Scienziati deviano un fulmine sparando un laser nel cielo / Scientists deflect lightning by shooting a laser into the sky

Scienziati deviano un fulmine sparando un laser nel cielo / Scientists deflect lightning by shooting a laser into the sky

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

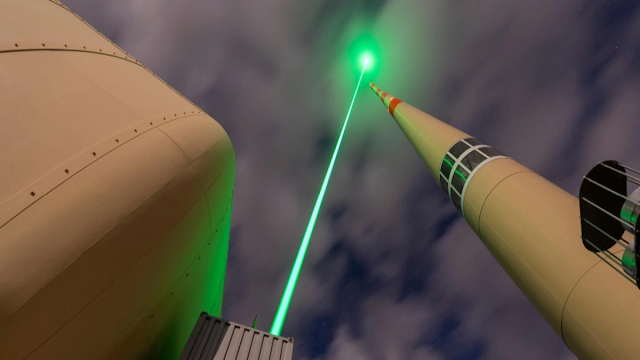

Un gruppo di scienziati che ha sperimentato i

laser in cima a una montagna svizzera dove si

erge una grande torre di telecomunicazioni in

metallo.

Il fisico Aurélien Houard, del Laboratorio di ottica

applicata del Centro nazionale francese per la

ricerca scientifica a Parigi, e colleghi hanno

resistito a ore di attività temporalesca per verificare

se un laser potesse allontanare i fulmini dalle

infrastrutture critiche. La torre delle

telecomunicazioni viene colpita da un fulmine

circa 100 volte all’anno. È simile al numero di

lampi che colpiscono il pianeta Terra o

scoppiettano tra le nuvole ogni secondo.

Collettivamente, questi attacchi possono causare

danni per miliardi di dollari ad aeroporti e rampe di

lancio, per non parlare delle persone. La nostra

migliore protezione contro i fulmini è una verga di

Franklin , nient’altro che una guglia di metallo

inventata nel 18 ° secolo da Benjamin Franklin,

che scoprì che i fulmini sono fulmini elettrici a zig-

zag . Quelle aste si collegano a cavi metallici che

corrono giù dagli edifici e si ancorano alla Terra,

lavorando per dissipare l’energia dei fulmini.

Houard e colleghi volevano escogitare un modo

migliore per proteggersi dai fulmini, combattendo

l’elettricità con la luce. “Sebbene questo campo di

ricerca sia stato molto attivo per più di 20 anni,

questo è il primo risultato sul campo che dimostra

sperimentalmente un fulmine guidato dai laser”

, scrivono nel loro articolo pubblicato. Con un

aumento degli eventi meteorologici estremi guidati

dai cambiamenti climatici sul radar, la protezione

dai fulmini sta diventando sempre più importante.

La campagna sperimentale si è svolta nell’estate

del 2021 dal Säntis nella Svizzera nordorientale.

Brevi e intensi impulsi laser sono stati lanciati

nelle nuvole durante una serie di temporali e hanno

deviato con successo quattro scariche di fulmini

verso l’alto lontano dalla punta della torre. Altri 12

fulmini hanno colpito la torre durante quei periodi

di temporale in cui il laser era inattivo. In

un’occasione, quando il cielo era sufficientemente

limpido per catturare l’azione su due telecamere ad

alta velocità separate, è stato registrato un fulmine

che seguiva il percorso del laser per 50 metri (164

piedi). I sensori sulla torre delle telecomunicazioni

hanno anche registrato i campi elettrici ed i raggi X

generati per rilevare l’attività dei fulmini e

confermarne il percorso. Mentre i ricercatori

stanno ancora cercando di capire perché i laser

hanno funzionato nelle loro prove ma non negli

esperimenti precedenti, hanno alcune idee. Il laser

Houard e colleghi hanno utilizzato fuochi fino a

mille impulsi al secondo, molto più veloci di altri

laser utilizzati, consentendo al raggio verde di

intercettare tutti i precursori di fulmini che si

formano sopra la torre. Ma gli eventi laser

registrati sembravano solo deviare i lampi positivi,

che sono prodotti da una nuvola caricata

positivamente e generano “leader” verso l’alto

caricati negativamente. Come spiegano Houard e

colleghi nel loro articolo, il laser inviato verso il

cielo modifica le proprietà di flessione della luce

dell’aria, facendo restringere e intensificare

l’impulso laser fino a quando non inizia a ionizzare

le molecole d’aria.

Questo processo è chiamato filamentazione . Le

molecole d’aria vengono rapidamente riscaldate

lungo il percorso del laser, assorbendone l’energia

, quindi espulse a velocità supersonica. Questo

lascia dietro di sé canali “di lunga durata” di aria

meno densa che offrono un percorso per le scariche

elettriche. “Ad alti tassi di ripetizione del laser,

queste molecole di ossigeno cariche di lunga

durata si accumulano, mantenendo una memoria

del percorso del laser” per il fulmine da seguire,

scrivono i ricercatori. Scariche elettriche lunghe

metri erano state guidate dai laser in laboratorio

, ma questa è la prima volta che la tecnica ha

funzionato durante un temporale. Le condizioni del

laser sono state regolate in modo che l’inizio del

comportamento filamentoso iniziasse appena sopra

la punta della torre. “Questo lavoro apre la strada a

nuove applicazioni atmosferiche di laser ultracorti

e rappresenta un importante passo avanti nello

sviluppo di una protezione dai fulmini basata su

laser per aeroporti, rampe di lancio o grandi

infrastrutture”, concludono Houard e colleghi.

ENGLISH

A group of scientists experimenting with lasers atop

a Swiss mountain where a large metal

telecommunications tower stands.

Physicist Aurélien Houard, of the French National

Center for Scientific Research's Applied Optics

Laboratory in Paris, and colleagues weathered

hours of thunderstorm activity to test whether a

laser could ward off lightning strikes from critical

infrastructure. The telecommunications tower is

struck by lightning about 100 times a year. It's

similar to the number of lightning bolts that strike

planet Earth or crackle through the clouds every

second. Collectively, these attacks can cause

billions of dollars in damage to airports and launch

pads, not to mention people. Our best lightning

protection is a Franklin rod, nothing more than a

metal spire invented in the 18th century by

Benjamin Franklin, who discovered that lightning

is a zigzagging pattern of electric lightning. Those

rods connect to metal cables that run down from

buildings and anchor to the Earth, working to

dissipate the lightning's energy. Houard and

colleagues wanted to come up with a better way to

protect themselves from lightning by fighting the

electricity with light. “Although this research field

has been very active for more than 20 years, this is

the first field result experimentally demonstrating

laser-guided lightning,” they write in their

published paper. With an increase in extreme

weather events driven by climate change on radar,

lightning protection is becoming increasingly

important. The test campaign took place in the

summer of 2021 from Säntis in northeastern

Switzerland. Short, intense laser pulses were fired

into the clouds during a series of thunderstorms

and successfully deflected four bolts of lightning

upwards away from the tower's tip. Another 12

lightning bolts struck the tower during those

thunderstorm periods when the laser was inactive.

On one occasion, when the sky was clear enough

to capture the action on two separate high-speed

cameras, lightning was recorded following the path

of the laser for 50 meters (164 feet). Sensors on the

telecommunications tower also recorded the

electric fields and X-rays generated to detect

lightning activity and confirm its path, which you

can see reconstructed in the video below. While the

researchers are still trying to figure out why the

lasers worked in their trials but not in previous

experiments, they have a few ideas. The laser

Houard and colleagues used fires of up to a

thousand pulses per second, much faster than other

lasers used, allowing the green beam to intercept

any lightning precursors that form above the tower.

But the recorded laser events only seemed to

deflect positive flashes, which are produced by a

positively charged cloud and generate upward

negatively charged "leaders." As Houard and

colleagues explain in their paper, the laser sent

skyward changes the light bending properties of

air, causing the laser pulse to narrow and intensify

until it begins to ionize air molecules.

This process is called filamentation. Air molecules

are rapidly heated in the path of the laser,

absorbing its energy, then ejected at supersonic

speed. This leaves behind "long-lasting" channels

of less dense air that provide a path for electrical

discharges. "At high laser repetition rates, these

long-lived charged oxygen molecules accumulate,

maintaining a memory of the laser's path" for the

lightning to follow, the researchers write. Meter

-long bolts of electricity had been guided by lasers

in the lab, but this is the first time the technique

has worked during a thunderstorm. The laser

conditions were adjusted so that the onset of

filamentary behavior began just above the tower

tip. “This work paves the way for new atmospheric

applications of ultrashort lasers and represents a

major breakthrough in the development of laser-

based lightning protection for airports, launch pads

or large infrastructure,” conclude Houard and

colleagues.

Da:

https://www.scienzenotizie.it/2023/01/16/scienziati-deviano-un-fulmine-sparando-un-laser-nel-cielo-3065043

Commenti

Posta un commento