ordinary incomprehensibility. The example he uses concerns the concepts of light and gravity of the seventeenth century. Newton thinks that light spreads in the form of balls, which he calls corpuscles. Huygens proposes to interpret light as a wave - a concept, Mach writes, "incomprehensible to Newton". Likewise, Newton's idea of remote action is "incomprehensible to Huygens". "But a century later - continues Mach - the notions become compatible, even for a common mind".

Einstein and gravitational waves

In the same years, Einstein begins to develop his mental experiments and known as observers in uniform relative motion can make different statements about the reality that appears to them. He knows that the speed of light is finite and that it does not change in a vacuum, but although the universe is understandable to everyone in the same way, each observation can be different relative to another. As Panek explains, Einstein wants a general theory that applies to objects in relative non-uniform motion. References to space and time don't make sense - he argues - if you don't specify what. Reasonings and hypotheses develop in his mind. As for space and time "unified" by Galileo, such as inertial motion in a straight line and centripetal downward movement "unified" by Newton, Einstein thinks that inertial mass (the one that measures the resistance of an object to change the its state of motion) and the gravitational mass (the one that measures the predisposition of an object to change its state of motion) measure the same thing.

In Newton's physics, matter is active and moving, while space is a passive container in which mysterious exchanges take place between the masses. In Einstein's physics matter is still active. But space also becomes active: it cooperates with matter to produce what we perceive as the effect of gravity. Matter curves space, space guides matter. The "feeling" of attraction is not only mutual: it is continuous in space and time. Einstein considers space almost literally as a fluid and thinks that the universe behaves like an ocean, globally and dynamically continuous. A wave can be observed here or a vortex there, but these phenomena do not exist in isolation. They emerge from their environment, and the environment emerges from them. The presence of a mass creates a curvature of space, generates waves - gravitational - perceived, precisely as gravity and capable of explaining the action at a distance, the "enormous absurdity" that Newton could not justify.

New cases of ordinary incomprehensibility

In the second half of the 1900s quantum mechanics opens up new research perspectives to physicists, and cosmology develops through suggestive theories on the origin and structure of the Universe, expanding its vision to hypothesize possible "multiverses" whose interpretations exceed even the limits of ordinary incomprehensibility. The traditional conceptualizations of the universe are modified and new multimedia representations, such as the documentary Interstellar, display knowledge by offering extraordinary images of incomprehensible objects such as black holes to a large audience. At the same time, very sensitive instruments such as the LIGO interferometer have been able to detect the passage of gravitational waves caused by the collision between two black holes in orbit around each other, and these results generate theories that represent new cases of "incomprehensibility ordinary ".

It is not easy - and not even realistic - to try to summarize and explain in a few pages "irreconcilable ideas with a common mind", as Mach would say; and Panek's attempt can only give some, few suggestions that only allow us to glimpse the meaning of Einstein's theories and the entire theoretical construction of physics that originated from it. The current understanding of the universe, Panek concludes, is not a myth of creation, a collection of reveries. Instead, it is a collection of experimental evidence that is still incomplete: an equation with an x that we continue to try to solve, generation after generation, to give meaning and purpose to ourselves and to the world in which we live.

Da:

https://www.galileonet.it/gravita-galileo-newton-einstein-ligo-onde-gravitazionali/

Commenti

Posta un commento