Misterioso agente patogeno sta privando i ricci di mare della loro carne e trasformandoli in scheletri - e si sta diffondendo rapidamente / Mystery pathogen is stripping sea urchins of their flesh and turning them to skeletons — and it's spreading fast

Misterioso agente patogeno sta privando i ricci di mare della loro carne e trasformandoli in scheletri - e si sta diffondendo rapidamente / Mystery pathogen is stripping sea urchins of their flesh and turning them to skeletons — and it's spreading fast

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

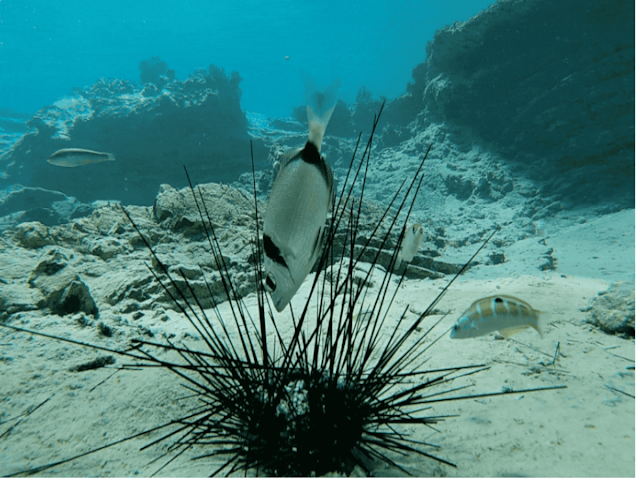

Pesce che becca un riccio di

mare morto nel Golfo di Aqaba. / Fish pecking at a dead sea urchin in the Gulf of Aqaba.

Pesce che becca un riccio di

mare morto nel Golfo di Aqaba. / Fish pecking at a dead sea urchin in the Gulf of Aqaba.Un'epidemia improvvisa e mortale che si è abbattuta sul Mar Rosso ha ucciso un'intera specie di ricci di mare, strappandone la carne e trasformandoli in scheletri.

Solo due mesi fa, migliaia di ricci di mare neri ( Diadema setosum ) vivevano nel Golfo di Aqaba, nella punta settentrionale del Mar Rosso, mantenendo sani i coralli facendo spuntini con le alghe in eccesso. Ora rimangono solo i loro scheletri, dopo che i loro tessuti sono stati consumati da un misterioso agente patogeno.

"È una morte rapida e violenta: in soli due giorni un riccio di mare sano diventa uno scheletro con una massiccia perdita di tessuto", ha detto in una nota Omri Bronstein , docente di zoologia all'Università di Tel Aviv . "Mentre alcuni cadaveri vengono portati a riva, la maggior parte dei ricci di mare viene divorata mentre sta morendo e non è in grado di difendersi, il che potrebbe accelerare il contagio da parte dei pesci che li predano".

I ricercatori hanno individuato i primi segni della peste dei ricci nel Mar Mediterraneo all'inizio dell'anno, quando una specie invasiva di ricci ha iniziato ad ammalarsi nelle acque intorno alla Grecia ed alla Turchia. Da lì, la malattia sembra essersi diffusa verso sud attraverso il Canale di Suez fino al Mar Rosso.

Gli scienziati non sono sicuri dell'esatta malattia che ha causato la moria di massa, ma sospettano che si tratti di un parassita ciliato patogeno - un microrganismo unicellulare - che nel 1983 ha eliminato l'intera popolazione di ricci di mare dei Caraibi. Prima della piaga dei parassiti, i Caraibi ospitavano rigogliose barriere coralline tropicali, ma da quando hanno perso i ricci di mare le barriere coralline sono state soffocate da fioriture algali che si sono moltiplicate senza controllo, bloccando la luce solare e distruggendo circa il 90% dei coralli della regione.

La malattia è stata identificata solo dopo che una seconda ondata ha colpito i Caraibi nel 2022, un evento che ha dato agli scienziati una seconda opportunità per studiarla.

"I ricci di mare sono i 'giardinieri' della barriera corallina: si nutrono delle alghe e impediscono loro di prendere il sopravvento e soffocare i coralli che competono con loro per la luce del sole", ha detto Bronstein. "Sfortunatamente, questi ricci di mare non esistono più nel Golfo di Eilat [Aqaba] e stanno rapidamente scomparendo dalle parti in continua espansione del Mar Rosso più a sud".

Il pericolo dei coralli della regione è significativo sia a livello locale che globale. Il Golfo di Aqaba è noto per i suoi numerosi punti di immersione ed è una popolare destinazione turistica. E poiché i coralli si sono evoluti a temperature e salinità elevate nel corso di milioni di anni, sono più resistenti alle fluttuazioni di temperatura guidate dai cambiamenti climatici che stanno uccidendo altre barriere coralline in tutto il mondo.

"Bisogna capire che la minaccia per le barriere coralline è già ai massimi storici, e ora è stata aggiunta una variabile precedentemente sconosciuta", ha detto Bronstein. "Questa situazione non ha precedenti nell'intera storia documentata del Golfo di Eilat [Aqaba]".

Bronstein afferma che per impedire l'eradicazione dell'intera popolazione di ricci di mare del Mar Rosso e del Mediterraneo, è necessaria un'azione urgente per stabilire popolazioni di riproduttori non infetti dei ricci in modo che possano essere restituiti agli oceani una volta terminata l'epidemia.

"Dobbiamo capire la gravità della situazione: nel Mar Rosso, la mortalità si sta diffondendo ad un ritmo incredibile e comprende già un'area molto più ampia di quella che vediamo nel Mediterraneo", ha detto Bronstein. "Sullo sfondo c'è ancora una grande incognita: cosa sta effettivamente uccidendo i ricci di mare? È l'agente patogeno dei Caraibi o qualche nuovo fattore sconosciuto?"

"In ogni caso, questo agente patogeno è chiaramente trasportato dall'acqua e prevediamo che in breve tempo l'intera popolazione di questi ricci di mare, sia nel Mediterraneo che nel Mar Rosso, si ammalerà e morirà", ha aggiunto Bronstein.

ENGLISH

A mysterious epidemic that began in the Mediterranean at the start of the year looks set to wipe out all of the Mediterranean and Red Sea’s urchins, and possibly their coral reefs too.

A sudden and deadly epidemic sweeping across the Red Sea has killed an entire species of sea urchin, stripping their flesh and turning them into skeletons.

Just two months ago, thousands of black sea urchins (Diadema setosum) lived in the Gulf of Aqaba, in the northern tip of the Red Sea, keeping the corals there healthy by snacking on excess algae. Now, only their skeletons remain, after their tissue was consumed by a mysterious pathogen.

"It's a fast and violent death: within just two days a healthy sea urchin becomes a skeleton with massive tissue loss," Omri Bronstein, a senior lecturer in Zoology at Tel Aviv University, said in a statement. "While some corpses are washed ashore, most sea urchins are devoured while they are dying and unable to defend themselves, which could speed up contagion by the fish who prey on them."

Researchers spotted the first signs of the urchin plague in the Mediterranean Sea at the beginning of the year, when an invasive species of urchin began falling sick in waters around Greece and Turkey. From there, the disease appears to have spread southward through the Suez Canal to the Red Sea.

Scientists are unsure of the exact disease causing the mass die-off, but they suspect it is a pathogenic ciliate parasite — a single-celled microorganism — which in 1983 eliminated the Caribbean’s entire sea urchin population. Before the parasite plague, the Caribbean was home to thriving tropical reefs, but since losing the sea urchins the reefs have been smothered by algal blooms that multiplied unchecked, blocking out sunlight and destroying around 90% of the region’s coral.

The disease was only identified after a second wave hit the Caribbean in 2022, an event which gave scientists a second opportunity to study it.

"The sea urchins are the reef's 'gardeners' — they feed on the algae and prevent them from taking over and suffocating the corals that compete with them for sunlight," Bronstein said. "Unfortunately, these sea urchins no longer exist in the Gulf of Eilat [Aqaba] and are quickly disappearing from constantly expanding parts of the Red Sea further south."

The imperilment of the region’s corals is significant on both a local and global level. The Gulf of Aqaba is known for its numerous diving spots and is a popular tourist destination. And because the corals there evolved to high temperatures and salinity over millions of years, they are more resistant to climate change-driven temperature fluctuations that are killing off other coral reefs around the world.

"It must be understood that the threat to coral reefs is already at an all-time peak, and now a previously unknown variable has been added," Bronstein said. "This situation is unprecedented in the entire documented history of the Gulf of Eilat [Aqaba]."

Bronstein says that to prevent the entire sea urchin populations of the Red Sea and the Mediterranean from being eradicated, urgent action is needed to establish uninfected broodstock populations of the urchins so that they can be returned to the oceans once the epidemic is over.

"We must understand the seriousness of the situation: in the Red Sea, mortality is spreading at a stunning rate, and already encompasses a much larger area than we see in the Mediterranean," Bronstein said. "In the background there is still a great unknown: What is actually killing the sea urchins? Is it the Caribbean pathogen or some new unfamiliar factor?"

"Either way, this pathogen is clearly carried by water, and we predict that in just a short time, the entire population of these sea urchins, in both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, will get sick and die," Bronstein added.

Da:

https://www.livescience.com/animals/mystery-pathogen-is-stripping-sea-urchins-of-their-flesh-and-turning-them-to-skeletons-and-its-spreading-fast?utm_term=0D44E3E5-72C8-4F2E-A2B4-93C82DC78FB4&utm_campaign=368B3745-DDE0-4A69-A2E8-62503D85375D&utm_medium=email&utm_content=2B4F47C4-6158-4C83-BD59-46E8E9227B24&utm_source=SmartBrief

Commenti

Posta un commento