Why Immune Cells Extrude Webs of DNA and Protein / Perché le cellule immunitarie formano reti di DNA e proteine

Why Immune Cells Extrude Webs of DNA and Protein / Perché le cellule immunitarie formano reti di DNA e proteine

Segnalato dal Dott. Giusppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giusppe Cotellessa

Extracellular webs expelled by neutrophils trap invading pathogens, but these newly discovered structures also have ties to autoimmunity and cancer.

In the early 2000s, Arturo Zychlinsky at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin found that mammalian immune cells called neutrophils use an enzyme called neutrophil elastase (NE) to cleave bacterial virulence factors. When Zychlinsky and his colleagues delved deeper into this defense mechanism, they realized that when activated by bacteria, human neutrophils release NE in what, under the microscope, looked like a fibrous structure. This structure turned out to be a meshwork of NE, other proteins, and copious amounts of DNA. In cultured human neutrophils, the webs were able to trap the bacteria that had triggered their formation, thereby limiting infection, so Zychlinsky and colleagues dubbed them neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs.

The fact that neutrophils used their nuclear material to catch pathogens was intriguing to immunologists and cell biologists alike. The work of the Zychlinsky lab suggested that the release of NETs was an active process, and that the material wasn’t simply released by passive lysis. This has motivated a new line of research devoted to characterizing these unique structures, delineating the mechanisms that prompt their formation, and identifying their relevance in mammalian biology.

As more and more researchers join the burgeoning field, the spectrum of pathogens known to induce NET release from neutrophils has expanded from a variety of bacteria to fungi and, most recently, to viruses. However, it has also become clear that NETs can have negative consequences for the organisms that produce them—by activating autoimmune pathways or encouraging tumor cells to metastasize, for example.

Today, it is widely accepted that NETs have both a protective and a pathological impact on the host. In 2012, Mariana Kaplan, now of the National Institutes of Health, and the University of Tennessee’s Marko Radic termed NETs a “double-edged sword of immunity” and suggested that healthy organisms must tightly control their release to minimize negative consequences for the host. The details of NET regulation and function are now a very active area of research.

NET basics

Neutrophils are essential for immune defense and prevention of microbial overgrowth. They are very abundant—around 100 billion are produced in a human’s bone marrow in a single day—and they circulate in the bloodstream to quickly infiltrate tissues if the neutrophils detect a microbial threat. Belonging to a class of white blood cells called granulocytes, they are characterized by a cytoplasm packed with granules containing antimicrobial proteins. Neutrophils can engulf pathogens and then fuse their granules with their phagosomes, which contain the internalized microbes. Alternatively, the cells can fuse their granules with the plasma membrane to release antimicrobials to attack extracellular parasites.

Research on neutrophils is complicated by the fact that they are short-lived cells. For instance, unlike some other human cell types, neutrophils cannot be cultured for more than a few hours, and they are not amenable to gene editing. For this reason, we still lack a detailed mechanistic picture of how exactly NETs are formed. Early reports confirmed the original hypothesis that NETs do not result from passive necrosis of neutrophils. Later studies added complexity by demonstrating that different inflammatory triggers induce various pathways that all lead to the release of NETs, and that NET release doesn’t always result in lysis of the neutrophil.

That said, most pathways of NET formation do kill the immune cell, typically as a result of the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Bacterial or fungal pathogens cause neutrophils to activate kinases that induce assembly of an enzyme complex called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase. NADPH oxidase then produces large amounts of superoxide—a highly reactive oxygen compound that carries an extra electron—during a process called the neutrophil oxidative burst. ROS resulting from the oxidative burst trigger disintegration of a multiprotein complex to release active NE, a primary component of NETs, into the cytoplasm.

NE then migrates to the neutrophil’s nucleus, where it cleaves histones and other proteins to decondense the chromatin. Eventually, the chromatin fills up the entire cell until the cell lyses and extrudes the NET into the extracellular space, a process known as NETosis. We recently identified an important role for the pore-forming protein gasdermin D in both the nuclear expansion and the lysis processes, although the mechanisms aren’t yet clear. In the extracellular space, the webs are thought to trap and kill the triggering pathogens.

NETs in immune defense

NETs’ ability to trap microbial invaders has been demonstrated in vitro for a variety of pathogens. The structures appear to be particularly important in defense against pathogenic fungi, suggesting NETs may have evolved as a way to trap large organisms that cannot be engulfed via phagocytosis. But a lack of specific genetic tools has made it difficult to nail down the exact contribution of NETs to antimicrobial defense in vivo. Most of the molecules that have so far been found to regulate NETs are also involved in other immune responses, so a “NET knockout” organism is still beyond our reach.

In spite of these technical challenges, researchers are slowly elucidating the function of NETs in immunity. In 2012, Paul Kubes of the University of Calgary and colleagues depleted NETs in mice with skin infections by injecting recombinant DNase 1, an enzyme that chops up the DNA backbone of NETs after they are released. This led to increased dissemination of Staphylococcus aureus from the skin to the bloodstream, demonstrating that NETs participate in containing bacteria at the site of entry. This experimental strategy of NET destruction by nucleases is also used naturally by pathogenic bacteria as a way to escape from NETs: Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species both secrete DNases, and experimental deletion of the genes that encode these NET-degrading enzymes in those microbes leads to reduced bacterial virulence.

The idea that NETs form barriers at mucosal surfaces was recently strengthened by additional work from Kubes and Ajitha Thanabalasuriar, now at MedImmune, showing that NETs form an exclusionary microbicidal “dead zone” in infected corneas. This confines bacteria to the outer surface of the eye and prevents them from entering the eye and spreading to the brain.

The role of NETs in infections is not limited to trapping microbes, however. The structures contain multiple anti-microbial molecules. Histones, for example, are major components of the chromatin in NETs, and these proteins have important bactericidal and immunostimulatory functions. After discovering NETs, Zychlinsky proposed antimicrobial defense as the alternative, less-studied function of histones, whose more prominent and established function is to organize and package DNA in the nucleus.

NETs also contain several alarmins, molecules that activate the immune system and help propagate the inflammatory response. Release of alarmin-containing NETs alerts the rest of the immune system to the presence of microbes or foreign substances. Twenty-five years ago, immunologist Polly Matzinger of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases proposed the “danger theory” of immunity, postulating that the immune system is concerned with limiting virulent bacteria and tolerating nontoxic ones. NET release may serve as one mechanism of flagging intolerable bacteria. Instead of engulfing the microbes and initiating the immunologically silent apoptotic pathway, the NET-producing form of cell death utilizes proinflammatory pathways. Bacteria that are toxic enough to lead to NETosis will send a powerful inflammatory signal via the alarmins in NETs. This is illustrated nicely in the case of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen that is able to colonize the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. P. aeruginosa only triggers NETs when it expresses virulence factors such as flagella or the toxin pyocyanin. In the absence of these virulence factors, neutrophils mostly respond to these bacteria by attempting to engulf them.

Triggers of NET formation

It’s not just pathogens that can initiate NET formation. A variety of host molecules can also activate neutrophils to extrude their innards into the extracellular space. One example is crystals of cholesterol, a form of the lipid that causes inflammation. And in 2017, we and our colleagues found that mitogenic signaling, which induces cell division in some immune cells, also triggers various cell cycle–related phenomena in neutrophils, but with the consequence of NET formation rather than division.

Notably, NETs can form independently of the canonical pathway involving ROS-producing NADPH oxidase, stimulated by pathogens or compounds such as ionophores, agents that lead to ion fluxes through the cell membrane. It is unclear whether NADPH oxidase–independent pathways rely on ROS produced by other means or whether these are truly ROS-independent processes. Interestingly, ionophore-driven activation of neutrophils triggers strong calcium fluxes, which activate the enzyme peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4). PAD4 converts the amino acid arginine to citrulline and acts on various substrates, including histones. Citrullination of histones is thus a good biomarker for NETs in the extracellular space.

Perhaps the most surprising mechanism of NET formation involves DNA release by living neutrophils, a process termed vital NETosis by Kubes and colleagues. It is unclear which molecules mediate DNA release in this case—or how the release even occurs—but it seems that neutrophils remain viable, phagocytic, and are even able to “push” the NET forward as they migrate. These findings demonstrate that neutrophils do not necessarily die after they form NETs.

Downsides of NETs

Unfortunately, as with other neutrophil responses, NETs have a dark side that makes them dangerous when inappropriately deployed. This is the case with malaria, which is caused by Plasmodium parasites that invade and proliferate in red blood cells. Infected cells adhere to the walls of blood vessels throughout the body, leading to pathological changes such as obstruction of capillaries and inflammation. Our group made the surprising discovery that NETs cause blood vessels to become sticky by expressing cytoadhesive proteins, which facilitate binding by Plasmodium-infected cells. In the absence of NETs, infected mice tolerated the presence of parasites and showed no signs of disease.

Similarly harmful effects of NETs have been described in noninfectious diseases such as lupus, an autoimmune condition. In these instances, NET release is dysregulated, triggering chronic pathological inflammation, with NETs potentially acting as a source of autoantigens and immunostimulatory molecules.

As large, fibrous extracellular structures, NETs are also excellent scaffolds for thrombosis, the formation of blood clots that are the main cause of heart attack and stroke. Denisa Wagner’s group at Harvard Medical School has shown that NETs are found in both arterial and deep vein thrombosis and that their degradation by DNase 1 is protective in animal models of the disease. Before being linked to NETs, histone-packaged bits of DNA called nucleosomes were known to have procoagulant properties.

NETs can also be subverted by malignant cells to facilitate metastasis. The link between inflammation and cancer progression has long been established, but it was a seminal study by the laboratory of Mikala Egeblad at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory that demonstrated NETs can reawaken dormant tumor cells. Working in mouse models of breast and prostate cancer, the Egeblad lab showed that bacterial antigen–triggered NETs remodel the microenvironment to encourage activation and proliferation of tumor cells. Importantly, researchers were able to block metastasis by either interfering with NET production or by blocking downstream signaling effects. Inhibition of NETs is thus a potential strategy for developing novel cancer therapies, and is likely to be the focus of intense research in coming years.

Open questions

Despite very active research, there are still a number of unknowns concerning NETs. Mechanistically, we do not fully understand how many pathways exist to induce neutrophils to make NETs, or how these pathways might interact. And the pathological effects of NETs are only beginning to be detailed, while their potential healing properties are currently understudied.

Another important question is what determines whether a neutrophil undergoes lytic or non-lytic NET formation. The concept of neutrophils releasing NETs while remaining motile and capable of engulfing bacteria is intriguing, but more studies are required to elucidate when and where this occurs.

Finally, an interesting and unsolved question is how evolutionarily conserved the process of NET formation is. Plant root cells release chromatin to defend against pathogens, and a recent study described NET-like structures released from phagocytes of invertebrates, such as crabs, mussels, and anemones. The process of cells releasing their DNA as a protective mechanism might therefore be ancient. Further studies will hopefully identify the origin of NETs, and thereby shed light on this fascinating and important process.

NET Formation

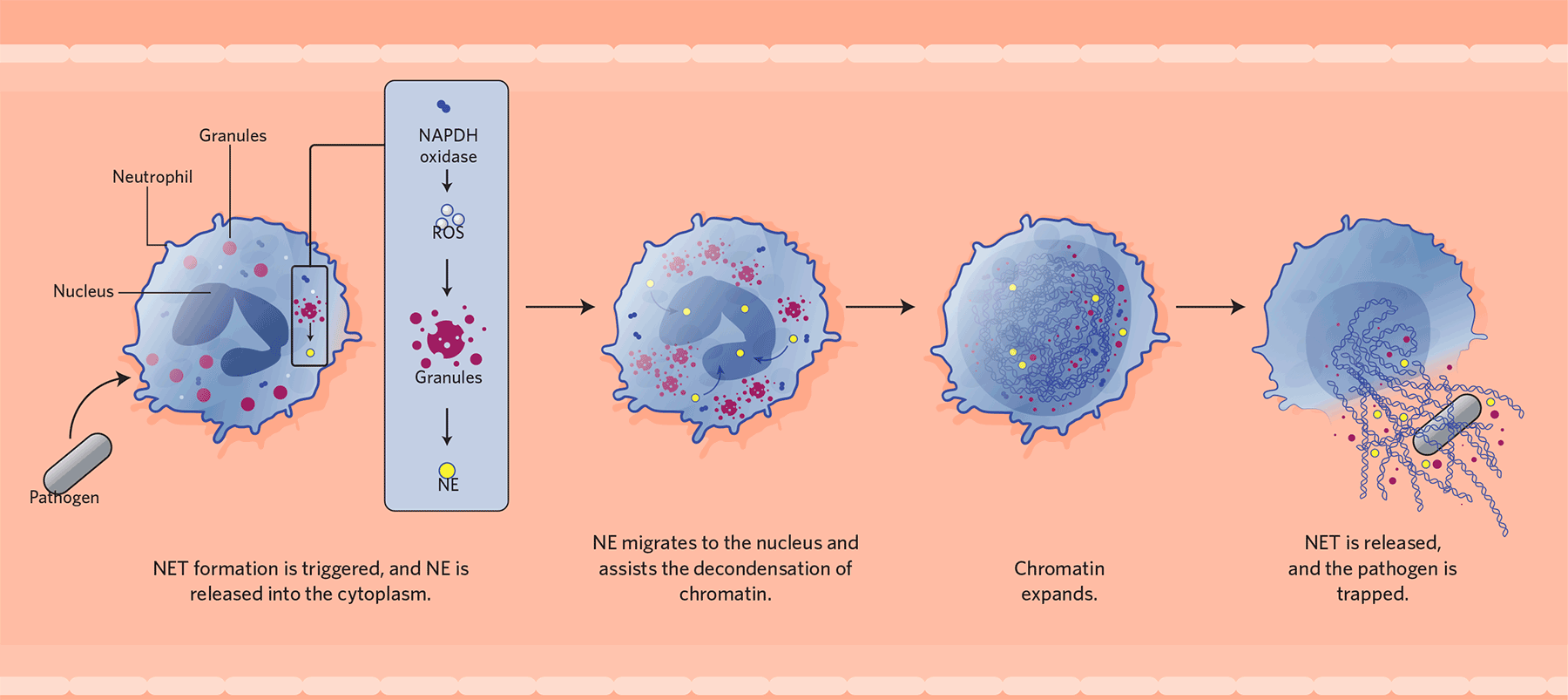

When a neutrophil encounters a pathogen, it can respond in

several ways: phagocytosis, degranulation, or by releasing neutrophil

extracellular traps (NETs). In NET release, shown here, the enzyme complex

NADPH oxidase generates reactive oxide species (ROS), which in turn initiate

the disintegration of granules, releasing neutrophil elastase (NE). NE then

migrates to the neutrophil’s nucleus, where it cleaves proteins that package

the cell’s DNA as chromosomes. The chromatin expands until it fills up the

entire cell, which breaks open and extrudes the NET into the extracellular

space. There, the webs are thought to trap and kill the triggering pathogens.

Trapping / Intrappolamento

Barriers / Barriere

Immune signaling / Segnalazione per il sistema immunitario

NET components act as alarm signals to activate additional immune cells and propagate the inflammatory response. Macrophages and dendritic cells sense various components of the NETs, including DNA and proteins, which leads them to produce proinflammatory mediators. / I componenti .NET agiscono come segnali di allarme per attivare ulteriori cellule immunitarie e propagare la risposta infiammatoria. I macrofagi e le cellule dendritiche rilevano vari componenti dei NET, tra cui DNA e proteine, che li portano a produrre mediatori proinfiammatori.

Countering inflammation / Contrastare l'infiammazione

When present at high density, NETs can cleave proinflammatory cytokines and help resolve inflammation. / Quando sono presenti ad alta densità, i NET possono scindere le citochine proinfiammatorie e aiutare a risolvere l'infiammazione.

AND DISEASE / MALATTIA

NETs have a dark side that makes them dangerous when inappropriately deployed. The structures have been implicated as contributors to a range of conditions. / I NET hanno un lato oscuro che li rende pericolosi se utilizzati in modo inappropriato. Le strutture sono state implicate come contributori a una serie di condizioni.

1 CancerNET-associated proteins lead to reawakening of dormant cancer cells and convert them to proliferating metastatic cells. / Le proteine associate a NET portano al risveglio delle cellule tumorali dormienti e le convertono in cellule metastatiche proliferanti | |

2 | Malaria / MalariaNET formation is triggered during malaria, and then the structures are cleaved into fragments by circulating DNase1. These fragments lead to upregulation of cytoadhesion receptors on the surface of endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. Cells infected with Plasmodium parasites bind to these receptors, which helps them avoid the immune response in the spleen and causes damaging inflammation. / La formazione di NET viene innescata durante la malaria e quindi le strutture vengono tagliate in frammenti facendo circolare DNasi1. Questi frammenti portano alla sovraregolazione dei recettori di citoadesione sulla superficie delle cellule endoteliali che rivestono i vasi sanguigni. Le cellule infettate dai parassiti del Plasmodium si legano a questi recettori, il che le aiuta a evitare la risposta immunitaria nella milza e provoca infiammazioni dannose. |

3 | Thrombosis / TrombosiNET components promote blood coagulation and obstruction of small blood vessels. / I componenti NET promuovono la coagulazione del sangue e l'ostruzione dei piccoli vasi sanguigni. |

4 | Atherosclerosis / AterosclerosiNETs activate macrophages, inducing them to produce proinflammatory cytokines. The histones associated with NETs also damage the smooth muscle of the arterial walls. / I NET attivano i macrofagi, inducendoli a produrre citochine proinfiammatorie. Gli istoni associati ai NET danneggiano anche la muscolatura liscia delle pareti arteriose. |

5 | Lupus / LupusThis autoimmune disease is characterized by production of autoantibodies directed against one’s own DNA. NETs are thought to be a source of autoantigens, as well as immunostimulatory molecules that activate dendritic cells and fuel inflammation. / Questa malattia autoimmune è caratterizzata dalla produzione di autoanticorpi diretti contro il proprio DNA. Si pensa che i NET siano una fonte di autoantigeni, nonché di molecole immunostimolanti che attivano le cellule dendritiche e alimentano l'infiammazione. |

ITALIANO

Le reti extracellulari espulse dai neutrofili intrappolano gli agenti patogeni invasori, ma queste strutture scoperte di recente hanno anche legami con l'autoimmunità e il cancro.

All'inizio degli anni 2000, Arturo Zychlinsky del Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology di Berlino ha scoperto che le cellule immunitarie dei mammiferi chiamate neutrofili utilizzano un enzima chiamato elastasi neutrofila (NE) per scindere i fattori di virulenza batterica. Quando Zychlinsky ed i suoi colleghi hanno approfondito questo meccanismo di difesa, si sono resi conto che quando attivati dai batteri, i neutrofili umani rilasciano NE in quella che, al microscopio, sembrava una struttura fibrosa. Questa struttura si è rivelata un reticolo di NE, altre proteine e abbondanti quantità di DNA. Nei neutrofili umani coltivati, le reti sono state in grado di intrappolare i batteri che avevano innescato la loro formazione, limitando così l'infezione, quindi Zychlinsky e colleghi le hanno soprannominate trappole extracellulari neutrofili o NET.

Il fatto che i neutrofili usassero il loro materiale nucleare per catturare gli agenti patogeni era intrigante sia per gli immunologi che per i biologi cellulari. Il lavoro del laboratorio Zychlinsky ha suggerito che il rilascio di NET fosse un processo attivo e che il materiale non fosse semplicemente rilasciato mediante lisi passiva. Ciò ha motivato una nuova linea di ricerca dedicata alla caratterizzazione di queste strutture uniche, delineando i meccanismi che stimolano la loro formazione e identificando la loro rilevanza nella biologia dei mammiferi.

Man mano che sempre più ricercatori si uniscono al campo in espansione, lo spettro di agenti patogeni noti per indurre il rilascio di NET dai neutrofili si è espanso da una varietà di batteri a funghi e, più recentemente, a virus. Tuttavia, è anche diventato chiaro che i NET possono avere conseguenze negative per gli organismi che li producono, attivando percorsi autoimmuni o incoraggiando le cellule tumorali a metastatizzare, per esempio.

Oggi, è ampiamente accettato che i NET abbiano un impatto sia protettivo che patologico sull'ospite. Nel 2012, Mariana Kaplan, ora del National Institutes of Health, e Marko Radic dell'Università del Tennessee, hanno definito NET una "spada a doppio taglio dell'immunità" e hanno suggerito che gli organismi sani devono controllare strettamente il loro rilascio per ridurre al minimo le conseguenze negative per l'ospite. I dettagli della regolamentazione e della funzione NET sono ora un'area di ricerca molto attiva.

Nozioni di base su NET

I neutrofili sono essenziali per la difesa immunitaria e la prevenzione della proliferazione microbica. Sono molto abbondanti - circa 100 miliardi vengono prodotti nel midollo osseo di un essere umano in un solo giorno - e circolano nel flusso sanguigno per infiltrarsi rapidamente nei tessuti se i neutrofili rilevano una minaccia microbica. Appartenenti a una classe di globuli bianchi chiamati granulociti, sono caratterizzati da un citoplasma ricco di granuli contenenti proteine antimicrobiche. I neutrofili possono inghiottire gli agenti patogeni e quindi fondere i loro granuli con i loro fagosomi, che contengono i microbi interiorizzati. In alternativa, le cellule possono fondere i loro granuli con la membrana plasmatica per rilasciare antimicrobici per attaccare i parassiti extracellulari.

La ricerca sui neutrofili è complicata dal fatto che sono cellule a vita breve. Ad esempio, a differenza di altri tipi di cellule umane, i neutrofili non possono essere coltivati per più di poche ore e non sono suscettibili di editing genetico. Per questo motivo, ci manca ancora un quadro meccanicistico dettagliato di come si formano esattamente i NET. I primi rapporti hanno confermato l'ipotesi originale che i NET non derivano dalla necrosi passiva dei neutrofili. Studi successivi hanno aggiunto complessità dimostrando che diversi trigger infiammatori inducono vari percorsi che portano tutti al rilascio di NET, e che il rilascio di NET non sempre provoca la lisi dei neutrofili.

Detto questo, la maggior parte dei percorsi di formazione NET uccide la cellula immunitaria, tipicamente come risultato della produzione di specie reattive dell'ossigeno (ROS). Patogeni batterici o fungini inducono i neutrofili ad attivare chinasi che inducono l'assemblaggio di un complesso enzimatico chiamato nicotinamide adenina dinucleotide fosfato (NADPH) ossidasi. La NADPH ossidasi produce quindi grandi quantità di superossido, un composto dell'ossigeno altamente reattivo che trasporta un elettrone in più, durante un processo chiamato burst ossidativo dei neutrofili. I ROS risultanti dal burst ossidativo innescano la disintegrazione di un complesso multiproteico per rilasciare NE attivo, un componente primario dei NET, nel citoplasma.

NE poi migra verso il nucleo dei neutrofili, dove scinde gli istoni e altre proteine per decondensare la cromatina. Alla fine, la cromatina riempie l'intera cellula fino a quando la cellula non lisi ed estrude il NET nello spazio extracellulare, un processo noto come NETosis. Recentemente abbiamo identificato un ruolo importante per la proteina gasdermin D che forma i pori sia nell'espansione nucleare che nei processi di lisi, sebbene i meccanismi non siano ancora chiari. Nello spazio extracellulare, si pensa che le ragnatele intrappolino e uccidano i patogeni scatenanti.

NET in difesa immunitaria

La capacità di NET di intrappolare gli invasori microbici è stata dimostrata in vitro per una varietà di patogeni. Le strutture sembrano essere particolarmente importanti nella difesa contro i funghi patogeni, suggerendo che i NET potrebbero essersi evoluti come un modo per intrappolare grandi organismi che non possono essere inghiottiti tramite la fagocitosi. Ma la mancanza di strumenti genetici specifici ha reso difficile definire il contributo esatto dei NET alla difesa antimicrobica in vivo. La maggior parte delle molecole che finora si è scoperto che regolano i NET sono coinvolte anche in altre risposte immunitarie, quindi un organismo "NET knockout" è ancora fuori dalla nostra portata.

Nonostante queste sfide tecniche, i ricercatori stanno lentamente chiarendo la funzione dei NET nell'immunità. Nel 2012, Paul Kubes dell'Università di Calgary e colleghi hanno impoverito i NET nei topi con infezioni della pelle iniettando DNasi 1 ricombinante, un enzima che sminuzza la spina dorsale del DNA dei NET dopo che sono stati rilasciati. Ciò ha portato a una maggiore diffusione di Staphylococcus aureus dalla pelle al flusso sanguigno, dimostrando che i NET partecipano al contenimento dei batteri nel sito di ingresso. Questa strategia sperimentale di distruzione del NET da parte delle nucleasi viene anche utilizzata naturalmente dai batteri patogeni come un modo per sfuggire ai NET: le specie Staphylococcus e Streptococcus secernono entrambe DNasi e la delezione sperimentale dei geni che codificano questi enzimi di degradazione del NET in quei microbi porta a una riduzione virulenza batterica.

L'idea che le RETI formino barriere alle superfici delle mucose è stata recentemente rafforzata da un lavoro aggiuntivo di Kubes e Ajitha Thanabalasuriar, ora a MedImmune, dimostrando che le RETI formano una "zona morta" microbicida di esclusione nelle cornee infette. Questo confina i batteri alla superficie esterna dell'occhio e impedisce loro di entrare nell'occhio e di diffondersi al cervello.

Il ruolo dei NET nelle infezioni, tuttavia, non si limita a intrappolare i microbi. Le strutture contengono più molecole antimicrobiche. Gli istoni, ad esempio, sono i principali componenti della cromatina nei NET e queste proteine hanno importanti funzioni battericide e immunostimolatorie. Dopo aver scoperto i NET, Zychlinsky ha proposto la difesa antimicrobica come funzione alternativa e meno studiata degli istoni, la cui funzione più importante e consolidata è quella di organizzare e impacchettare il DNA nel nucleo.

I NET contengono anche diverse allarmine, molecole che attivano il sistema immunitario e aiutano a propagare la risposta infiammatoria. Il rilascio di reti contenenti allarmina avverte il resto del sistema immunitario della presenza di microbi o sostanze estranee. Venticinque anni fa, l'immunologa Polly Matzinger del National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases propose la "teoria del pericolo" dell'immunità, postulando che il sistema immunitario si preoccupa di limitare i batteri virulenti e tollerare quelli non tossici. Il rilascio netto può servire come un meccanismo per segnalare i batteri intollerabili. Invece di inghiottire i microbi e avviare il percorso apoptotico immunologicamente silenzioso, la forma di morte cellulare che produce NET utilizza percorsi proinfiammatori. I batteri che sono abbastanza tossici da portare a NETosis invieranno un potente segnale infiammatorio tramite le allarmine in NET. Ciò è ben illustrato nel caso di Pseudomonas aeruginosa, un patogeno opportunista in grado di colonizzare i polmoni dei pazienti con fibrosi cistica. P. aeruginosa innesca NET solo quando esprime fattori di virulenza come flagelli o la tossina piocianina. In assenza di questi fattori di virulenza, i neutrofili rispondono principalmente a questi batteri tentando di inghiottirli.

Trigger della formazione NET

Non sono solo gli agenti patogeni che possono avviare la formazione di NET. Una varietà di molecole ospiti può anche attivare i neutrofili per formare la loro struttura nello spazio extracellulare. Un esempio sono i cristalli di colesterolo, una forma del lipide che causa l'infiammazione. E nel 2017, noi ed i nostri colleghi abbiamo scoperto che la segnalazione mitogenica, che induce la divisione cellulare in alcune cellule immunitarie, innesca anche vari fenomeni legati al ciclo cellulare nei neutrofili, ma con la conseguenza della formazione di NET piuttosto che della divisione.

In particolare, i NET possono formarsi indipendentemente dal percorso canonico che coinvolge la NADPH ossidasi che produce ROS, stimolata da agenti patogeni o composti come ionofori, agenti che portano a flussi ionici attraverso la membrana cellulare. Non è chiaro se i percorsi indipendenti dalla NADPH ossidasi si basino su ROS prodotti con altri mezzi o se questi siano processi veramente indipendenti dai ROS. È interessante notare che l'attivazione dei neutrofili guidata dagli ionofori innesca forti flussi di calcio, che attivano l'enzima peptidil arginina deiminasi 4 (PAD4). PAD4 converte l'aminoacido arginina in citrullina e agisce su vari substrati, inclusi gli istoni. La citrullinazione degli istoni è quindi un buon biomarcatore per i NET nello spazio extracellulare.

Forse il meccanismo più sorprendente della formazione di NET coinvolge il rilascio di DNA da parte dei neutrofili viventi, un processo chiamato NETosis vitale da Kubes e colleghi. Non è chiaro quali molecole mediano il rilascio di DNA in questo caso - o come si verifica il rilascio - ma sembra che i neutrofili rimangano vitali, fagocitici e siano persino in grado di "spingere" in avanti il NET durante la migrazione. Questi risultati dimostrano che i neutrofili non muoiono necessariamente dopo aver formato NET.

Aspetti negativi di NET

Sfortunatamente, come con altre risposte dei neutrofili, le reti hanno un lato oscuro che le rende pericolose se utilizzate in modo inappropriato. Questo è il caso della malaria, che è causata dai parassiti Plasmodium che invadono e proliferano nei globuli rossi. Le cellule infette aderiscono alle pareti dei vasi sanguigni in tutto il corpo, portando a cambiamenti patologici come l'ostruzione dei capillari e l'infiammazione. Il nostro gruppo ha fatto la sorprendente scoperta che i NET fanno sì che i vasi sanguigni diventino appiccicosi esprimendo proteine citoadesive, che facilitano il legame da parte delle cellule infettate da Plasmodium. In assenza di NET, i topi infetti hanno tollerato la presenza di parassiti e non hanno mostrato segni di malattia.

Allo stesso modo, effetti dannosi dei NET sono stati descritti in malattie non infettive come il lupus, una condizione autoimmune. In questi casi, il rilascio di NET è disregolato, innescando un'infiammazione patologica cronica, con i NET che potenzialmente agiscono come fonte di autoantigeni e molecole immunostimolatrici.

In quanto strutture extracellulari grandi e fibrose, le reti sono anche eccellenti strutture per la trombosi, la formazione di coaguli di sangue che sono la principale causa di infarto e ictus. Il gruppo di Denisa Wagner presso la Harvard Medical School ha dimostrato che i NET si trovano nella trombosi venosa sia arteriosa che profonda e che la loro degradazione da parte della DNasi 1 è protettiva nei modelli animali della malattia. Prima di essere collegati ai NET, i componenti di DNA confezionati con istoni chiamati nucleosomi erano noti per avere proprietà procoagulanti.

I NET possono anche essere sovvertiti da cellule maligne per facilitare le metastasi. Il legame tra infiammazione e progressione del cancro è stato stabilito da tempo, ma è stato uno studio fondamentale del laboratorio di Mikala Egeblad al Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory che ha dimostrato che i NET possono risvegliare le cellule tumorali dormienti. Lavorando su modelli murini di cancro al seno e alla prostata, il laboratorio Egeblad ha dimostrato che i NET attivati da antigeni batterici rimodellano il microambiente per incoraggiare l'attivazione e la proliferazione delle cellule tumorali. È importante sottolineare che i ricercatori sono stati in grado di bloccare le metastasi interferendo con la produzione di NET o bloccando gli effetti di segnalazione a valle. L'inibizione dei NET è quindi una potenziale strategia per lo sviluppo di nuove terapie antitumorali ed è probabile che sarà al centro di intense ricerche nei prossimi anni.

Domande aperte

Nonostante la ricerca molto attiva, ci sono ancora una serie di incognite riguardanti i NET. Meccanicamente, non comprendiamo appieno quanti percorsi esistono per indurre i neutrofili a creare NET, o come questi percorsi potrebbero interagire. E gli effetti patologici dei NET stanno appena iniziando a essere dettagliati, mentre le loro potenziali proprietà curative sono attualmente sottovalutate.

Un'altra domanda importante è cosa determina se un neutrofilo va incontro a formazione di NET litico o non litico. Il concetto di neutrofili che rilasciano NET pur rimanendo mobili e capaci di inghiottire i batteri è intrigante, ma sono necessari ulteriori studi per chiarire quando e dove ciò si verifica.

Infine, una domanda interessante e irrisolta è quanto sia evolutivamente conservato il processo di formazione della NET. Le cellule delle radici delle piante rilasciano cromatina per difendersi dagli agenti patogeni e un recente studio ha descritto strutture simili a RETE rilasciate dai fagociti di invertebrati, come granchi, cozze e anemoni. Il processo delle cellule che rilasciano il loro DNA come meccanismo protettivo potrebbe quindi essere antico. Si spera che ulteriori studi identificheranno l'origine dei NET e quindi faranno luce su questo processo affascinante e importante.

Formazione di NET

Quando un neutrofilo incontra un patogeno, può rispondere in diversi modi: fagocitosi, degranulazione o rilasciando trappole extracellulari dei neutrofili (NET). Nel rilascio NET, mostrato qui, il complesso enzimatico NADPH ossidasi genera specie di ossido reattivo (ROS), che a loro volta iniziano la disintegrazione dei granuli, rilasciando l'elastasi neutrofila (NE). NE poi migra verso il nucleo dei neutrofili, dove scinde le proteine che impacchettano il DNA della cellula come cromosomi. La cromatina si espande fino a riempire l'intera cellula, che si apre ed espelle il NET nello spazio extracellulare. Lì, si pensa che le reti intrappolino e uccidano i patogeni scatenanti.

Da:

https://www.the-scientist.com/features/why-immune-cells-extrude-webs-of-dna-and-protein-66459

Joy and happiness is all i see around ever since i came in contact with this great man. i complained bitterly to him about me having herpes only for him to tell me it’s a minor stuff. He told me he has cured thousands of people but i did not believe until he sent me the herbal medicine and i took it as instructed by this great man, only to go to the hospital after two weeks for another test and i was confirmed negative. For the first time in four years i was getting that result. i want to use this medium to thank this great man. His name is Dr aziegbe, i came in contact with his email through a friend in UK and ever since then my live has been full with laughter and great peace of mind. i urge you all with herpes or HSV to contact him if you willing to give him a chance. you can contact him through this email DRAZIEGBE1SPELLHOME@GMAIL .COM or you can also WhatsApp him +2349035465208

RispondiEliminaHe also cured my friend with HIV and ever since then i strongly believe he can do all things. Don't be deceived thinking he does not work, i believe if you can get in contact with this man all your troubles will be over. i have done my part in spreading the good news. Contact him through his email and you will be the next to testify of his great work.