Plasma iperimmune, a che punto siamo? / Hyperimmune plasma, where are we?

Plasma iperimmune, a che punto siamo? / Hyperimmune plasma, where are we?

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

Le stiamo provando tutte. Antivirali vecchi e nuovi, anticorpi monoclonali, trattamenti off-label, vaccini, con alterne fortune. E da un po’ alla lista di possibili terapie contro Covid-19 si è aggiunto anche il plasma iperimmune, ovvero la parte liquida del sangue prelevata da pazienti guariti e contenente anticorpi specifici contro Sars-Cov-2. In verità, le sperimentazioni della terapia con plasma iperimmune sono cominciate quasi subito dopo lo scoppio della pandemia, all’inizio di aprile, per lo più come trattamento d’emergenza (o compassionevole) su pazienti in cui altri approcci non avevano funzionato. È bene dirlo subito: a oggi, le evidenze dell’efficacia del plasma iperimmune sono estremamente scarse e poco incoraggianti. Anzi, a dire il vero, i dati raccolti finora sembrano purtroppo puntare nella direzione opposta.

Cos’è e come dovrebbe funzionare

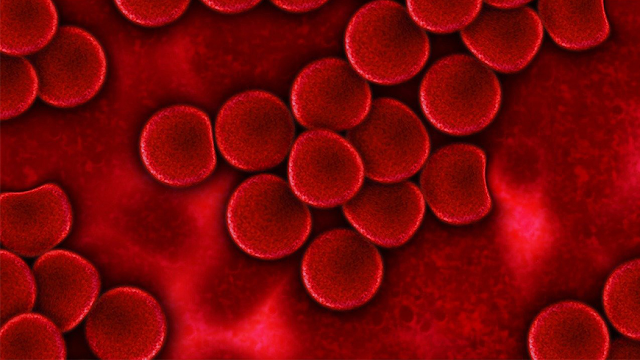

Il plasma è la parte liquida del sangue, di cui ne rappresenta circa il 55% (il resto sono globuli rossi, globuli bianchi e piastrine). È di colore giallo chiaro e composto per il circa 91% di acqua. Il razionale dietro l’infusione di plasma iperimmune è piuttosto semplice. Come spiegano gli esperti del Centro nazionale sangue all’Istituto superiore di sanità, si tratta di una terapia che prevede il prelievo da persone guarite da Covid-19 (in questo caso, naturalmente, ma il discorso potrebbe valere per qualsiasi malattia che genera una risposta immunitaria specifica) e la sua successiva somministrazione a pazienti affetti dalla stessa malattia. Prima dell’effettiva infusione, il plasma iperimmune viene sottoposto a una serie di test di laboratorio, anche per quantificare il livello di anticorpi neutralizzanti (la cosiddetta titolazione, che è un concetto molto importante: ci torneremo tra poco), ed a procedure che garantiscono la sicurezza del ricevente. L’idea è di trasferire gli anticorpi specifici sviluppati dai pazienti guariti a quelli con infezione in atto, che non ne abbiano ancora prodotti di propri. Si tratta, nella fattispecie, di immunoglobuline, proteine coinvolte nella risposta immunitaria prodotte dai linfociti B in risposta a un’infezione, che si legano all’agente patogeno e lo neutralizzano.

Ebola, Sars, influenza

Come già accennato, Sars-Cov-2 non è il primo virus contro il quale è stato tentato quest’approccio. Uno dei primi casi risale addirittura all’epidemia di influenza spagnola del 1918; poi, nel corso degli anni, è stato somministrato (sempre in regime di terapia compassionevole o di sperimentazione clinica), a pazienti colpiti da epatite B, rabbia, tetano, varicella, Sars (la prima), ebola, influenza. In tutti questi casi, però, i risultati delle somministrazioni non sono stati ritenuti abbastanza solidi o conclusivi rispetto all’efficacia del trattamento. Per questo, in generale, la comunità scientifica tende a considerare il plasma iperimmune tutt’al più come un ponte in attesa di terapie efficaci o di un vaccino.

“Storicamente, il plasma dei convalescenti”, ha spiegato al New York Times Erin Goodhue, dirigente della Croce Rossa statunitense, “è stato usato come profilassi e come terapia soprattutto in periodi di arrivo di nuove malattie, sia virali che batteriche, quando ancora non si hanno a disposizione terapie mirate e specifiche contro questi patogeni”. Nel caso di Covid, come avvenuto per tutti gli altri trattamenti, gli sforzi e le speranze si sono decuplicati: “Ciò che mi colpisce particolarmente”, dice ancora Goodhue, “è che finora non si era mai usato così tanto il plasma iperimmune: vuol dire che, per la prima volta, la comunità scientifica avrà la possibilità di condurre studi rigorosi sulla procedura che potranno valutarne più precisamente l’efficacia. Negli usi precedenti del trattamento non era stato possibile condurre questo tipo di studi”. Il plasma iperimmune, tra l’altro, è stato anche sperimentato su disturbi non virali, come ustioni, traumi e perfino cancro. Ma i risultati sono sempre gli stessi: non ci sono prove solide sulla sua efficacia.

Cos’è successo negli ultimi mesi

In un lungo articolo, Valigia Blu ha messo insieme e ricostruito le notizie sull’uso del plasma iperimmune contro Covid-19 da quando è scoppiata la pandemia. Il primo utilizzo risale al febbraio scorso, quando il China National Biotech Group, un’azienda privata cinese, informò di aver eseguito il trattamento su più di dieci pazienti, ottenendo miglioramenti in 24 ore. Poco più di un mese dopo, anche in Italia fu avviato il primo protocollo di sperimentazione del plasma iperimmune, condotta dall’Asst di Mantova e dal Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia. E poi gli Stati Uniti, dove il 25 marzo la Food and Drug Administration fornì precise raccomandazioni nel caso le strutture sanitarie volessero avviare la terapia per uso compassionevole (Nature scrisse che gli ospedali di New York si stavano preparando a usare questa “antica terapia” per ridurre la pressione sulle terapie intensive). Seguirono anche Germania, Regno Unito, Spagna, Iran, Corea del sud e India.

“Nessuna prova di efficacia”

Eccoci al presente, che avevamo già anticipato. I risultati delle sperimentazioni condotte finora sembrano confermare al momento non è possibile stabilire se il plasma sia una terapia efficace. Gli autori di una meta-analisi di Cochrane, per esempio, che ha preso in esame i dati di 19 studi per un totale di quasi 40mila partecipanti, hanno scritto di “essere incerti sul fatto che il plasma di persone guarite da Covid-19 sia un trattamento efficace, e anche sul fatto che possa avere effetti collaterali”. Più trancianti i risultati di uno studio indiano pubblicato sul British Medical Journal e di un altro, recentissimo, pubblicato sul New England Journal of Medicine, che non ha rilevato vantaggi significativi nella somministrazione di plasma iperimmune.

Tutto da dimenticare, allora? Sì e no. Abbiamo chiesto qualche spiegazione in più a Francesco Menichetti, docente di malattie infettive all’Università di Pisa e soprattutto coordinatore di Tsunami, uno studio italiano che ha proprio l’obiettivo di testare l’efficacia del plasma iperimmune: “Il lavoro appena pubblicato sul New England Journal of Medicine suggerisce che il plasma iperimmune sia inefficace”, ammette. “Prendiamo atto di questo risultato: si tratta di un lavoro serio e condotto con ottimo rigore metodologico. C’è però qualche pecca tecnica relativa alla titolazione del plasma utilizzato, che è stata verificata solo nel 56% dei casi trattati e che è stata condotta con un metodo che potrebbe farlo apparire più ricco di anticorpi di quanto non lo sia realmente. In ogni caso, lo studio attesta che il plasma iperimmune non apporta benefici ma neanche – fortunatamente – effetti collaterali”.

I limiti tecnici dello studio argentino potrebbero essere presto fugati dai risultati italiani, dice ancora Menichetti: “Nel nostro studio stiamo utilizzando un plasma titolato ad alto livello. Abbiamo arruolato oltre 380 pazienti ed in questi giorni un organismo indipendente sta conducendo un’analisi preliminare sui nostri dati. Contiamo che nel giro di qualche settimana potremo avere i primi risultati”. Menichetti, con grande onestà, riconosce che al momento è necessaria “la massima cautela e prudenza” rispetto a questa terapia e soprattutto ne sconsiglia l’uso perfino come terapia compassionevole: “Date le evidenze attuali, ritengo che il plasma iperimmune debba essere usato soltanto all’interno di studi clinici, in sperimentazioni controllate”. E conclude con un appello a continuare a donarlo, perché le sacche cominciano a scarseggiare. E gli esperimenti devono andare avanti.

ENGLISH

We are trying them all. Old and new antivirals, monoclonal antibodies, off-label treatments, vaccines, with mixed success. And for some time now hyperimmune plasma has also been added to the list of possible therapies against Covid-19, i.e. the liquid part of the blood taken from recovered patients and containing specific antibodies against Sars-Cov-2. In truth, trials of hyperimmune plasma therapy began almost immediately after the outbreak of the pandemic, in early April, mostly as an emergency (or compassionate) treatment on patients in whom other approaches had not worked. It is good to say it immediately: to date, the evidence of the efficacy of hyperimmune plasma is extremely scarce and not very encouraging. Indeed, to tell the truth, the data collected so far seem unfortunately to point in the opposite direction.

What it is and how it should work

Plasma is the liquid part of blood, of which it accounts for about 55% (the rest are red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets). It is light yellow in color and composed of approximately 91% water. The rationale behind hyperimmune plasma infusion is quite simple. As the experts of the National Blood Center at the Higher Institute of Health explain, it is a therapy that involves the collection from people healed from Covid-19 (in this case, of course, but the speech could be valid for any disease that generates a response specific immune system) and its subsequent administration to patients with the same disease. Before the actual infusion, the hyperimmune plasma is subjected to a series of laboratory tests, also to quantify the level of neutralizing antibodies (the so-called titration, which is a very important concept: we will return to it shortly), and to procedures that guarantee the recipient safety. The idea is to transfer the specific antibodies developed by healed patients to those with active infection, who have not yet produced any of their own. In this case, these are immunoglobulins, proteins involved in the immune response produced by B lymphocytes in response to an infection, which bind to the pathogen and neutralize it.

Ebola, SARS, flu

As already mentioned, Sars-Cov-2 is not the first virus against which this approach has been attempted. One of the first cases even dates back to the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918; then, over the years, it was administered (always in compassionate therapy or clinical trials) to patients affected by hepatitis B, rabies, tetanus, chicken pox, SARS (the first), ebola, flu. In all these cases, however, the results of the administrations were not deemed solid or conclusive enough with respect to the effectiveness of the treatment. For this reason, in general, the scientific community tends to consider hyperimmune plasma at most as a bridge waiting for effective therapies or a vaccine.

"Historically, the plasma of convalescents", Erin Goodhue, executive of the US Red Cross explained to the New York Times, "has been used as a prophylaxis and as a therapy especially in periods of arrival of new diseases, both viral and bacterial, when not yet targeted and specific therapies are available against these pathogens ". In the case of Covid, as happened for all other treatments, efforts and hopes have increased tenfold: "What strikes me particularly", says Goodhue, "is that up to now, hyperimmune plasma has never been used so much: it wants to say that, for the first time, the scientific community will have the opportunity to conduct rigorous studies on the procedure that will be able to evaluate its effectiveness more precisely. In previous uses of the treatment it was not possible to conduct this type of study ”. Hyperimmune plasma, among other things, has also been tested on non-viral disorders, such as burns, trauma and even cancer. But the results are always the same: there is no solid evidence for its effectiveness.

What has happened in recent months

In a long article, Blue Suitcase has compiled and reconstructed the news on the use of hyperimmune plasma against Covid-19 since the pandemic broke out. The first use dates back to last February, when the China National Biotech Group, a Chinese private company, reported that it had performed the treatment on more than ten patients, obtaining improvements in 24 hours. A little more than a month later, the first hyperimmune plasma experimentation protocol was launched in Italy too, conducted by the Asst of Mantua and the Policlinico San Matteo of Pavia. And then the United States, where on March 25 the Food and Drug Administration gave precise recommendations in case health facilities wanted to initiate compassionate use therapy (Nature wrote that New York hospitals were preparing to use this "ancient therapy" for reduce the pressure on intensive care). Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain, Iran, South Korea and India also followed.

"No proof of efficacy"

Here we are at the present, which we had already anticipated. The results of the experiments conducted so far seem to confirm at the moment it is not possible to establish whether plasma is an effective therapy. The authors of a Cochrane meta-analysis, for example, which examined data from 19 studies totaling nearly 40,000 participants, wrote that "they are unsure whether the plasma of people recovered from Covid-19 is an effective treatment, and also on the fact that it can have side effects ". The results of an Indian study published in the British Medical Journal and another, very recent, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, which found no significant advantages in the administration of hyperimmune plasma, are more cutting.

Everything to forget, then? Yes and no. We asked Francesco Menichetti, professor of infectious diseases at the University of Pisa and above all coordinator of Tsunami, an Italian study that aims to test the efficacy of hyperimmune plasma: "The work just published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests hyperimmune plasma is ineffective, ”he admits. “We take note of this result: it is a serious work conducted with excellent methodological rigor. However, there is some technical flaw relating to the titration of the plasma used, which was verified only in 56% of the cases treated and which was conducted with a method that could make it appear richer in antibodies than it really is. In any case, the study attests that hyperimmune plasma does not bring benefits but neither - fortunately - side effects ”.

The technical limitations of the Argentine study could soon be dispelled by the Italian results, says Menichetti: “In our study we are using a high-level titrated plasma. We have enrolled over 380 patients and in these days an independent body is conducting a preliminary analysis on our data. We hope that in a few weeks we will be able to have the first results ”. Menichetti, with great honesty, acknowledges that at the moment "the utmost caution and prudence" is necessary with respect to this therapy and above all he does not recommend its use even as a compassionate therapy: "Given the current evidence, I believe that hyperimmune plasma should only be used within clinical trials, in controlled trials ". And he concludes with an appeal to continue donating it, because the bags are starting to run out. And the experiments must go on.

Da:

https://www.wired.it/scienza/medicina/2020/11/28/plasma-iperimmune-punto/?utm_source=news&utm_campaign=daily&utm_brand=wi&utm_mailing=WI_NEWS_Daily%202020-11-28&utm_medium=email&utm_term=WI_NEWS_Daily

Commenti

Posta un commento