Evoluzione anticorpale / Antibody Evolution

Evoluzione anticorpale / Antibody Evolution

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

Quando batteri o virus dannosi entrano nel corpo, le cellule immunitarie individuano proteine rivelatrici note come antigeni sulla superficie degli invasori e inviano eserciti di anticorpi per respingerli. Se alcuni di questi anticorpi hanno la forma giusta, possono agganciarsi e bloccare gli antigeni come la chiave di un lucchetto.

Ma il nostro sistema immunitario non ha sempre gli anticorpi giusti per combattere un particolare invasore. Così negli ultimi decenni gli scienziati hanno imparato a lavorare con animali come cammelli e lama ed as utilizzare tecniche di progettazione sintetica in laboratorio, per generare anticorpi che possono essere trasformati in medicinali.

Ad oggi, la FDA ha approvato più di 85 terapie anticorpali, tra cui a due concesse l'autorizzazione di emergenza per il trattamento del COVID-19.

Nonostante il loro successo, gli approcci attuali presentano degli svantaggi. Nel tentativo di superare questi ostacoli, i ricercatori della Harvard Medical School e dell'Università della California, Irvine, hanno sviluppato una tecnologia adattiva più rapida, semplice ed economica per generare anticorpi altamente specializzati.

Hanno già utilizzato la piattaforma, soprannominata AHEAD, per sviluppare anticorpi contro il virus che causa il COVID-19. Altri gruppi stanno ora studiando quegli anticorpi come base per test diagnostici e terapie.

"Riteniamo che AHEAD sarà un potente strumento per scoprire e ottimizzare rapidamente gli anticorpi, in particolare per affrontare i patogeni in rapida evoluzione", ha affermato Andrew Kruse, professore di chimica biologica e farmacologia molecolare presso l'Istituto Blavatnik di HMS e co-investigatore senior dello studio con Chang Liu all'Università di Irvine.

La scoperta più rapida di anticorpi potrebbe accelerare lo sviluppo di farmaci, i test diagnostici e gli esperimenti scientifici di base.

Come riportato il 24 giugno su Nature Chemical Biology , il metodo utilizza il lievito per produrre centinaia di milioni di diversi frammenti di anticorpi sintetici chiamati nanocorpi. I ricercatori possono rilasciare il loro antigene di interesse, come la proteina spike che SARS-CoV-2 usa per entrare e infettare le cellule umane, in una fiala di lievito e vedere quali nanocorpi si attaccano.

Il team ha progettato il lievito in modo che i nanocorpi evolvano ad ogni generazione. Ciò consente ai ricercatori di prendere i vincitori del primo round, metterli in una nuova fiala e condurre un secondo tipo per ottenere nanocorpi che si agganciano all'antigene con ancora più successo. Possono eseguire ulteriori round finché non sono soddisfatti di avere uno o più nanocorpi che si legano bene, e si legano solo, all'antigene che causa la malattia, massimizzando la possibilità di sviluppare una terapia che sia efficace e abbia effetti collaterali minimi.

L'intero processo utilizza tecniche di coltura del lievito standard di laboratorio e richiede solo una settimana e mezza o tre. I ricercatori possono cercare nanocorpi contro molti antigeni diversi contemporaneamente.

"Possiamo sviluppare anticorpi a velocità e scala precedentemente inaccessibili", ha affermato Kruse. "È un nuovo modo di fare ingegneria proteica combinatoria."

AHEAD è l'abbreviazione di Autonomous Hypermutation yEast surface Display.

Il lavoro si basa su una precedente piattaforma guidata da Kruse e da un collega dell'Università della California, a San Francisco. La nuova versione si differenzia per le sue capacità di evoluzione autonoma, che imitano il modo in cui gli anticorpi si evolvono naturalmente nei lama e nei cammelli.

"È emozionante portare questo potente processo immunitario negli animali alle cellule di lievito", ha affermato Conor McMahon, co-primo autore dell'articolo con Alon Wellner nel laboratorio Liu. McMahon ha condotto il lavoro mentre era un borsista post-dottorato nel laboratorio Kruse. Ora è un Vertex Fellow presso Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

Potenziale pandemico

Mentre AHEAD ha il potenziale per produrre anticorpi contro minacce come tumori e proteine coinvolte in condizioni autoimmuni, Kruse e colleghi sono concentrati per il momento sull'utilizzo della tecnologia per combattere il COVID-19 .

"Volevamo portare avanti questo progetto il più velocemente possibile", ha detto Kruse, "e speriamo di poter agire ancora più rapidamente se qualcosa come questa pandemia dovesse accadere di nuovo".

Quando i ricercatori hanno introdotto gli antigeni SARS-CoV-2 nelle fiale di lievito, hanno scoperto nanocorpi che li hanno neutralizzati almeno e, in alcuni casi, meglio degli anticorpi esistenti generati da pazienti umani, animali ed esperimenti di laboratorio.

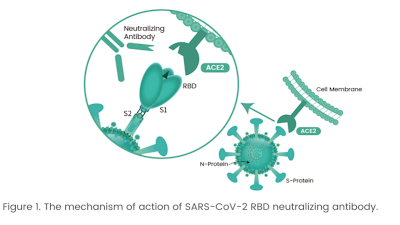

I nanocorpi hanno avuto un successo variabile nel convincere gli antigeni a legarsi a loro invece che al recettore ACE2, che SARS-CoV-2 utilizza per entrare nelle cellule umane.

Alcuni colleghi che sono andati avanti con i candidati nanobody più promettenti hanno iniziato a vedere risultati simili nei modelli animali, mentre altri stanno usando i nanobody per cercare di sviluppare strumenti migliori per rilevare SARS-CoV-2 e coronavirus correlati, secondo Kruse e co- autori.

AHEAD potrebbe anche aiutare gli esperti a rispondere più velocemente quando sorgono nuove varianti di SARS-CoV-2 o agenti patogeni completamente nuovi.

"Se SARS-CoV-2 si evolve in un modo che sfugge alle attuali terapie anticorpali di emergenza, dovremmo essere in grado di svilupparne di nuovi in circa due settimane per bloccare le varianti di fuga", ha affermato Kruse.

Poiché "quasi tutti i laboratori di biologia" sono attrezzati per utilizzare le semplici attrezzature e tecniche, AHEAD dovrebbe consentire a molti gruppi di lavorare per trovare soluzioni a future epidemie "in una risposta distribuita che soddisfi l'urgenza del problema", ha aggiunto Kruse.

ENGLISH

New tool aims to fight COVID-19, other diseases.

When harmful bacteria or viruses enter the body, immune cells spot telltale proteins known as antigens on the invaders’ surfaces and send out armies of antibodies to fend them off. If some of those antibodies have just the right shape, they can latch onto and block the antigens like the key to a padlock.

But our immune systems don’t always have the right antibodies to fight a particular invader. So over the past few decades scientists learned to work with animals such as camels and llamas, and to use synthetic design techniques in the lab, to generate antibodies that can be turned into medicines.

More than 85 antibody therapies have been approved by the FDA to date, including two granted emergency authorization for treating COVID-19.

Despite their success, current approaches have drawbacks. In an effort to leap these hurdles, researchers at Harvard Medical School and the University of California, Irvine, have developed a swifter, simpler, and cheaper adaptive technology to generate highly specialized antibodies.

They have already used the platform, dubbed AHEAD, to evolve antibodies against the virus that causes COVID-19. Other groups are now investigating those antibodies as the basis for diagnostic tests and therapies.

“We believe AHEAD will be a powerful tool for quickly discovering and optimizing antibodies, especially for addressing rapidly evolving pathogens,” said Andrew Kruse, professor of biological chemistry and molecular pharmacology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and co-senior investigator of the study with Chang Liu at UC Irvine.

Faster antibody discovery could accelerate drug development, diagnostic testing, and basic science experiments.

As reported June 24 in Nature Chemical Biology, the method uses yeast to make hundreds of millions of different synthetic antibody fragments called nanobodies. Researchers can drop their antigen of interest—such as the spike protein that SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter and infect human cells—into a vial of the yeast and see which nanobodies latch on.

The team engineered the yeast so that the nanobodies evolve with each generation. That allows researchers to take the first-round winners, put them in a new vial, and conduct a second sort to get nanobodies that lock onto the antigen even more successfully. They can run additional rounds until they’re satisfied that they have one or more nanobodies that bind well, and bind only, to the disease-causing antigen, maximizing the chance of developing a therapy that is effective and has minimal side effects.

The whole process uses standard laboratory yeast culture techniques and takes just one and a half to three weeks. Researchers can hunt for nanobodies against many different antigens at the same time.

“We can evolve antibodies at previously inaccessible speed and scale,” said Kruse. “It’s a new way of doing combinatorial protein engineering.”

AHEAD is short for Autonomous Hypermutation yEast surfAce Display.

The work builds on an earlier platform led by Kruse and a colleague at the University of California, San Francisco. The new version differs in its autonomous evolution abilities, which mimic the way antibodies naturally evolve in llamas and camels.

“It’s exciting to bring this powerful immune process in animals to yeast cells,” said Conor McMahon, co-first author of the paper with Alon Wellner in the Liu lab. McMahon conducted the work while a postdoctoral fellow in the Kruse lab. He is now a Vertex Fellow at Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

Pandemic potential

While AHEAD has the potential to produce antibodies against threats such as cancers and proteins involved in autoimmune conditions, Kruse and colleagues are focused for the moment on using the technology to combat COVID-19.

“We wanted to get this project going as fast as we could,” said Kruse, “and we’re hoping we can now act even more quickly should something like this pandemic happen again.”

When the researchers introduced SARS-CoV-2 antigens into the yeast vials, they uncovered nanobodies that neutralized them at least as well as, and in some cases better than, existing antibodies generated from human patients, animals, and lab experiments.

The nanobodies had varying success in convincing the antigens to bind to them instead of to the ACE2 receptor, which SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter human cells.

Some colleagues who moved forward with the most promising nanobody candidates have begun to see similar results in animal models, while others are using the nanobodies to try to develop better tools to detect SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses, according to Kruse and co-authors.

AHEAD could also help experts respond faster when new SARS-CoV-2 variants or entirely new pathogens arise.

“If SARS-CoV-2 evolves in a way that escapes current emergency-use antibody therapies, we should be able to evolve new ones in about two weeks to block the escape variants,” said Kruse.

Since “almost any biology lab” is equipped to use the simple equipment and techniques, AHEAD should empower many groups to work on finding solutions to future outbreaks “in a distributed response that meets the urgency of the problem,” Kruse added.

Da:

https://hms.harvard.edu/news/antibody-evolution?utm_source=Silverpop&utm_medium=email&utm_term=field_news_item_1&utm_content=HMNews06282021

Commenti

Posta un commento