‘HOT’ CRISPR Tool Creates Fast and Efficient Knock-Ins / Lo strumento CRISPR "CALDO" crea inserimenti rapidi ed efficienti

‘HOT’ CRISPR Tool Creates Fast and Efficient Knock-Ins / Lo strumento CRISPR "CALDO" crea inserimenti rapidi ed efficienti

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

The potential that gene-editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 hold for eliminating disease and genetic disorders is immense. The ability to excise a mutant gene and replace it with an unaltered version may become the gold standard by which physicians treat patients in the near future. Leading up to these potential new therapies, scientists continue to utilize tools that recapitulate human tissues and body systems as accurately as possible. These mini-organs or organoids have been a major advance for researchers studying various diseases such as cancer. Now, investigators at the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht have developed a new genetic tool to label specific genes in human organoids.

The novel method, called CRISPR-HOT, was utilized to investigate how hepatocytes divide and how abnormal cells with too much DNA appear. The researchers showed that by disabling the cancer gene TP53, unstructured divisions of abnormal hepatocytes were more frequent, which may contribute to cancer development. Findings from the new study were published recently in Nature Cell Biology through an article titled “Fast and efficient generation of knock-in human organoids using homology-independent CRISPR–Cas9 precision genome editing.”

Organoids grow from a very small piece of tissue, and researchers have been able to do this for a vast array of organs. The ability to genetically alter these organoids would help a great deal in studying biological processes and modeling diseases. So far, however, the generation of genetically altered human organoids has been proven difficult due to the lack of easy genome engineering methods.

“CRISPR–Cas9 technology has revolutionized genome editing and is applicable to the organoid field. However, precise integration of exogenous DNA sequences into human organoids is lacking robust knock-in approaches,” the authors wrote.

A few years ago, researchers discovered that CRISPR-Cas9, which acts like tiny molecular scissors, can precisely cut at a specific place in the DNA. This new technology greatly helped and simplified genetic engineering.

“The little wound in the DNA can activate two different mechanisms of repair in the cells, that can both be used by researchers to coerce the cells to take up a new part of DNA, at the place of the wound,” remarked study author Delilah Hendriks, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Hubrecht Institute.

One method, called non-homologous end joining, was thought to make frequent mistakes and therefore until now not often used to insert new pieces of DNA. “Since some earlier work in mice indicated that new pieces of DNA can be inserted via non-homologous end joining, we set out to test this in human organoids,” noted lead study investigator Benedetta Artegiani, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Hubrecht Institute.

The research team then discovered that inserting whatever piece of DNA into human organoids through non-homologous end joining is actually more efficient and robust than the other method that has been used until now. They named their new method CRISPR-HOT.

“CRISPR–Cas9-mediated homology-independent organoid transgenesis (CRISPR–HOT), enables efficient generation of knock-in human organoids representing different tissues,” the authors explained. “CRISPR–HOT avoids extensive cloning and outperforms homology-directed repair (HDR) in achieving precise integration of exogenous DNA sequences into desired loci, without the necessity to inactivate TP53 in untransformed cells, which was previously used to increase HDR-mediated knock-in. CRISPR–HOT was used to fluorescently tag and visualize subcellular structural molecules and to generate reporter lines for rare intestinal cell types. A double reporter—in which the mitotic spindle was labeled by endogenously tagged tubulin and the cell membrane by endogenously tagged E-cadherin—uncovered modes of human hepatocyte division.”

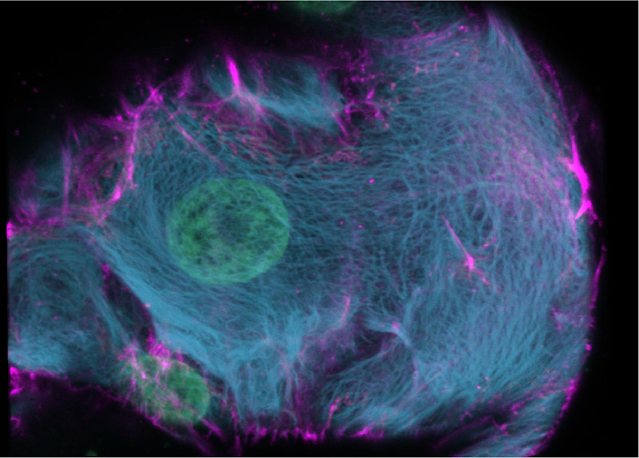

Cell division in 3D organoids shows that healthy (left) organoids show organized division (arrow), while organoids in which the cancer gene TP53 is disabled (right) show chaotic cell divisions (arrows). / La divisione cellulare negli organoidi 3D mostra che gli organoidi sani (a sinistra) mostrano una divisione organizzata (freccia), mentre gli organoidi in cui il gene del cancro TP53 è disabilitato (a destra) mostrano divisioni cellulari caotiche (frecce). [Benedetta Artegiani, Delilah Hendriks, ©Hubrecht Institute]

The Hubrecht scientists then used CRISPR-HOT to insert fluorescent labels into the DNA of human organoids, in such a way that these fluorescent labels were attached to specific genes they wanted to study. First, the researchers marked specific types of cells that are very rare in the intestine: the enteroendocrine cells. These cells produce hormones to regulate, for example, glucose levels, food intake, and stomach emptying. Because these cells are so rare, they are difficult to study. However, with CRISPR-HOT, the researchers easily “painted” these cells in different colors, after which they easily identified and analyzed them.

Next, the researchers painted organoids derived from a specific cell type in the liver, the biliary ductal cells. Using CRISPR-HOT they visualized keratins, proteins involved in the skeleton of cells. Now that they could look at these keratins in detail and at high resolution, the researchers uncovered their organization in an ultra-structural way. These keratins also change expression when cells specialize or differentiate. Therefore, the researchers anticipate that CRISPR-HOT may be useful to study cell fate and differentiation.

Within the liver, there are many hepatocytes that contain two (or even more) times the DNA of a normal cell. It is unclear how these cells are formed and whether they are able to divide because of this abnormal quantity of DNA. Older adults contain more of these abnormal hepatocytes, but it is unclear if they are related to diseases such as cancer. Artegiani and Hendriks used CRISPR-HOT to label specific components of the cell division machinery in hepatocyte organoids and studied the process of cell division.

“We saw that ‘normal’ hepatocytes divide very orderly, always splitting into two daughter cells in a certain direction,” Artegiani explained.

Hendriks added that “we also found several divisions in which an abnormal hepatocyte was formed. For the first time, we saw how a ‘normal’ hepatocyte turns into an abnormal one.”

In addition to these findings, the researchers studied the effects of a mutation often found in liver cancer, in the gene TP53, on abnormal cell division in hepatocytes. Without TP53 these abnormal hepatocytes were dividing much more often. This may be one of the ways that TP53 contributes to cancer development. The researchers believe that CRISPR-HOT can be applied to many types of human organoids, to visualize any gene or cell type, and to study many developmental and disease-related questions.

ITALIANO

Il potenziale che gli strumenti di modifica genetica come CRISPR-Cas9 hanno per eliminare malattie e disturbi genetici è immenso. La capacità di asportare un gene mutante e sostituirlo con una versione inalterata potrebbe diventare il gold standard con cui i medici curano i pazienti nel prossimo futuro. In vista di queste potenziali nuove terapie, gli scienziati continuano a utilizzare strumenti che ricapitolano i tessuti umani ed i sistemi del corpo nel modo più accurato possibile. Questi mini-organi o organoidi hanno rappresentato un importante progresso per i ricercatori che studiano varie malattie come il cancro. Ora, i ricercatori dell'Istituto Hubrecht di Utrecht hanno sviluppato un nuovo strumento genetico per etichettare geni specifici negli organoidi umani.

Il nuovo metodo, chiamato CRISPR-HOT, è stato utilizzato per studiare come si dividono gli epatociti e come appaiono cellule anormali con troppo DNA. I ricercatori hanno dimostrato che disabilitando il gene del cancro TP53, le divisioni non strutturate di epatociti anormali erano più frequenti, il che può contribuire allo sviluppo del cancro. I risultati del nuovo studio sono stati pubblicati di recente su Nature Cell Biology attraverso un articolo intitolato "Generazione rapida ed efficiente di organoidi umani knock-in utilizzando l'editing genomico di precisione CRISPR-Cas9 indipendente dall'omologia".

Gli organoidi crescono da un pezzo di tessuto molto piccolo ed i ricercatori sono stati in grado di farlo per una vasta gamma di organi. La capacità di alterare geneticamente questi organoidi aiuterebbe molto nello studio dei processi biologici e nella modellizzazione delle malattie. Finora, tuttavia, la generazione di organoidi umani geneticamente modificati si è dimostrata difficile a causa della mancanza di metodi di ingegneria genomica facili.

“La tecnologia CRISPR – Cas9 ha rivoluzionato l'editing del genoma ed è applicabile al campo degli organoidi. Tuttavia, l'integrazione precisa di sequenze di DNA esogene negli organoidi umani è priva di approcci di inserzione robusti ", hanno scritto gli autori.

Alcuni anni fa, i ricercatori hanno scoperto che CRISPR-Cas9, che agisce come minuscole forbici molecolari, può tagliare con precisione in un punto specifico del DNA. Questa nuova tecnologia ha notevolmente aiutato e semplificato l'ingegneria genetica.

"La piccola ferita nel DNA può attivare due diversi meccanismi di riparazione nelle cellule, che possono essere entrambi utilizzati dai ricercatori per costringere le cellule a prendere una nuova parte di DNA, al posto della ferita", ha osservato l'autore dello studio Delilah Hendriks, PhD, ricercatore postdottorato presso l'Istituto Hubrecht.

Si pensava che un metodo, chiamato giunzione di estremità non omologa, commettesse errori frequenti e quindi fino ad ora non era spesso utilizzato per inserire nuovi pezzi di DNA. "Poiché alcuni lavori precedenti sui topi indicavano che nuovi pezzi di DNA possono essere inseriti tramite giunzioni terminali non omologhe, abbiamo deciso di testarlo su organoidi umani", ha osservato Benedetta Artegiani, PhD, ricercatrice post-dottorato presso l'Hubrecht Institute .

Il gruppo di ricerca ha quindi scoperto che l'inserimento di qualsiasi pezzo di DNA negli organoidi umani attraverso l'unione di estremità non omologhe è in realtà più efficiente e robusto dell'altro metodo utilizzato fino ad ora. Hanno chiamato il loro nuovo metodo CRISPR-HOT.

"La transgenesi organoide indipendente dall'omologia mediata da CRISPR-Cas9 (CRISPR-HOT), consente la generazione efficiente di organoidi umani inseriti che rappresentano diversi tessuti", hanno spiegato gli autori. "CRISPR-HOT evita la clonazione estesa e supera la riparazione diretta dall'omologia (HDR) nell'ottenere un'integrazione precisa di sequenze di DNA esogeno nei loci desiderati, senza la necessità di inattivare TP53 nelle cellule non trasformate, che era precedentemente utilizzato per aumentare l'inserimento mediato da HDR . CRISPR-HOT è stato utilizzato per contrassegnare in fluorescenza e visualizzare molecole strutturali subcellulari e per generare linee reporter per tipi di cellule intestinali rari. Un doppio reporter - in cui il fuso mitotico è stato etichettato da tubulina endogena etichettata e la membrana cellulare da E-caderina endogena - ha scoperto modalità di divisione degli epatociti umani.

Gli scienziati Hubrecht hanno quindi utilizzato CRISPR-HOT per inserire etichette fluorescenti nel DNA degli organoidi umani, in modo tale che queste etichette fluorescenti fossero attaccate a geni specifici che volevano studiare. In primo luogo, i ricercatori hanno contrassegnato tipi specifici di cellule molto rare nell'intestino: le cellule enteroendocrine. Queste cellule producono ormoni per regolare, ad esempio, i livelli di glucosio, l'assunzione di cibo e lo svuotamento dello stomaco. Poiché queste cellule sono così rare, sono difficili da studiare. Tuttavia, con CRISPR-HOT, i ricercatori hanno facilmente "dipinto" queste cellule in diversi colori, dopodiché le hanno facilmente identificate ed analizzate.

Successivamente, i ricercatori hanno dipinto organoidi derivati da uno specifico tipo di cellula del fegato, le cellule duttali biliari. Usando CRISPR-HOT hanno visualizzato le cheratine, proteine coinvolte nello scheletro delle cellule. Ora che hanno potuto esaminare queste cheratine in dettaglio ed ad alta risoluzione, i ricercatori hanno scoperto la loro organizzazione in modo ultra-strutturale. Queste cheratine cambiano anche espressione quando le cellule si specializzano o si differenziano. Pertanto, i ricercatori anticipano che CRISPR-HOT potrebbe essere utile per studiare il destino e la differenziazione delle cellule.

All'interno del fegato, ci sono molti epatociti che contengono due (o anche più) volte il DNA di una cellula normale. Non è chiaro come si formino queste cellule e se siano in grado di dividersi a causa di questa quantità anormale di DNA. Gli anziani contengono più di questi epatociti anormali, ma non è chiaro se siano correlati a malattie come il cancro. Artegiani e Hendriks hanno utilizzato CRISPR-HOT per etichettare componenti specifici del meccanismo di divisione cellulare negli organoidi epatocitari e hanno studiato il processo di divisione cellulare.

"Abbiamo visto che gli epatociti" normali "si dividono in modo molto ordinato, dividendosi sempre in due cellule figlie in una certa direzione", ha spiegato Artegiani.

Hendriks ha aggiunto che “abbiamo anche trovato diverse divisioni in cui si è formato un epatocita anormale. Per la prima volta, abbiamo visto come un epatocita "normale" si trasforma in uno anormale ".

Oltre a questi risultati, i ricercatori hanno studiato gli effetti di una mutazione spesso riscontrata nel cancro del fegato, nel gene TP53, sulla divisione cellulare anormale negli epatociti. Senza TP53 questi epatociti anormali si stavano dividendo molto più spesso. Questo potrebbe essere uno dei modi in cui TP53 contribuisce allo sviluppo del cancro. I ricercatori ritengono che CRISPR-HOT possa essere applicato a molti tipi di organoidi umani, per visualizzare qualsiasi gene o tipo di cellula e per studiare molte domande relative allo sviluppo e alle malattie.

Da:

https://www.genengnews.com/news/hot-crispr-tool-creates-fast-and-efficient-knock-ins/

Commenti

Posta un commento